but hey! dig this: We must love one another or die.

Up, Down, Appendices.

I watched Stanley Kubrick's unforgettable 1964 classic Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb again this week, and it has just dawned on me why he might have been called 'Strangelove' :-)

I watched Stanley Kubrick's unforgettable 1964 classic Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb again this week, and it has just dawned on me why he might have been called 'Strangelove' :-)I do enjoy imagining the plutocrats and otherwise powerful scurrying to prepare hidey-holes to jump into with buoyantly beautiful consorts when the time is right ... silly of course, Strangelove figgured on 93 years underground, but a changed climate is irrevocably changed ... so ...

but ok, here we go, let's get a good run at it with the Sex Pistols, No Future (God Save The Queen) on their albums Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's the Sex Pistols and Spunk, way back in 1977:

| god save the queen the fascist regime they made you a moron a potential h-bomb god save the queen she ain't no human being there is no future in england's dreaming don't be told what you want don't be told what you need. there's no future no future there's no future for you god save the queen we mean it man we love our queen god saves god save the queen 'cos tourists are money and our figurehead is not what she seems oh god save history god save your mad parade oh lord god have mercy all crimes are paid when there's no future how can there be sin we're the flowers in your dustbin we're the poison in your human machine we're the future your future god save the queen we mean it man we love our queen god saves god save the queen we mean it man there is no future in england's dreaming no future no future no future for you no fufure no future no future for me | Clive Hamilton says, "It seems to be a recipe for a kind of nihilism, like that glamourised in the Sex Pistol's song lamenting 'no future'," 'it' being 'decathexis' or Freud's way of saying 'letting go' or maybe 'mental dissipation' or maybe it was Freud's translator who said it, whatever, there have been two books this year (and the year is hardly past summer solstice), and in my estimation both of them are essential light-shedding mind-openers, they 'must be read' and so forth, but both of them are also ... 'Close but no cigar': (I really don't like to reference Amazon.com but since these books do not seem to be making it into the bookstores, and since when you order on-line from the publishers they seem to take forever, and since I have eventually and in a kind of desperation gotten my copies of both of them from Amazon.com ... well ... it's only fair eh?)  but here's something interesting - if you put 'em both together they actually get there, or as close as makes no difference to the cigars I go with. but here's something interesting - if you put 'em both together they actually get there, or as close as makes no difference to the cigars I go with.there are two other books which are also sort of, well ... essential, or you could say 'useful as background,' whatever: I put these two in the second rank because they both succumb to wishful thinking viz. that there is actually some kind of a 'solution,' this may be because both of these books were written a year or so earlier than McKibben's & Hamilton's and events are moving so quickly, and the science is moving so quickly, that despite having the courage to look just about straight up the delivery end of the shotgun for an extended period of time (which totally unnerves lesser people such as myself, leaveing them burnt & crazy) they just did not quite have the information yet ... I can't say. whatever their faults, Bill McKibben and Clive Hamilton are moving beyond mere (or maybe ephemeral or maybe illusory) solutions. |

the Sex Pistol's rant fails, not because it reflects enervation as our Clive opines, but because were it not for the big beautiful bountiful bourgeoisie with its universities, flawlessly skinned and smiling nubiles, and Jacuzzis, none of these authors would ever have shown up on the scene, so indeed, God save the bourgeoisie! God bless 'em all! God save the Queen! and ... I mean it man!

the Sex Pistol's rant fails, not because it reflects enervation as our Clive opines, but because were it not for the big beautiful bountiful bourgeoisie with its universities, flawlessly skinned and smiling nubiles, and Jacuzzis, none of these authors would ever have shown up on the scene, so indeed, God save the bourgeoisie! God bless 'em all! God save the Queen! and ... I mean it man!

(this young woman is a model from California someplace who calls herself L'Afua, and you can see her more-or-less naked and with her strength revealed at her blog if you like :-)

oh you know ... these triskelions, McKibben goes with, "lightly, carefully, gracefully," and Hamilton tries on, "Despair, Accept, Act," and I wonder if both of them are somehow subliminally reflecting Saint Paul and the old "Faith, Hope, and Charity" of the King James Version of the New Testament? Hamilton less so certainly, but part of what he means by 'Act' is to move towards civil disobedience ... and this does have a certain biblical ring to it, in my ears at least.

maybe it was Bertrand Russell who started talking about 'tendencies' or maybe I just remember that that's where I got the notion, and it is at least partly pernicious and probably very pernicious because it leads directly to the slippery slopes of gradualism and incrementalism that have undone our politicians, but here - I respectfully suggest that we go looking for counterforces rather than 'solutions'

counterforce comes to me from Thomas Punchon, both in The Crying of Lot 49 and his vision of Trystero and the knotted post-horn, and in Gravity's Rainbow where counterforce is an explicit theme, and from Charles Taylor in his The Malaise of Modernity when he tells us there will be neither ultimate victory nor ultimate defeat

and my memory is not what it used to be (and it was never very much), but it seems to me that Charles Taylor winds up with something sort of vaguely approximate towards the end of A Secular Age too, that there is no rational way out of the box we have built for ourselves, so we will have to break out or otherwise execute a very clever end-run, spiritually at least ... or die.

McKibben sets out with a (quite scientific) vision of out-of-control climate apocalypse, and being grounded in Methodism he is tricked by it (I surmise) into a considerable amount of nonsense, but arrives at community (the nexus & nub of counterforce as it were);

Hamilton, apparently very secular and (consequently?) very much clearer in the development of his ideas, starts with about the same (quite scientific & rational) vision (though he thankfully spends less space on it leaving room for some actual thought), and comes to revitalized democracy, which is very close indeed but unfortunately a little too dry;

and so we must combine them ... and anyway, we will not revitalize democracy without first undoing generations of secular atomism and re-establishing community, QED, that's it really ...

and so we must combine them ... and anyway, we will not revitalize democracy without first undoing generations of secular atomism and re-establishing community, QED, that's it really ...that, and Charles Taylor invoking Ivan Illich's vision of The Good Samaritan ... Charity eh? or as you might say, love.

because that is where you have to start, you have to start with the good Samaritan and love if you want to re-establish or re-constitute or re-generate or say, re-combooberate community, and a new democracy will follow that (and it must follow, as the night the day, or I never writ, nor no man ever loved).

because that is where you have to start, you have to start with the good Samaritan and love if you want to re-establish or re-constitute or re-generate or say, re-combooberate community, and a new democracy will follow that (and it must follow, as the night the day, or I never writ, nor no man ever loved).(I know I know, W.H Auden said this years ago, September 1, 1939, "We must love one another or die," and was apparently a bit embarrassed about it, oh well ...)

