Up, Down, Appendices, Postscript.

There was an old woman who swallowed a fly.

I don't know why she swallowed the fly.

Perhaps she'll die.

There was an old woman who swallowed a spider.

It wiggled and wiggled and tickled inside her.

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly.

I don't know why she swallowed the fly.

Perhaps she'll die.

There was an old woman who swallowed a bird;

How absurd, to swallow a bird.

She swallowed the bird to catch the spider

That wiggled and wiggled and tickled inside her.

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly.

I don't know why she swallowed the fly.

Perhaps she'll die.

There was an old woman who swallowed a cat.

Imagine that, she swallowed a cat.

She swallowed the cat to catch the bird ...

She swallowed the bird to catch the spider

That wiggled and wiggled and tickled inside her.

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly.

I don't know why she swallowed the fly.

Perhaps she'll die.

There was an old woman who swallowed a dog.

What a hog! She swallowed a dog!

She swallowed the dog to catch the cat ...

She swallowed the cat to catch the bird ...

She swallowed the bird to catch the spider

That wiggled and wiggled and tickled inside her.

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly.

But I don't know why she swallowed the fly.

Perhaps she'll die.

There was an old woman who swallowed a goat.

Just opened her throat and swallowed a goat!

She swallowed the goat to catch the dog ...

She swallowed the dog to catch the cat ...

She swallowed the cat to catch the bird ...

She swallowed the bird to catch the spider

That wiggled and wiggled and tickled inside her.

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly.

But I don't know why she swallowed the fly.

Perhaps she'll die.

There was an old woman who swallowed a cow.

I don't know how she swallowed a cow.

She swallowed the cow to catch the goat ...

She swallowed the goat to catch the dog ...

She swallowed the dog to catch the cat ...

She swallowed the cat to catch the bird ...

She swallowed the bird to catch the spider

That wiggled and wiggled and tickled inside her.

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly.

But I don't know why she swallowed the fly.

Perhaps she'll die.

There was an old woman who swallowed a horse.

She's dead, of course.

I have told the story of the spruce bud worm and the shrews and the snakes elsewhere in the blog ... it is probably apocryphal, an 'urban myth' or rural as the case may be - I had it from Harold Ryan of Great Paradise, Placentia Bay sometime around 1969 who told me about the shrews 'moving like a blanket' over the ground.

Or wood-coal-oil-gas-nuclear ... whatever.

From Vias de Fato comes this news:

| | ARROMBAMENTO NA COMISSÃO PASTORAL DA TERRA DE PINHEIRO, Sexta-feira, 15 de Julho de 2011.

A Comissão Pastoral da Terra (CPT), de Pinheiro foi arrombada na madrugada desta sexta-feira (15). Essa é mais uma violência praticada contra escritórios da CPT no Maranhão. No último final de semana a CPT esteve reunida junto com o Movimento Quilombola da Baixada Maranhense –MOQUIBOM, com mais de 55 comunidades quilombolas, no município de Mangabeira. “É muito suspeito tudo isso, toda vez que realizamos um importante encontro com os quilombolas, alguma sede da CPT aparece arrombada. Dessa vez, fizeram diferente, além de revirarem algumas coisas, levaram o computador, quando arrombaram a de São Luís, reviraram tudo mais não levaram nenhum objeto de valor.” Disse por telefone, Fábio Costa, agente da CPT de Pinheiro.

O arrombamento só foi percebido pela manhã por um porteiro do colégio Pinheirense, localizado em frente ao escritório da entidade na Avenida Presidente Dutra, em Pinheiro. Por volta das 7h da manhã, o porteiro percebeu que as portas estavam abertas e não tinha nenhum agente da CPT no local. O porteiro então, entrou em contato com a diretora da escola que ligou para Fábio que se encontrava no município de Bequimão, retornando de imediato. Não foi possível contactar o Padre Inaldo Serejo, coordenador da CPT, pois o mesmo encontra-se em um encontro de Dioceses que está sendo realizado em Caxias. | | CPT OFFICE IN PINHEIRO TRASHED, Friday July 15 2011.

The Pastoral Land Commission's office in Pinheiro was trashed in the early morning of Friday the 15th. This is yet another violent action against the offices of the CPT in Maranhão (state). Last weekend the CPT joined with the Maranhão Lowlands Ex-slaves Movement (MOQUIBOM), comprising more than 55 communities in Mangabeira municipality. “This is all very suspicious, every time we achieve an important meeting with the ex-slaves, one of our offices gets trashed. This time they did it differently - as well as turning things upside down they took the computer. When they broke up the office in São Luis they did not take anything of value." This by telephone with Fábio Costa, CPT agent in Pinheiro.