and okokokokok (!) maybe this shitty blog of mine is all about making principles out of my incapacities, and maybe it is all self-serving since I am the one who is alone, and for good reason no doubt though no one has made the effort or taken the time to explain as they let me go and walk away ... but it's not eh? and anyone who reads carefully knows this.

and a complete conception of community might make use of liminality and communitas from Victor Turner, The Ritual Process, Structure and Anti-Structure (see here)

far from understanding what this fence they have erected for the G20 really means (and it is not 'good fences make good neighbours'), they seem to have been permitted to prevent people from even taking pictures of it, ignoring the fundamental lessons of structures, that "rigidity attracts moments" and "you can't push a string" and failing to see this metaphor played out culturally, the war on terror, the war of every government on those they govern ...

and, yes, there was an earthquake in Toronto on Wednesday, and I felt it, and I knew exactly what it was (but not if and when it would stop :-)

and one of our CSIS security dogs, the mucky-muck poo-bah bureaucrat Richard Fadden, has begun to accuse some of our politicians of being foreign agents - does this not give you a clue? just look at the fear in his eyes ... and the anger and threat there too

and one of our CSIS security dogs, the mucky-muck poo-bah bureaucrat Richard Fadden, has begun to accuse some of our politicians of being foreign agents - does this not give you a clue? just look at the fear in his eyes ... and the anger and threat there tooa-and I have also been wondering about Paul Krugman for a while now, he's definitely smart enough but I have been looking for some rule-of-thumb to judge him with since I am no economist (nor do I want to be one, even if I were able) and I have come eventually to looking at what he might think about Growth ...

a fat lonely old white man with a soft spot for beautiful brown girls - is that it do you think?

a fat lonely old white man with a soft spot for beautiful brown girls - is that it do you think?I am afraid that I may have to go down and have a look at this fence of theirs myself ...

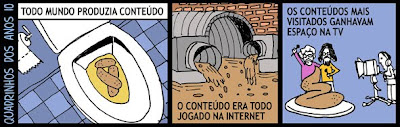

here's a cartoon for y'all,

Cartoons from the 10s

Everyone was producing content

The content was all thrown onto the Internet

The most visited content won space on TV

I saw these guys at the Fillmore East, must'a bin 1965 or so, it was Slum Goddess of the Lower East Side and I Get Horny (when I see you standing in your sable robe / and your breasts that launched a thousand round-pounds / you twirl through the light / your mons veneris / shines like Chichen Itza / in a jungle dawn) that grabbed our attention though at the time I had only a notion of what 'mons vereris' might be exactly :-)

interesting that Kupferberg was born in 1923, so he was 40 already, and Sanders was born in 1939 so mid-thirties ... pre-post-war sensibilities if you can say such a thing ... here they are in 1966 with Wide Wide River (of shit), and as old men in 2009 singing Dover Beach: Ah, love, let us be true to one another, for the world, which seems to lie before us like a land of dreams, so various, so beautiful, so new, hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light, nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain; and we are here as on a darkling plain swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, where ignorant armies clash by night. (Dover Beach)

a bit of the old 'Victorian Arch' structure in here eh? from the Sex Pistols' No Future to the Fugs' River of Shit; and a recapitulation of the scenario (or the conversion towards fullness) that moves from despair to community ... be well.

Appendices:

1. Building a Green Economy, Paul Krugman, April 5 2010.

2. Growth and Greenhouse Gases, Paul Krugman, April 13 2010.

3. Lies, Damned Lies, and Growth, Paul Krugman, May 24 2010.

4. Limits to growth and related stuff, Paul Krugman, April 22 2008.

See Paul Krugman's blog at NYT: The Conscience of a Liberal.

5. September 1, 1939, W.H. Auden.

6. Dover Beach, Matthew Arnold, 1867.

***************************************************************************

Building a Green Economy, Paul Krugman, April 5 2010.

If you listen to climate scientists — and despite the relentless campaign to discredit their work, you should — it is long past time to do something about emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. If we continue with business as usual, they say, we are facing a rise in global temperatures that will be little short of apocalyptic. And to avoid that apocalypse, we have to wean our economy from the use of fossil fuels, coal above all.

But is it possible to make drastic cuts in greenhouse-gas emissions without destroying our economy?

Like the debate over climate change itself, the debate over climate economics looks very different from the inside than it often does in popular media. The casual reader might have the impression that there are real doubts about whether emissions can be reduced without inflicting severe damage on the economy. In fact, once you filter out the noise generated by special-interest groups, you discover that there is widespread agreement among environmental economists that a market-based program to deal with the threat of climate change — one that limits carbon emissions by putting a price on them — can achieve large results at modest, though not trivial, cost. There is, however, much less agreement on how fast we should move, whether major conservation efforts should start almost immediately or be gradually increased over the course of many decades.

In what follows, I will offer a brief survey of the economics of climate change or, more precisely, the economics of lessening climate change. I’ll try to lay out the areas of broad agreement as well as those that remain in major dispute. First, though, a primer in the basic economics of environmental protection.

Environmental Econ 101

If there’s a single central insight in economics, it’s this: There are mutual gains from transactions between consenting adults. If the going price of widgets is $10 and I buy a widget, it must be because that widget is worth more than $10 to me. If you sell a widget at that price, it must be because it costs you less than $10 to make it. So buying and selling in the widget market works to the benefit of both buyers and sellers. More than that, some careful analysis shows that if there is effective competition in the widget market, so that the price ends up matching the number of widgets people want to buy to the number of widgets other people want to sell, the outcome is to maximize the total gains to producers and consumers. Free markets are “efficient” — which, in economics-speak as opposed to plain English, means that nobody can be made better off without making someone else worse off.

Now, efficiency isn’t everything. In particular, there is no reason to assume that free markets will deliver an outcome that we consider fair or just. So the case for market efficiency says nothing about whether we should have, say, some form of guaranteed health insurance, aid to the poor and so forth. But the logic of basic economics says that we should try to achieve social goals through “aftermarket” interventions. That is, we should let markets do their job, making efficient use of the nation’s resources, then utilize taxes and transfers to help those whom the market passes by.

But what if a deal between consenting adults imposes costs on people who are not part of the exchange? What if you manufacture a widget and I buy it, to our mutual benefit, but the process of producing that widget involves dumping toxic sludge into other people’s drinking water? When there are “negative externalities” — costs that economic actors impose on others without paying a price for their actions — any presumption that the market economy, left to its own devices, will do the right thing goes out the window. So what should we do? Environmental economics is all about answering that question.

One way to deal with negative externalities is to make rules that prohibit or at least limit behavior that imposes especially high costs on others. That’s what we did in the first major wave of environmental legislation in the early 1970s: cars were required to meet emission standards for the chemicals that cause smog, factories were required to limit the volume of effluent they dumped into waterways and so on. And this approach yielded results; America’s air and water became a lot cleaner in the decades that followed.

But while the direct regulation of activities that cause pollution makes sense in some cases, it is seriously defective in others, because it does not offer any scope for flexibility and creativity. Consider the biggest environmental issue of the 1980s — acid rain. Emissions of sulfur dioxide from power plants, it turned out, tend to combine with water downwind and produce flora- and wildlife-destroying sulfuric acid. In 1977, the government made its first stab at confronting the issue, recommending that all new coal-fired plants have scrubbers to remove sulfur dioxide from their emissions. Imposing a tough standard on all plants was problematic, because retrofitting some older plants would have been extremely expensive. By regulating only new plants, however, the government passed up the opportunity to achieve fairly cheap pollution control at plants that were, in fact, easy to retrofit. Short of a de facto federal takeover of the power industry, with federal officials issuing specific instructions to each plant, how was this conundrum to be resolved?

Enter Arthur Cecil Pigou, an early-20th-century British don, whose 1920 book, “The Economics of Welfare,” is generally regarded as the ur-text of environmental economics.

Somewhat surprisingly, given his current status as a godfather of economically sophisticated environmentalism, Pigou didn’t actually stress the problem of pollution. Rather than focusing on, say, London’s famous fog (actually acrid smog, caused by millions of coal fires), he opened his discussion with an example that must have seemed twee even in 1920, a hypothetical case in which “the game-preserving activities of one occupier involve the overrunning of a neighboring occupier’s land by rabbits.” But never mind. What Pigou enunciated was a principle: economic activities that impose unrequited costs on other people should not always be banned, but they should be discouraged. And the right way to curb an activity, in most cases, is to put a price on it. So Pigou proposed that people who generate negative externalities should have to pay a fee reflecting the costs they impose on others — what has come to be known as a Pigovian tax. The simplest version of a Pigovian tax is an effluent fee: anyone who dumps pollutants into a river, or emits them into the air, must pay a sum proportional to the amount dumped.

Pigou’s analysis lay mostly fallow for almost half a century, as economists spent their time grappling with issues that seemed more pressing, like the Great Depression. But with the rise of environmental regulation, economists dusted off Pigou and began pressing for a “market-based” approach that gives the private sector an incentive, via prices, to limit pollution, as opposed to a “command and control” fix that issues specific instructions in the form of regulations.

The initial reaction by many environmental activists to this idea was hostile, largely on moral grounds. Pollution, they felt, should be treated like a crime rather than something you have the right to do as long as you pay enough money. Moral concerns aside, there was also considerable skepticism about whether market incentives would actually be successful in reducing pollution. Even today, Pigovian taxes as originally envisaged are relatively rare. The most successful example I’ve been able to find is a Dutch tax on discharges of water containing organic materials.

What has caught on instead is a variant that most economists consider more or less equivalent: a system of tradable emissions permits, a k a cap and trade. In this model, a limited number of licenses to emit a specified pollutant, like sulfur dioxide, are issued. A business that wants to create more pollution than it is licensed for can go out and buy additional licenses from other parties; a firm that has more licenses than it intends to use can sell its surplus. This gives everyone an incentive to reduce pollution, because buyers would not have to acquire as many licenses if they can cut back on their emissions, and sellers can unload more licenses if they do the same. In fact, economically, a cap-and-trade system produces the same incentives to reduce pollution as a Pigovian tax, with the price of licenses effectively serving as a tax on pollution.

In practice there are a couple of important differences between cap and trade and a pollution tax. One is that the two systems produce different types of uncertainty. If the government imposes a pollution tax, polluters know what price they will have to pay, but the government does not know how much pollution they will generate. If the government imposes a cap, it knows the amount of pollution, but polluters do not know what the price of emissions will be. Another important difference has to do with government revenue. A pollution tax is, well, a tax, which imposes costs on the private sector while generating revenue for the government. Cap and trade is a bit more complicated. If the government simply auctions off licenses and collects the revenue, then it is just like a tax. Cap and trade, however, often involves handing out licenses to existing players, so the potential revenue goes to industry instead of the government.

Politically speaking, doling out licenses to industry isn’t entirely bad, because it offers a way to partly compensate some of the groups whose interests would suffer if a serious climate-change policy were adopted. This can make passing legislation more feasible.

These political considerations probably explain why the solution to the acid-rain predicament took the form of cap and trade and why licenses to pollute were distributed free to power companies. It’s also worth noting that the Waxman-Markey bill, a cap-and-trade setup for greenhouse gases that starts by giving out many licenses to industry but puts up a growing number for auction in later years, was actually passed by the House of Representatives last year; it’s hard to imagine a broad-based emissions tax doing the same for many years.

That’s not to say that emission taxes are a complete nonstarter. Some senators have recently floated a proposal for a sort of hybrid solution, with cap and trade for some parts of the economy and carbon taxes for others — mainly oil and gas. The political logic seems to be that the oil industry thinks consumers won’t blame it for higher gas prices if those prices reflect an explicit tax.

In any case, experience suggests that market-based emission controls work. Our recent history with acid rain shows as much. The Clean Air Act of 1990 introduced a cap-and-trade system in which power plants could buy and sell the right to emit sulfur dioxide, leaving it up to individual companies to manage their own business within the new limits. Sure enough, over time sulfur-dioxide emissions from power plants were cut almost in half, at a much lower cost than even optimists expected; electricity prices fell instead of rising. Acid rain did not disappear as a problem, but it was significantly mitigated. The results, it would seem, demonstrated that we can deal with environmental problems when we have to.

So there we have it, right? The emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases is a classic negative externality — the “biggest market failure the world has ever seen,” in the words of Nicholas Stern, the author of a report on the subject for the British government. Textbook economics and real-world experience tell us that we should have policies to discourage activities that generate negative externalities and that it is generally best to rely on a market-based approach.

Climate of Doubt?

This is an article on climate economics, not climate science. But before we get to the economics, it’s worth establishing three things about the state of the scientific debate.