The destruction was discovered about 7AM by the doorman of the Pinheiro College, across the street from the CPT office on Avenida Presidente Dutra, in Pinheiro. About 7AM the doorman noticed that the doors were open with no one from the CPT present. So he got in contact with the director of the school who managed to find Fábio in Bequimão municipality. It was not possible to contact Father Inaldo Serejo, the CPT coordinator, because he was at a meeting of the Diocese in Caxias. |

Here's a map with the places in the story marked. Interesting that you can zoom right into the streets of Pinheiro. Avenida Presidente Dutra doesn't seem to be there which is maybe par for Google, but some of the streets are probably approximately so ... there is an Avenida Eurico Dutra showing, maybe that's it.

The good news (good?) is that they now have three suspects in the murders of Ze Claudio & Maria: José Rodrigues Moreira (the landowner who ordered it), Lindon Jonson Silva Rocha (his brother) and Alberto Lopes Teixeira (an accomplice). Now they have to catch 'em. (source)

The ugly question remains: Did one landowner act alone? How many others were complicit?

Khalil Bendib, cartoonist from Berkeley, available here & here.

Khalil Bendib, cartoonist from Berkeley, available here & here.

What I am musing on these days is often this: "What will it take for the muggles to figgure it out?" Not much of a nevermind that it'll be too late by then.

Seri: I take one step. I take another. I take a fifth step ... How did I ever live without Twitter?

Seri: I take one step. I take another. I take a fifth step ... How did I ever live without Twitter?

You can find Seri here. Rudy Park uses a big conglomerate site with irritating popups so I will not publish the link - easy enough to find if you want to see more.

Maybe that last step will look something like this:

There are so many tipping points, collective, several & individual ...

There are so many tipping points, collective, several & individual ...

Here's a story: There was a heat wave in Toronto last week - 38°! The horror! Highest temperature reading ever! Or maybe close. Warnings in the newspaper for those over 65. But this apartment has windows on two sides, south & east, and there has always seemed to be a breeze to keep things comfortable ... until the day before yesterday when it ... stopped.

Who knows why? Some tiny effect somewhere among all of the baffles between here and the lake has tipped. So now there is a small fan dragging air in under my garden. The Home Depot was just about out of fans. Selling like hotcakes. A situation redeeemed only by the lovely young woman taking the money.

Who knows why? Some tiny effect somewhere among all of the baffles between here and the lake has tipped. So now there is a small fan dragging air in under my garden. The Home Depot was just about out of fans. Selling like hotcakes. A situation redeeemed only by the lovely young woman taking the money.

I see Tom Toles via the NYT & Ygreck here.

We can only hope that whichever bureaucratic maggot will be the one to put the last straw on the camel's back gets around to it soon.

I read this thing once, a year or so ago. I found it artificial, stereotyped, cloying, impossible in its details ... and sent it back to the library. Forgot about it. Then some recent noise made me remember it - but I couldn't quite remember why I had disliked it so, so I read it again.

Chanda's Secrets by Allan Stratton: at the library, his blog, the blurb at Annick Press with a long list of honours & hyperbolic mini-reviews by the likes of Stephen Lewis ... a cute little Aids ribbon instead of an apostrophe in the title ... and all ...

I wanted to scan the entire thing, shred it sentence by phoney sentence ... no steam for that as it turns out, but here is Chapter 1.

Hell, colleagues of mine, good friends some of them, have died of Aids - so why does the entire phenomenon of this book and its author's success and the subsequent movie fill me with such revulsion?

I'm gonna just leave it to you ... eventually I will see the movie Life, Above All ... here's the trailer.

Clever of him to pose & pitch it as an 'adolescent' novel - saves wear and tear on the thinking machine. Or m-maybe the m-mercury & low-level radioactivity is kicking in faster than anticipated and double-digit IQs are already the standard for tops.

Or explain to me how there can be such dreck as Republic of Doyle? I was there a few years ago - this looks like a sitcom but it is nothing but the truth. The place is gone. Sold.

The environmental whiners are calling out the petition troops over proposed cuts to Toronto's environmental programs - nevermind that the so called programs are entirely ineffective except as a trough for the entitled.

And Margaret Atwood is doing the same around threatened cuts to the Toronto Public Library. Well, the library does matter - but our clever Wile-e-coyote Rob Ford is just sending them up, a distraction - he's not going to close the libraries.

Here's Robert Preston and Shirley Jones in 1962.

A few 'factoids' from CUPE/TPLWU:2,400 members

Pages: There are 699 Pages who perform various front line library tasks. All are part-time workers. Current hourly rate varies from $11.33 to $14.95.