The first is that the planet is indeed warming. Weather fluctuates, and as a consequence it’s easy enough to point to an unusually warm year in the recent past, note that it’s cooler now and claim, “See, the planet is getting cooler, not warmer!” But if you look at the evidence the right way — taking averages over periods long enough to smooth out the fluctuations — the upward trend is unmistakable: each successive decade since the 1970s has been warmer than the one before.

Second, climate models predicted this well in advance, even getting the magnitude of the temperature rise roughly right. While it’s relatively easy to cook up an analysis that matches known data, it is much harder to create a model that accurately forecasts the future. So the fact that climate modelers more than 20 years ago successfully predicted the subsequent global warming gives them enormous credibility.

Yet that’s not the conclusion you might draw from the many media reports that have focused on matters like hacked e-mail and climate scientists’ talking about a “trick” to “hide” an anomalous decline in one data series or expressing their wish to see papers by climate skeptics kept out of research reviews. The truth, however, is that the supposed scandals evaporate on closer examination, revealing only that climate researchers are human beings, too. Yes, scientists try to make their results stand out, but no data were suppressed. Yes, scientists dislike it when work that they think deliberately obfuscates the issues gets published. What else is new? Nothing suggests that there should not continue to be strong support for climate research.

And this brings me to my third point: models based on this research indicate that if we continue adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere as we have, we will eventually face drastic changes in the climate. Let’s be clear. We’re not talking about a few more hot days in the summer and a bit less snow in the winter; we’re talking about massively disruptive events, like the transformation of the Southwestern United States into a permanent dust bowl over the next few decades.

Now, despite the high credibility of climate modelers, there is still tremendous uncertainty in their long-term forecasts. But as we will see shortly, uncertainty makes the case for action stronger, not weaker. So climate change demands action. Is a cap-and-trade program along the lines of the model used to reduce sulfur dioxide the right way to go?

Serious opposition to cap and trade generally comes in two forms: an argument that more direct action — in particular, a ban on coal-fired power plants — would be more effective and an argument that an emissions tax would be better than emissions trading. (Let’s leave aside those who dismiss climate science altogether and oppose any limits on greenhouse-gas emissions, as well as those who oppose the use of any kind of market-based remedy.) There’s something to each of these positions, just not as much as their proponents think.

When it comes to direct action, you can make the case that economists love markets not wisely but too well, that they are too ready to assume that changing people’s financial incentives fixes every problem. In particular, you can’t put a price on something unless you can measure it accurately, and that can be both difficult and expensive. So sometimes it’s better simply to lay down some basic rules about what people can and cannot do.

Consider auto emissions, for example. Could we or should we charge each car owner a fee proportional to the emissions from his or her tailpipe? Surely not. You would have to install expensive monitoring equipment on every car, and you would also have to worry about fraud. It’s almost certainly better to do what we actually do, which is impose emissions standards on all cars.

Is there a comparable argument to be made for greenhouse-gas emissions? My initial reaction, which I suspect most economists would share, is that the very scale and complexity of the situation requires a market-based solution, whether cap and trade or an emissions tax. After all, greenhouse gases are a direct or indirect byproduct of almost everything produced in a modern economy, from the houses we live in to the cars we drive. Reducing emissions of those gases will require getting people to change their behavior in many different ways, some of them impossible to identify until we have a much better grasp of green technology. So can we really make meaningful progress by telling people specifically what will or will not be permitted? Econ 101 tells us — probably correctly — that the only way to get people to change their behavior appropriately is to put a price on emissions so this cost in turn gets incorporated into everything else in a way that reflects ultimate environmental impacts.

When shoppers go to the grocery store, for example, they will find that fruits and vegetables from farther away have higher prices than local produce, reflecting in part the cost of emission licenses or taxes paid to ship that produce. When businesses decide how much to spend on insulation, they will take into account the costs of heating and air-conditioning that include the price of emissions licenses or taxes for electricity generation. When electric utilities have to choose among energy sources, they will have to take into account the higher license fees or taxes associated with fossil-fuel consumption. And so on down the line. A market-based system would create decentralized incentives to do the right thing, and that’s the only way it can be done.

That said, some specific rules may be required. James Hansen, the renowned climate scientist who deserves much of the credit for making global warming an issue in the first place, has argued forcefully that most of the climate-change problem comes down to just one thing, burning coal, and that whatever else we do, we have to shut down coal burning over the next couple decades. My economist’s reaction is that a stiff license fee would strongly discourage coal use anyway. But a market-based system might turn out to have loopholes — and their consequences could be dire. So I would advocate supplementing market-based disincentives with direct controls on coal burning.

What about the case for an emissions tax rather than cap and trade? There’s no question that a straightforward tax would have many advantages over legislation like Waxman-Markey, which is full of exceptions and special situations. But that’s not really a useful comparison: of course an idealized emissions tax looks better than a cap-and-trade system that has already passed the House with all its attendant compromises. The question is whether the emissions tax that could actually be put in place is better than cap and trade. There is no reason to believe that it would be — indeed, there is no reason to believe that a broad-based emissions tax would make it through Congress.

To be fair, Hansen has made an interesting moral argument against cap and trade, one that’s much more sophisticated than the old view that it’s wrong to let polluters buy the right to pollute. What Hansen draws attention to is the fact that in a cap-and-trade world, acts of individual virtue do not contribute to social goals. If you choose to drive a hybrid car or buy a house with a small carbon footprint, all you are doing is freeing up emissions permits for someone else, which means that you have done nothing to reduce the threat of climate change. He has a point. But altruism cannot effectively deal with climate change. Any serious solution must rely mainly on creating a system that gives everyone a self-interested reason to produce fewer emissions. It’s a shame, but climate altruism must take a back seat to the task of getting such a system in place.

The bottom line, then, is that while climate change may be a vastly bigger problem than acid rain, the logic of how to respond to it is much the same. What we need are market incentives for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions — along with some direct controls over coal use — and cap and trade is a reasonable way to create those incentives.

But can we afford to do that? Equally important, can we afford not to?

The Cost of Action

Just as there is a rough consensus among climate modelers about the likely trajectory of temperatures if we do not act to cut the emissions of greenhouse gases, there is a rough consensus among economic modelers about the costs of action. That general opinion may be summed up as follows: Restricting emissions would slow economic growth — but not by much. The Congressional Budget Office, relying on a survey of models, has concluded that Waxman-Markey “would reduce the projected average annual rate of growth of gross domestic product between 2010 and 2050 by 0.03 to 0.09 percentage points.” That is, it would trim average annual growth to 2.31 percent, at worst, from 2.4 percent. Over all, the Budget Office concludes, strong climate-change policy would leave the American economy between 1.1 percent and 3.4 percent smaller in 2050 than it would be otherwise.