Public Service Assistants: There are 533 PSAs who assist patrons in many ways. 50 per cent work part-time. The current top PSA wage rate is $26.63.

Librarians: There are 242 Librarians. The current top Librarian wage rate is $39.01, which is comparable to a college instructor.

which comes to about 1,400 - so how much do the other 1,000 make?

And a few from the 2011 Library Budget (read it yourself).

Here's the lady on the front line, Jane Pyper. And here she is speaking.

Here's the lady on the front line, Jane Pyper. And here she is speaking.

Here's her recent proposal to save 500,000 a year.

Keep in mind that the Toronto Public Library is about the only thing in this entire city that actually works.

Whatever.

Crisis this and crisis that ... Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Eurozone, Debt Ceiling, TPL closures ... all bogus. The powers that be and their PHD bureaucrat sleveens can't let it go because they would lose their salaries & perks, so they cobble up ineffective compromises & half measures, all the while taking whatever advantage accrues from the Shock & Awe of it for themselves. And all the while ignoring the elephant in the room - which is the broken environment.

Of course it is not only the environment that is broken. I have been re-reading The Limits to Growth, the library only holds a few copies in the reference section, not for circulation, but I have my own copy. The last sentence is:The crux of the matter is not only whether the human species will survive, but even more whether it can survive without falling into a state of worthless existence.

So ... worthless existence ... One wonders, or, I do at least, if they were agnostics or athiests or believers?

I sometimes turn to Northrop Frye's Double Vision. Other times I turn to Hannah Arendt's Men in Dark Times. The title comes from a poem by Bertolt Brecht, An die Nachgeborenen, not so unlike Auden's September 1, 1939, written about the same time.

I like the way she talks about official lies. It's an old tradition, going back at least to the 'mouth, lips, and fat' imagery in the Psalms: here in #17, "They are inclosed in their own fat: with their mouth they speak proudly," and particularly in #73, "Their eyes stand out with fatness: they have more than heart could wish," which Martin Buber wrote so eloquently about.

See how the dimwit dilettante is driven to shameless name dropping? And even beyond that. (Wait for it, here it comes.) Because I look at these words (of Brecht & Auden), which were, after all, coming out of mere world wars and holocaust genocides ...

See how the dimwit dilettante is driven to shameless name dropping? And even beyond that. (Wait for it, here it comes.) Because I look at these words (of Brecht & Auden), which were, after all, coming out of mere world wars and holocaust genocides ...

OK, picture Dadaab in your mind, or Dollo Ado, or Ali Addeh, and what is going on there, and in a dozen and a hundred and a thousand other such camps. Here's a map. A-and worse - what is going on just outside these camps.

Joe Hall & the Continental Drift with Here Comes Da 3rd World ... and maybe a chorous of Eva B.

Aporrinhando as almofadinhas.

Be well.

Postscript:

From the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation comes an open-ended Request for Proposals (RFP), the Reinvent the Toilet Challenge: Invent a toilet, with no sewage, water or electrical connection, which renders waste in approximately 24 hours for 5 cents a day per user.

Watch the video (above right, 1½ minutes) & read the RFP (9 pages).

UofT has snagged one of the contracts (read about it in the Star or Globe) headed by professor Yu-Ling Cheng. You can watch and listen to her in this 4 minute video.

UofT has snagged one of the contracts (read about it in the Star or Globe) headed by professor Yu-Ling Cheng. You can watch and listen to her in this 4 minute video.

She doesn't smile much - but she does smile.

There are strong reasons to stop flushing. The phosphorus cycle & peak phosphorus; thermodynamics; whatever ... I can't remember it all now ... They have been obvious since the 60's, just like the rest of the broken environment.

The public utility bureaucrats will soon figgure out that this notion seriously undermines their positions and condemn it accordingly - because if it works in 'developing countries' it will work here too. I hereby christen the inevitable controversy, 'ShitGate'.

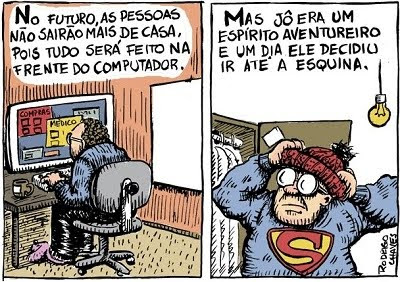

Check this out: Rodrigo Chaves:

| | In the future, people will no longer leave the house, because everything will be done at a computer screen.

But Joe was an adventurous spirit, and one day he decided to go to the corner.

Arriving there he saw something he had never seen before in his life.

"Got any spare change buddy?"

Then Joe ran back to the house to tell about what had happened:

"I saw a living woman! And she talked to me! Does this mean we had sex? I think I'm in love ..."" |

Appendices:

1. Chanda's Secrets Part One, 1, Allan Stratton, 2004.

2. An die Nachgeborenen / To Those Who Follow in Our Wake, Bertolt Brecht, 1939(?).

3. Men in Dark Times Preface, Hannah Arendt, 1968.

4. The Heart Determines: Psalm 73 Martin Buber, 1968.

Chanda's Secrets Part One, 1, Allan Stratton, 2004.

PART ONEI'M ALONE IN THE OFFICE of Bateman's Eternal Light Funeral Services. It's early Monday morning and Mr. Bateman is busy with a new shipment of coffins.

"I'll get to you as soon as I can," he told me. "Meanwhile, you can go into my office and look at my fish. They're in an aquarium on the far wall. If you get bored, there're magazines on the coffee table. By the way, I'm sorry about your sister."

I don't want to look at Mr. Bateman's fish. And I certainly don't want to read. I just want to get this meeting over with before I cry and make a fool of myself.

Mr. Bateman's office is huge. It's also dark. The blinds are closed and half the fluorescent lights are burned out. Aside from the lamp on his desk, most of the light in the room comes from the aquarium. That's fine, I guess. The darkness hides the junk piled in the corners: hammers, boards, paint cans, saws, boxes of nails, and a stepladder. Mr. Bateman renovated the place six months ago, but he hasn't tidied up yet.

Before the renovations, Bateman's Eternal Light didn't do funerals. It was a building supply center. That's why it's located between a lumber yard and a place that rents cement mixers. Mr. Bateman opened it when he arrived from England eight years ago. It was always busy, but these days, despite the building boom, there's more money in death than construction.

The day of the grand reopening, Mr. Bateman announced plans to have a chain of Eternal Lights across the country within two years. When reporters asked if he had any training in embalming, he said no, but he was completing a correspondence course from some college in the States. He also promised to hire the best hair stylists in town, and to offer discount rates. "No matter how poor, there's a place for everyone at Bateman's."

That's why I'm here.

When Mr. Bateman finally comes in, I don't notice. Somehow I've ended up on a folding chair in front of his aquarium staring at an angelfish. It's staring back. I wonder what it's thinking. I wonder if it knows it's trapped in a tank for the rest of its life. Or maybe it's happy swimming back and forth between the plastic grasses, nibbling algae from the turquoise pebbles and investigating the little pirate chest with the lid that blows air bubbles. I've loved angelfish ever since I saw pictures of them in a collection of National Geographies some missionaries donated to my school.

"So sorry to have kept you," Mr. Bateman says.

I leap to my feet.

"Sit, sit. Please," he smiles.

We shake hands and I sink back into the folding chair. He sits opposite me in an old leather recliner. There's a tear on the armrest with gray stuffing poking out. Mr. Bateman picks at it.

"Are we expecting your papa?"

"No," I say. "My step-papa's working." That's a lie. My step-papa is dead drunk at the neighborhood shebeen.

"Are we waiting for your mama, then?"

"She can't come either. She's very sick." This part is almost true. Mama is curled up on the floor, rocking my sister. When I told her we had to find a mortuary she just kept rocking. "You go," she whispered. "You're sixteen. I know you'll do what needs doing. I have to stay with my Sara."

Mr. Bateman clears his throat. "Might there be an auntie coming, then? Or an uncle?"

"No."

"Ah." His mouth bobs open and shut. His skin is pale and scaly. He reminds me of one of his fish. "Ah," he says again. "So you've been sent to make the arrangements by yourself."

I nod and stare at the small cigarette burn on his lapel. "I'm sixteen."

"Ah." He pauses. "How old was your sister?"

"Sara's one and a half," I say. "Was one and a half."

"One and a half. My, my." Mr. Bateman clucks his tongue. "It's always a shock when they're infants."

A shock? Sara was alive two hours ago. She was cranky all night because of her rash. Mama rocked her through dawn, till she stopped whining. At first we thought she'd just fallen asleep. (God, please forgive me for being angry with her last night. I didn't mean what I prayed. Please let this not be my fault.)

I lower my eyes.

Mr. Bateman breaks the silence. "You'll be glad you chose Eternal Light," he confides. "It's more than a mortuary. We provide embalming, a hearse, two wreaths, a small chapel, funeral programs and a mention in the local paper."

I guess this is supposed to make me feel better. It doesn't. "How much will it cost?" I ask.

"That depends," Mr. Bateman says. "What sort of funeral would you like?"

My hands flop on my lap. "Something simple, I guess."

"A good choice."