And what about the world economy? In general, modelers tend to find that climate-change policies would lower global output by a somewhat smaller percentage than the comparable figures for the United States. The main reason is that emerging economies like China currently use energy fairly inefficiently, partly as a result of national policies that have kept the prices of fossil fuels very low, and could thus achieve large energy savings at a modest cost. One recent review of the available estimates put the costs of a very strong climate policy — substantially more aggressive than contemplated in current legislative proposals — at between 1 and 3 percent of gross world product.

Such figures typically come from a model that combines all sorts of engineering and marketplace estimates. These will include, for instance, engineers’ best calculations of how much it costs to generate electricity in various ways, from coal, gas and nuclear and solar power at given resource prices. Then estimates will be made, based on historical experience, of how much consumers would cut back their electricity consumption if its price rises. The same process is followed for other kinds of energy, like motor fuel. And the model assumes that everyone makes the best choice given the economic environment — that power generators choose the least expensive means of producing electricity, while consumers conserve energy as long as the money saved by buying less electricity exceeds the cost of using less power in the form either of other spending or loss of convenience. After all this analysis, it’s possible to predict how producers and consumers of energy will react to policies that put a price on emissions and how much those reactions will end up costing the economy as a whole.

There are, of course, a number of ways this kind of modeling could be wrong. Many of the underlying estimates are necessarily somewhat speculative; nobody really knows, for instance, what solar power will cost once it finally becomes a large-scale proposition. There is also reason to doubt the assumption that people actually make the right choices: many studies have found that consumers fail to take measures to conserve energy, like improving insulation, even when they could save money by doing so.

But while it’s unlikely that these models get everything right, it’s a good bet that they overstate rather than understate the economic costs of climate-change action. That is what the experience from the cap-and-trade program for acid rain suggests: costs came in well below initial predictions. And in general, what the models do not and cannot take into account is creativity; surely, faced with an economy in which there are big monetary payoffs for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, the private sector will come up with ways to limit emissions that are not yet in any model.

What you hear from conservative opponents of a climate-change policy, however, is that any attempt to limit emissions would be economically devastating. The Heritage Foundation, for one, responded to Budget Office estimates on Waxman-Markey with a broadside titled, “C.B.O. Grossly Underestimates Costs of Cap and Trade.” The real effects, the foundation said, would be ruinous for families and job creation.

This reaction — this extreme pessimism about the economy’s ability to live with cap and trade — is very much at odds with typical conservative rhetoric. After all, modern conservatives express a deep, almost mystical confidence in the effectiveness of market incentives — Ronald Reagan liked to talk about the “magic of the marketplace.” They believe that the capitalist system can deal with all kinds of limitations, that technology, say, can easily overcome any constraints on growth posed by limited reserves of oil or other natural resources. And yet now they submit that this same private sector is utterly incapable of coping with a limit on overall emissions, even though such a cap would, from the private sector’s point of view, operate very much like a limited supply of a resource, like land. Why don’t they believe that the dynamism of capitalism will spur it to find ways to make do in a world of reduced carbon emissions? Why do they think the marketplace loses its magic as soon as market incentives are invoked in favor of conservation?

Clearly, conservatives abandon all faith in the ability of markets to cope with climate-change policy because they don’t want government intervention. Their stated pessimism about the cost of climate policy is essentially a political ploy rather than a reasoned economic judgment. The giveaway is the strong tendency of conservative opponents of cap and trade to argue in bad faith. That Heritage Foundation broadside accuses the Congressional Budget Office of making elementary logical errors, but if you actually read the office’s report, it’s clear that the foundation is willfully misreading it. Conservative politicians have been even more shameless. The National Republican Congressional Committee, for example, issued multiple press releases specifically citing a study from M.I.T. as the basis for a claim that cap and trade would cost $3,100 per household, despite repeated attempts by the study’s authors to get out the word that the actual number was only about a quarter as much.

The truth is that there is no credible research suggesting that taking strong action on climate change is beyond the economy’s capacity. Even if you do not fully trust the models — and you shouldn’t — history and logic both suggest that the models are overestimating, not underestimating, the costs of climate action. We can afford to do something about climate change.

But that’s not the same as saying we should. Action will have costs, and these must be compared with the costs of not acting. Before I get to that, however, let me touch on an issue that will become central if we actually do get moving on climate policy: how to get the rest of the world to go along with us.

The China Syndrome

The United States is still the world’s largest economy, which makes the country one of the world’s largest sources of greenhouse gases. But it’s not the largest. China, which burns much more coal per dollar of gross domestic product than the United States does, overtook us by that measure around three years ago. Over all, the advanced countries — the rich man’s club comprising Europe, North America and Japan — account for only about half of greenhouse emissions, and that’s a fraction that will fall over time. In short, there can’t be a solution to climate change unless the rest of the world, emerging economies in particular, participates in a major way.

Inevitably those who resist tackling climate change point to the global nature of emissions as a reason not to act. Emissions limits in America won’t accomplish much, they argue, if China and others don’t match our effort. And they highlight China’s obduracy in the Copenhagen negotiations as evidence that other countries will not cooperate. Indeed, emerging economies feel that they have a right to emit freely without worrying about the consequences — that’s what today’s rich countries got to do for two centuries. It’s just not possible to get global cooperation on climate change, goes the argument, and that means there is no point in taking any action at all.

For those who think that taking action is essential, the right question is how to persuade China and other emerging nations to participate in emissions limits. Carrots, or positive inducements, are one answer. Imagine setting up cap-and-trade systems in China and the United States — but allow international trading in permits, so Chinese and American companies can trade emission rights. By setting overall caps at levels designed to ensure that China sells us a substantial number of permits, we would in effect be paying China to cut its emissions. Since the evidence suggests that the cost of cutting emissions would be lower in China than in the United States, this could be a good deal for everyone.

But what if the Chinese (or the Indians or the Brazilians, etc.) do not want to participate in such a system? Then you need sticks as well as carrots. In particular, you need carbon tariffs.

A carbon tariff would be a tax levied on imported goods proportional to the carbon emitted in the manufacture of those goods. Suppose that China refuses to reduce emissions, while the United States adopts policies that set a price of $100 per ton of carbon emissions. If the United States were to impose such a carbon tariff, any shipment to America of Chinese goods whose production involved emitting a ton of carbon would result in a $100 tax over and above any other duties. Such tariffs, if levied by major players — probably the United States and the European Union — would give noncooperating countries a strong incentive to reconsider their positions.