I nod. It's obvious I can't pay much. I got my dress from a ragpicker at the bazaar, and I'm dusty and sweaty from my bicycle ride here.

"Would you like to start by selecting a coffin?" he asks.

"Yes, please."

Mr. Bateman leads me to his showroom. The most expensive coffins are up front, but he doesn't want to insult me by whisking me to the back. Instead I get the full tour. "We stock a full line of products," he says. "Models come in pine and mahogany, and can be fitted with a variety of brass handles and bars. We have beveled edges, or plain. As for the linings, we offer silk, satin, and polyester in a range of colors. Plain pillowcases for the head rest are standard, but we can sew on a lace ribbon for free."

The more Mr. Bateman talks, the more excited he gets, giving each model a little rub with his handkerchief. He explains the difference between coffins and caskets: "Coffins have flat lids. Caskets have round lids." Not that it makes a difference. In the end, they're all boxes.

I'm a little frightened. We're getting to the back of the show-room and the price tags on the coffins are still an average year's wages. My step-papa does odd jobs, my mama keeps a few chickens and a vegetable garden, my sister is five and a half, my brother is four, and I'm in high school. Where is the money going to come from?

Mr. Bateman sees the look on my face. "For children's funerals, we have a less costly alternative," he says. He leads me behind a curtain into a back room and flicks on a light bulb. All around me, stacked to the ceiling, are tiny whitewashed coffins, dusted with yellow, pink, and blue spray paint.

Mr. Bateman opens one up. It's made of pressboards, held together with a handful of finishing nails. The lining is a plastic sheet, stapled in place. Tin handles are glued to the outside; if you tried to use them, they'd fall off.

I look away.

Mr. Bateman tries to comfort. "We wrap the children in a beautiful white shroud. Then we fluff the material over the sides of the box. All you see is the little face. Sara will look lovely."

I'm numb as he takes me back to the morgue, where she'll be kept till she's ready. He points at a row of oversized filing cabinets. "They're clean as a whistle, and fully refrigerated," he assures me. "Sara will have her own compartment, unless other children are brought in, of course, in which case she'll have to share."

We return to the office and Mr. Bateman hands me a contract. "If you've got the money handy, I'll drive by for the body at one. Sara will be ready for pickup Wednesday afternoon. I'll schedule the burial for Thursday morning."

I swallow hard. "Mama would like to hold off until the weekend. Our relatives need time to come in from the country."

"I'm afraid there's no discount on weekends," Mr. Bateman says, lighting a cigarette.

"Then maybe next Monday, a week today?"

"Not possible. I'll be up to my ears in new customers. I'm sorry. There're so many deaths these days. It's not me. It's the market."

An die Nachgeborenen / To Those Who Follow in Our Wake, Bertolt Brecht, 1939 (?).

[Follow the link to the source for the original German.]

I

Truly, I live in dark times!

An artless word is foolish. A smooth forehead

Points to insensitivity. He who laughs

Has not yet received

The terrible news.

What times are these, in which

A conversation about trees is almost a crime

For in doing so we maintain our silence about so much wrongdoing!

And he who walks quietly across the street,

Passes out of the reach of his friends

Who are in danger?

It is true: I work for a living

But, believe me, that is a coincidence. Nothing

That I do gives me the right to eat my fill.

By chance I have been spared. (If my luck does not hold, I am lost.)

They tell me: eat and drink. Be glad to be among the haves!

But how can I eat and drink

When I take what I eat from the starving

And those who thirst do not have my glass of water?

And yet I eat and drink.

I would happily be wise.

The old books teach us what wisdom is:

To retreat from the strife of the world

To live out the brief time that is your lot

Without fear

To make your way without violence

To repay evil with good –

The wise do not seek to satisfy their desires,

But to forget them.

But I cannot heed this:

Truly I live in dark times!

II

I came into the cities in a time of disorder

As hunger reigned.

I came among men in a time of turmoil

And I rose up with them.

And so passed

The time given to me on earth.

I ate my food between slaughters.

I laid down to sleep among murderers.

I tended to love with abandon.

I looked upon nature with impatience.

And so passed

The time given to me on earth.

In my time streets led into a swamp.

My language betrayed me to the slaughterer.

There was little I could do. But without me

The rulers sat more securely, or so I hoped.

And so passed

The time given to me on earth.

The powers were so limited. The goal

Lay far in the distance

It could clearly be seen although even I

Could hardly hope to reach it.

And so passed

The time given to me on earth.

III

You, who shall resurface following the flood

In which we have perished,

Contemplate –

When you speak of our weaknesses,

Also the dark time

That you have escaped.

For we went forth, changing our country more frequently than our shoes

Through the class warfare, despairing

That there was only injustice and no outrage.

And yet we knew:

Even the hatred of squalor

Distorts one’s features.

Even anger against injustice

Makes the voice grow hoarse. We

Who wished to lay the foundation for gentleness

Could not ourselves be gentle.

But you, when at last the time comes

That man can aid his fellow man,

Should think upon us

With leniency.

Men in Dark Times Preface, Hannah Arendt, 1968.

PREFACE

WRITTEN over a period of twelve years on the spur of occasion or opportunity, this collection of essays and articles is primarily concerned with persons — how they lived their lives, how they moved in the world, and how they were affected by historical time. The people assembled here could hardly be more unlike each other, and it is not difficult to imagine how they might have protested, had they been given a voice in the matter, against being gathered into a common room, as it were. For they have in common neither gifts nor convictions, neither profession nor milieu; with one exception, they hardly knew of each other. But they were contemporaries, though belonging to different generations — except, of course, for Lessing, who, however, in the introductory essay is treated as though he were a contemporary. Thus they share with each other the age in which their life span fell, die world during the first half of the twentieth century with its political catastrophes, its moral disasters, and its astonishing development of the arts and sciences. And while this age killed some of them and determined the life and work of others, there are a few who were hardly affected and none who could be said to be conditioned by it Those who are on the lookout for representatives of an era, for mouthpieces of the

Zeitgeist, for exponents of History (spelled with a capital H) will look here in vain.

Still, the historical time, the "dark times" mentioned in the title, is, I think, visible everywhere in this book. I borrow the term from Brecht's famous poem "To Posterity," which mentions the disorder and the hunger, the massacres and the slaughterers, the outrage over injustice and the despair "when there was only wrong and no outrage," the legitimate hatred that makes you ugly nevertheless, the well-founded wrath that makes the voice grow hoarse. All this was real enough as it took place in public; there was nothing secret or mysterious about it. And still, it was by no means visible to all, nor was it at all easy to perceive it; for, until the very moment when catastrophe overtook everything and everybody, it was covered up not by realities but by the highly efficient talk and double-talk of nearly all official representatives who, without interruption and in many ingenious variations, explained away unpleasant facts and justified concerns. When we think of dark times and of people living and moving in diem, we have to take this camouflage, emanating from and spread by "the establishment" — or "the system," as it was then called — also into account. If it is the function of the public realm to throw light on the affairs of men by providing a space of appearances in which they can show in deed and word, for better and worse, who they are and what they can do, then darkness has come when this light is extinguished by "credibility gaps" and "invisible government," by speech that does not disclose what is but sweeps it under the carpet, by exhortations, moral and otherwise, that, under the pretext of upholding old truths, degrade all truth to meaningless triviality.

Nothing of this is new. These are the conditions which, thirty years ago, were described by Sartre in

La Nausée (which I think is still his best book) in terms of bad faith and

l'esprit de sérieux, a world in which everybody who is publicly recognized belongs among the

salauds, and everything that is exists in an opaque, meaningless thereness which spreads obfuscation and causes disgust. And these are the same conditions which, forty years ago (though for altogether different purposes), Heidegger described with uncanny precision in those paragraphs of

Being and Time that deal with "the they," their "mere talk," and, generally, with everything that, unhidden and unprotected by the privacy of the self, appears in public. In his description of human existence, everything that is real or authentic is assaulted by the overwhelming power of "mere talk" that irresistibly arises out of the public realm, determining every aspect of everyday existence, anticipating and annihilating the sense or the nonsense of everything the future may bring. There is no escape, according to Heidegger, from the "incomprehensible triviality" of this common everyday world except by withdrawal from it into that solitude which philosophers since Parmenides and Plato have opposed to the political realm. We are here not concerned with the philosophical relevance of Heidegger's analyses (which, in my opinion, is undeniable) nor with the tradition of philosophic thought that stands behind them, but exclusively with certain underlying experiences of the time and their conceptual description. In our context, the point is that the sarcastic, perverse-sounding statement,

Das Licht der Öffentlichkeit verdunkelt alles ("The light of the public obscures everything"), went to the very heart of the matter and actually was no more than the most succinct summing-up of existing conditions.

"Dark times," in the broader sense I propose here, are as such not identical with the monstrosities of this century which indeed are of a horrible novelty. Dark times, in contrast, are not only not new, they are no rarity in history, although they were perhaps unknown in American history, which otherwise has its fair share, past and present, of crime and disaster. That even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination, and that such illumination may well come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and their works, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time span that was given them on earth — this conviction is the inarticulate background against which these profiles were drawn. Eyes so used to darkness as ours will hardly be able to tell whether their light was the light of a candle or that of a blazing sun. But such objective evaluation seems to me a matter of secondary importance which can be safely left to posterity.