To the objection that such a policy would be protectionist, a violation of the principles of free trade, one reply is, So? Keeping world markets open is important, but avoiding planetary catastrophe is a lot more important. In any case, however, you can argue that carbon tariffs are well within the rules of normal trade relations. As long as the tariff imposed on the carbon content of imports is comparable to the cost of domestic carbon licenses, the effect is to charge your own consumers a price that reflects the carbon emitted in what they buy, no matter where it is produced. That should be legal under international-trading rules. In fact, even the World Trade Organization, which is charged with policing trade policies, has published a study suggesting that carbon tariffs would pass muster.

Needless to say, the actual business of getting cooperative, worldwide action on climate change would be much more complicated and tendentious than this discussion suggests. Yet the problem is not as intractable as you often hear. If the United States and Europe decide to move on climate policy, they almost certainly would be able to cajole and chivvy the rest of the world into joining the effort. We can do this.

The Costs of Inaction

In public discussion, the climate-change skeptics have clearly been gaining ground over the past couple of years, even though the odds have been looking good lately that 2010 could be the warmest year on record. But climate modelers themselves have grown increasingly pessimistic. What were previously worst-case scenarios have become base-line projections, with a number of organizations doubling their predictions for temperature rise over the course of the 21st century. Underlying this new pessimism is increased concern about feedback effects — for example, the release of methane, a significant greenhouse gas, from seabeds and tundra as the planet warms.

At this point, the projections of climate change, assuming we continue business as usual, cluster around an estimate that average temperatures will be about 9 degrees Fahrenheit higher in 2100 than they were in 2000. That’s a lot — equivalent to the difference in average temperatures between New York and central Mississippi. Such a huge change would have to be highly disruptive. And the troubles would not stop there: temperatures would continue to rise.

Furthermore, changes in average temperature will by no means be the whole story. Precipitation patterns will change, with some regions getting much wetter and others much drier. Many modelers also predict more intense storms. Sea levels would rise, with the impact intensified by those storms: coastal flooding, already a major source of natural disasters, would become much more frequent and severe. And there might be drastic changes in the climate of some regions as ocean currents shift. It’s always worth bearing in mind that London is at the same latitude as Labrador; without the Gulf Stream, Western Europe would be barely habitable.

While there may be some benefits from a warmer climate, it seems almost certain that upheaval on this scale would make the United States, and the world as a whole, poorer than it would be otherwise. How much poorer? If ours were a preindustrial, primarily agricultural society, extreme climate change would be obviously catastrophic. But we have an advanced economy, the kind that has historically shown great ability to adapt to changed circumstances. If this sounds similar to my argument that the costs of emissions limits would be tolerable, it ought to: the same flexibility that should enable us to deal with a much higher carbon prices should also help us cope with a somewhat higher average temperature.

But there are at least two reasons to take sanguine assessments of the consequences of climate change with a grain of salt. One is that, as I have just pointed out, it’s not just a matter of having warmer weather — many of the costs of climate change are likely to result from droughts, flooding and severe storms. The other is that while modern economies may be highly adaptable, the same may not be true of ecosystems. The last time the earth experienced warming at anything like the pace we now expect was during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, about 55 million years ago, when temperatures rose by about 11 degrees Fahrenheit over the course of around 20,000 years (which is a much slower rate than the current pace of warming). That increase was associated with mass extinctions, which, to put it mildly, probably would not be good for living standards.

So how can we put a price tag on the effects of global warming? The most widely quoted estimates, like those in the Dynamic Integrated Model of Climate and the Economy, known as DICE, used by Yale’s William Nordhaus and colleagues, depend upon educated guesswork to place a value on the negative effects of global warming in a number of crucial areas, especially agriculture and coastal protection, then try to make some allowance for other possible repercussions. Nordhaus has argued that a global temperature rise of 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit — which used to be the consensus projection for 2100 — would reduce gross world product by a bit less than 2 percent. But what would happen if, as a growing number of models suggest, the actual temperature rise is twice as great? Nobody really knows how to make that extrapolation. For what it’s worth, Nordhaus’s model puts losses from a rise of 9 degrees at about 5 percent of gross world product. Many critics have argued, however, that the cost might be much higher.

Despite the uncertainty, it’s tempting to make a direct comparison between the estimated losses and the estimates of what the mitigation policies will cost: climate change will lower gross world product by 5 percent, stopping it will cost 2 percent, so let’s go ahead. Unfortunately the reckoning is not that simple for at least four reasons.

First, substantial global warming is already “baked in,” as a result of past emissions and because even with a strong climate-change policy the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is most likely to continue rising for many years. So even if the nations of the world do manage to take on climate change, we will still have to pay for earlier inaction. As a result, Nordhaus’s loss estimates may overstate the gains from action.

Second, the economic costs from emissions limits would start as soon as the policy went into effect and under most proposals would become substantial within around 20 years. If we don’t act, meanwhile, the big costs would probably come late this century (although some things, like the transformation of the American Southwest into a dust bowl, might come much sooner). So how you compare those costs depends on how much you value costs in the distant future relative to costs that materialize much sooner.

Third, and cutting in the opposite direction, if we don’t take action, global warming won’t stop in 2100: temperatures, and losses, will continue to rise. So if you place a significant weight on the really, really distant future, the case for action is stronger than even the 2100 estimates suggest.

Finally and most important is the matter of uncertainty. We’re uncertain about the magnitude of climate change, which is inevitable, because we’re talking about reaching levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere not seen in millions of years. The recent doubling of many modelers’ predictions for 2100 is itself an illustration of the scope of that uncertainty; who knows what revisions may occur in the years ahead. Beyond that, nobody really knows how much damage would result from temperature rises of the kind now considered likely.

You might think that this uncertainty weakens the case for action, but it actually strengthens it. As Harvard’s Martin Weitzman has argued in several influential papers, if there is a significant chance of utter catastrophe, that chance — rather than what is most likely to happen — should dominate cost-benefit calculations. And utter catastrophe does look like a realistic possibility, even if it is not the most likely outcome.

Weitzman argues — and I agree — that this risk of catastrophe, rather than the details of cost-benefit calculations, makes the most powerful case for strong climate policy. Current projections of global warming in the absence of action are just too close to the kinds of numbers associated with doomsday scenarios. It would be irresponsible — it’s tempting to say criminally irresponsible — not to step back from what could all too easily turn out to be the edge of a cliff.

Still that leaves a big debate about the pace of action.