January 1968

The Heart Determines: Psalm 73 Martin Buber, 1968.

MARTIN BUBER

The Heart Determines:

Psalm 73What is remarkable about this poem — composed of descriptions, of a story, and of confessions — is that a man tells how he reached the true meaning of his experience of life, and that this meaning borders directly on the eternal. For the most part we understand only gradually the decisive experiences we have in our relation with the world. First we accept what they seem to offer us, we express it, we weave it into a "view," and then think we are aware of our world. But we come to see that what we look on in this view is only an appearance. Not that our experiences have deceived us. But we had turned them to our use, without penetrating to their heart. What is it that teaches us to penetrate to their heart? Deeper experience.

The man who speaks in this psalm tells us how he penetrated to the heart of a weighty group of experiences — those experiences that show that the wicked prosper.

Apparently, then, the question is not what was the real question for Job — why the good do not prosper — but rather its obverse, as we find it most precisely, and probably for the first time, expressed in

Jeremiah (12:1): "Why does the way of the wicked prosper?"

Nevertheless, the psalm begins with a prefatory sentence in which, rightly considered, Job's question may he found hidden.

This sentence, the foreword to the psalm, is

Surely, God is good to Israel:

To the pure in heart.

It is true that the Psalmist is here concerned not with the happiness or unhappiness of the person, but with the happiness or unhappiness of Israel. But the experience behind the speeches of Job, as is evident in many of them, is itself not merely personal, but is the experience of Israel's suffermi!; both in the catastrophe that led to the Babylonian exile and in the beginning of the exile itself. Certainly only one who had plumbed the depths of personal suffering could speak in this way. But the speaker is a man of Israel in Israel's bitter hour of need, and in his personal suffering the suffering of Israel has been concentrated, so that what he now has to suffer he suffers as Israel. In the destiny of an authentic person the destiny of his people is gathered up, and only nnow becomes truly manifest.

Thus the Psalmist, whose theme is the fate of the person, also begins with the fate of Israel. Behind his opening sentence lies the question "Why do things go badly with Israel?" And first he answers, "Surely, God is good to Israel," and then he adds, by way of explanation, "to the pure in heart."

On first glance this seems to mean that it is only to the impure in Israel that God is not good. He is good to the pure in Israel; they are the "holy remnant," the true Israel, to whom He is good. But that would lead to the assertion that things go well with this remnant, and the questioner had taken as his starting point the experience that things went ill with Israel, not excepting indeed this part of it. The answer, understood in this way, would be no answer.

We must go deeper in this sentence. The questioner had drawn from the fact that things go ill with Israel the conclusion that therefore God is not good to Israel. But only one who is not pure in heart draws such a conclusion. One who is pure in heart, one who becomes pure in heart, cannot draw any such conclusion. For he experiences that God is good to him. But this does not mean that God rewards him with his goodness. It means, rather, that God's goodness is revealed to him who is pure in heart: he experiences this goodness. Insofar as Israel is pure in heart, becomes pure in heart, it experiences God's goodness.

Thus the essential dividing line is not between men who sin and men who do not sin, but between those who are pure in Heart and those who are impure in heart. Even the sinner whose heart becomes pure experiences God's goodness as it is revealed to him. As Israel purifies its heart, it experiences that God is good to it.

It is from this standpoint that everything that is said in the psalm about "the wicked" is to be understood. The "wicked" are those who deliberately persist in impurity of heart.

The state of the heart determines whether a man lives in the truth, in which God's goodness is experienced, or in the semblance of truth, where the fact that it "goes ill" with him is confused with the illusion that God is not good to him.

The state of the heart determines. That is why "heart" is the dominant key word in this psalm, and recurs six times.

And now, after this basic theme has been stated, the speaker begins to tell of the false ways in his experience of life.

Seeing the prosperity of "the wicked" daily and hearing their braggart speech has brought him very near to the abyss of despairing unbelief, of the inability to believe any more in a living God active in life. "But I, a little more and my feet had turned aside, a mere nothing and my steps had stumbled." He goes so far as to be jealous of "the wicked" for their privileged position.