The Ramp Versus the Big Bang

Economists who analyze climate policies agree on some key issues. There is a broad consensus that we need to put a price on carbon emissions, that this price must eventually be very high but that the negative economic effects from this policy will be of manageable size. In other words, we can and should act to limit climate change. But there is a ferocious debate among knowledgeable analysts about timing, about how fast carbon prices should rise to significant levels.

On one side are economists who have been working for many years on so-called integrated-assessment models, which combine models of climate change with models of both the damage from global warming and the costs of cutting emissions. For the most part, the message from these economists is a sort of climate version of St. Augustine’s famous prayer, “Give me chastity and continence, but not just now.” Thus Nordhaus’s DICE model says that the price of carbon emissions should eventually rise to more than $200 a ton, effectively more than quadrupling the cost of coal, but that most of that increase should come late this century, with a much more modest initial fee of around $30 a ton. Nordhaus calls this recommendation for a policy that builds gradually over a long period the “climate-policy ramp.”

On the other side are some more recent entrants to the field, who work with similar models but come to different conclusions. Most famously, Nicholas Stern, an economist at the London School of Economics, argued in 2006 for quick, aggressive action to limit emissions, which would most likely imply much higher carbon prices. This alternative position doesn’t appear to have a standard name, so let me call it the “climate-policy big bang.”

I find it easiest to make sense of the arguments by thinking of policies to reduce carbon emissions as a sort of public investment project: you pay a price now and derive benefits in the form of a less-damaged planet later. And by later, I mean much later; today’s emissions will affect the amount of carbon in the atmosphere decades, and possibly centuries, into the future. So if you want to assess whether a given investment in emissions reduction is worth making, you have to estimate the damage that an additional ton of carbon in the atmosphere will do, not just this year but for a century or more to come; and you also have to decide how much weight to place on harm that will take a very long time to materialize.

The policy-ramp advocates argue that the damage done by an additional ton of carbon in the atmosphere is fairly low at current concentrations; the cost will not get really large until there is a lot more carbon dioxide in the air, and that won’t happen until late this century. And they argue that costs that far in the future should not have a large influence on policy today. They point to market rates of return, which indicate that investors place only a small weight on the gains or losses they expect in the distant future, and argue that public policies, including climate policies, should do the same.

The big-bang advocates argue that government should take a much longer view than private investors. Stern, in particular, argues that policy makers should give the same weight to future generations’ welfare as we give to those now living. Moreover, the proponents of fast action hold that the damage from emissions may be much larger than the policy-ramp analyses suggest, either because global temperatures are more sensitive to greenhouse-gas emissions than previously thought or because the economic damage from a large rise in temperatures is much greater than the guesstimates in the climate-ramp models.

As a professional economist, I find this debate painful. There are smart, well-intentioned people on both sides — some of them, as it happens, old friends and mentors of mine — and each side has scored some major points. Unfortunately, we can’t just declare it an honorable draw, because there’s a decision to be made.

Personally, I lean toward the big-bang view. Stern’s moral argument for loving unborn generations as we love ourselves may be too strong, but there’s a compelling case to be made that public policy should take a much longer view than private markets. Even more important, the policy-ramp prescriptions seem far too much like conducting a very risky experiment with the whole planet. Nordhaus’s preferred policy, for example, would stabilize the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at a level about twice its preindustrial average. In his model, this would have only modest effects on global welfare; but how confident can we be of that? How sure are we that this kind of change in the environment would not lead to catastrophe? Not sure enough, I’d say, particularly because, as noted above, climate modelers have sharply raised their estimates of future warming in just the last couple of years.

So what I end up with is basically Martin Weitzman’s argument: it’s the nonnegligible probability of utter disaster that should dominate our policy analysis. And that argues for aggressive moves to curb emissions, soon.

The Political Atmosphere

As I’ve mentioned, the House has already passed Waxman-Markey, a fairly strong bill aimed at reducing greenhouse-gas emissions. It’s not as strong as what the big-bang advocates propose, but it appears to move faster than the policy-ramp proposals. But the vote on Waxman-Markey, which was taken last June, revealed a starkly divided Congress. Only 8 Republicans voted in favor of it, while 44 Democrats voted against. And the odds are that it would not pass if it were brought up for a vote today.

Prospects in the Senate, where it takes 60 votes to get most legislation through, are even worse. A number of Democratic senators, representing energy-producing and agricultural states, have come out against cap and trade (modern American agriculture is strongly energy-intensive). In the past, some Republican senators have supported cap and trade. But with partisanship on the rise, most of them have been changing their tune. The most striking about-face has come from John McCain, who played a leading role in promoting cap and trade, introducing a bill broadly similar to Waxman-Markey in 2003. Today McCain lambastes the whole idea as “cap and tax,” to the dismay of former aides.

Oh, and a snowy winter on the East Coast of the U.S. has given climate skeptics a field day, even though globally this has been one of the warmest winters on record.

So the immediate prospects for climate action do not look promising, despite an ongoing effort by three senators — John Kerry, Joseph Lieberman and Lindsey Graham — to come up with a compromise proposal. (They plan to introduce legislation later this month.) Yet the issue isn’t going away. There’s a pretty good chance that the record temperatures the world outside Washington has seen so far this year will continue, depriving climate skeptics of one of their main talking points. And in a more general sense, given the twists and turns of American politics in recent years — since 2005 the conventional wisdom has gone from permanent Republican domination to permanent Democratic domination to God knows what — there has to be a real chance that political support for action on climate change will revive.

If it does, the economic analysis will be ready. We know how to limit greenhouse-gas emissions. We have a good sense of the costs — and they’re manageable. All we need now is the political will.

***************************************************************************

Growth and Greenhouse Gases, Paul Krugman, April 13 2010.

So I’ve gotten some pushback from environmentalists on the proposition in my mag piece that we can afford, at real but modest cost, to limit greenhouse gas emissions. Oddly, it comes from two directions. On one side, there are those who insist that greening the economy is win-win: more jobs, more growth, as well as less carbon. On the other, those who insist that you can only be serious about protecting the planet if you admit that we have to give up on economic growth.

On the first: there is actually a fair bit of evidence that many energy-saving measures would also be cost-saving, even at current prices. Like most economists, I take these estimates with a grain of salt: if these actions really are cost-saving, why aren’t they being taken already? Isn’t that an indication that there are hidden costs? That said, in the real world people aren’t perfectly rational, so there may well be energy-saving measures with negative cost that aren’t being undertaken. What I would argue, however, is that given the size of the adjustment we need to make, these free-lunch savings won’t take us anywhere close to all the way.

On the pessimists: there’s a tendency for some environmentalists to adopt a sort of mechanistic view of the economy, in which there’s a one-to-one correspondence between real GDP and carbon emissions (oddly, people on the right tend to assert the same equivalence, using it to argue that we can’t afford to deal with climate change).

In fact, there’s much more choice and flexibility involved.

One way to think about this is to look at where the greenhouse gas emissions come from, as in the chart above. Looking at that chart, I think you can glimpse the nature of the adjustment we have to make.

First, power generation has to be “decarbonized”: solar, nuclear, wind, geothermal, and maybe some fossil fuels with carbon capture have to replace coal-fired plants. This is within the reach of current technologies.

Second, residential and commercial use — much of it for heating — also has to be largely decarbonized; if power generation is decarbonized, much of this can be done by switching to electricity.

The hard part is transportation. What will happen there is probably a mix of approaches; greater efficiency; electrification (including things like plug-in hybrids); lower-emissions fuels (natural gas for sure; hydrogen?); and other things we haven’t thought of.

All of this is consistent with a growing economy. I won’t say that it’s easy; but given the right incentives, we can do this.

***************************************************************************

Lies, Damned Lies, and Growth, Paul Krugman, May 24 2010.

Scott Sumner says that I’m wrong about taxes, regulation, and growth, because although American growth has slowed since deregulation and all that, the growth has been better than we might have expected.

We can try to parse whether that’s true — but in any case it’s not a response to my original point. That was about the claim, quite common on the right, that the US economy was stagnant until Reagan did away with those nasty New Deal policies — a claim that is simply, flatly, false. The era of strong unions, high minimum wages, high top marginal tax rates, etc. was also a period of rapid growth and rising living standards. That doesn’t prove causation; it does disprove the widespread dogma that these things are always economically devastating. And it’s telling that so many on the right have airbrushed the whole postwar generation out of history.

Given all that, what do we learn from the fact that since 1980 the United States has more or less maintained its relative GDP per capita, after substantial decline previously? Well, that’s not a simple story. Part of the answer is that our relative decline for 30 years after WWII largely reflected technological catchup by others; by the 80s that catchup was largely over, with all advanced nations at roughly the same technological level, so there was no reason to expect faster growth in Europe and Japan.

There’s also an issue of labor-leisure choices. In the 70s the long-run trend of taking productivity gains out partly in the form of shorter working hours came to an end in the US, while continuing elsewhere. What that’s about is the subject of dispute, but it’s important to understand that a large part of the GDP difference between the US and Europe reflects that choice. France, in particular, is a country with about the same level of technology and productivity as America, but with roughly 25 percent lower GDP per capita; this mainly reflects longer vacations and earlier retirement, which may or may not be bad things, but are not a straightforward case of inferior performance.

But back to the original point: where this all started was with the common assertion that the US economy was a failure until Reagan came along. This should be true, according to doctrine — so that’s what people believe happened, even though it didn’t.

***************************************************************************

Limits to growth and related stuff, Paul Krugman, April 22 2008.

I’ve been getting some correspondence asking me where today’s resource concerns fit with the old “Limits to growth” stuff that received a lot of publicity 30+ years ago. Actually, there’s a bit of a backstory there.

In 1973-4, my junior and senior years in college, I was Bill Nordhaus’s research assistant, working on energy issues. (This is the same Bill Nordhaus who warned back in 2002 that the cost of the Iraq war would probably be a lot higher than the Bushies were letting on.) I spent much of the summer of 1973, in particular, in Yale’s wonderful geology library — though the real import of what I learned there didn’t sink in for a while, as I’ll explain in a bit.

Nordhaus, among other things, wrote a hostile review of Jay Forrester’s World Dynamics, which led to the later Limits to Growth. The essential story there was one of hard-science arrogance: Forrester, an eminent professor of engineering, decided to try his hand at economics, and basically said, “I’m going to do economics with equations! And run them on a computer! I’m sure those stupid economists have never thought of that!” And he didn’t walk over to the east side of campus to ask whether, in fact, any economists ever had thought of that, and what they had learned. (Economists tend to do the same thing to sociologists and political scientists. The general rule to remember is that if some discipline seems less developed than your own, it’s probably not because the researchers aren’t as smart as you are, it’s because the subject is harder.)

As a result, the study was a classic case of garbage-in-garbage-out: Forrester didn’t know anything about the empirical evidence on economic growth or the history of past modeling efforts, and it showed. The insistence of his acolytes that the work must be scientific, because it came out of a computer, only made things worse.

All this is old history. But there’s something else I learned from that summer, which is important.

Much of what I did back then was look for estimates of the cost of alternative energy sources, which played a big role in Nordhaus’s big paper that year. (Readers with access to JSTOR might want to look at the acknowledgments on the first page.) And the estimates — mainly from Bureau of Mines publications — were optimistic. Shale oil, coal gasification, and eventually the breeder reactor would satisfy our energy needs at not-too-high prices when the conventional oil ran out.

None of it happened. OK, Athabasca tar sands have finally become a significant oil source, but even there it’s much more expensive — and environmentally destructive — than anyone seemed to envision in the early 70s.

You might say that this is my answer to those who cheerfully assert that human ingenuity and technological progress will solve all our problems. For the last 35 years, progress on energy technologies has consistently fallen below expectations.

I’d actually suggest that this is true not just for energy but for our ability to manipulate the physical world in general: 2001 didn’t look much like 2001, and in general material life has been relatively static. (How do the changes in the way we live between 1958 and 2008 compare with the changes between 1908 and 1958? I think the answer is obvious.)

But anyway, while the Limits to Growth stuff of the 1970s was a mess, the history of energy technology doesn’t support extreme optimism, either.

***************************************************************************

September 1, 1939, W.H. Auden.

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.

Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago made

A psychopathic god:

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About Democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analysed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief:

We must suffer them all again.

Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man,

Each language pours its vain

Competitive excuse:

But who can live for long

In an euphoric dream;

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism's face

And the international wrong.

Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day:

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shout

Is not so crude as our wish:

What mad Nijinsky wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark

Into the ethical life

The dense commuters come,

Repeating their morning vow;

'I will be true to the wife,

I'll concentrate more on my work,'

And helpless governors wake

To resume their compulsory game:

Who can release them now,

Who can reach the dead,

Who can speak for the dumb?

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

Defenseless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

***************************************************************************

Dover Beach, Matthew Arnold, 1867.

The sea is calm to-night.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand;

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the A gaean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth's shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.