It is not envy that he feels, it is jealousy, that it is

they who are manifestly preferred by God. That it is Indeed they is proved to him by their being sheltered from destiny. For them there are not

1, as for all the others, those constraining and confining "bands" of destiny; "they are never in the trouble of man." And so they deem themselves superior to all, and stalk around with their "sound and fat bellies," and when one looks in their eyes, which protrude from the fatness of their faces, one sees "the paintings of the heart," the wish-images of their pride and their cruelty, flitting across. Their relation to the world of their fellow men is arrogance and cunning, craftiness and exploitation. "They speak oppression from above" and "set their mouth to the heavens." From what is uttered by this mouth set to the heavens, the Psalmist quotes two characteristic sayings which were supposed to be familiar. In the one (introduced by "therefore," meaning "therefore they say") they make merry over God's relation to "His people." Those who speak are apparently in Palestine as owners of great farms, and scoff at the prospective return of the landless people from exile, in accordance with the prophecies: the prophet of the Exile has promised them water

(Isa. 41:l7f.), and "they may drink their fill of water," they will certainly not find much more here unless they become subject to the speakers. In the second saying they are apparently replying to the reproaches leveled against them: they were warned that God sees and knows the wrongs they have done, hut the God of heaven has other things to do than to concern Himself with such earthly matters: "How does God know? Is there knowledge in the Most High?" And God's attitude confirms them, those men living in comfortable security: "they have reached power," theirs is the power.

That was the first section of the psalm, in which the speaker depicted his grievous experience, the prosperity of the wicked. But now he goes on to explain how his understanding of this experience has undergone a fundamental change.

Since he had again and again to endure, side by side, his own suffering and their "grinning" well-being, he is overcome: "It is not fitting that I should make such comparisons, as my own heart is not pure." And he proceeded to purify it. In vain. Even when he succeeded in being able "to wash his hands in innocence" (which does not mean an action or feeling of self-righteousness, but the genuine, second and higher purity that is won by a great struggle of the soul), the torment continued, and now it was like a leprosy to him; and as leprosy is understood in the Bible as a punishment for the disturbed relation between heaven and earth, so each morning, after each pain-torn night, it came over the Psalmist — "It is a chastisement — why am I chastised?" And once again there arose the contrast between the horrible enigma of the happiness of the wicked and his suffering.

At this point he was tempted to accuse God as Job did. He felt himself urged to "tell how it is." But he fought and conquered the temptation. The story of this conquest follows in the most vigorous form that the speaker has at his disposal, as an appeal to God. He interrupts his objectivized account and addresses God. If I had followed my inner impulse, he says to Him, "I should have betrayed the generation of Thy sons." The generation of the sons of God! Then he did not know that the pure in heart are the children of God; now he does know. He would have betrayed them if he had arisen and accused God! For they continue in suffering and do not complain. The words sound to us as though the speaker contrasted these "children of God" with Job, the complaining "servant of God."

He, the Psalmist, was silent even in the hours when the conflict of the human world burned into his purified heart. But now he summoned every energy of thought in order to "know" the meaning of this conflict. He strained the eyes of the spirit in order to penetrate the darkness that hid the meaning from him. But he always percceived only the same conflict evere anew, and this perception itself seemed to him now to be a part of that "trouble" which lies on all save those "wicked" men—even on the pure in heart. He had become one of these, yet he still did not recognize that "God is good to Israel."

"Until I came into the sanctuaries of God. "Here the real turning point in this exemplary life is reached.

The man who is pure in heart, I said, experiences that God is good to him. He does not experience it as a consequence of the purification of his heart, but because only as one who is pure in heart is he ahle to come to the sanctuaries. This does not mean the Temple precincts in Jerusalem, but the sphere of God's holiness, the holy mysteries of God. Only to him who draws near to these is the true meaning of the conflict revealed.

But the true meaning of the conflict, which the Psalmist expresses here only for the other side, the "wicked," as he expressed it in the opening words for the right side, for the "pure in heart," is not — as the reader of the following words is only too easily misled into thinking — that the present state of affairs is replaced by a future state of affairs of a quite different kind, in which "in the end" things go well with the good and badly with the had; in the language of modern thought the meaning is that the bad do not truly exist, and their "end" brings about only this change, that they now inescapably experience their nonexistence, the suspicion of which they had again and again succeeded in dispelling. Their life was "set in slippery places"; it was so arranged as to slide into the knowledge of their own nothingness; and when this finally happens, "in a moment," the great terror falls upon them and they are consumed with terror. Their life has been a shadow structure in a dream of God's. God awakes, shakes off the dream, and disdainfully watches the dissolving shadow image.

This insight of the Psalmist, which he obtained as he drew near to the holy mysteries of God, where the conflict is resolved, is not expressed in the context of his story, but in an address to "his Lord." And in the same address he confesses, with harsh self-criticism, that at the same time the state of error in which he had lived until then and from which he had suffered so much was revealed to him: "When my heart rose up in me, and I was pricked in my reins, brutish was I and ignorant, I have been as a beast before Thee."

With this "before Thee" the middle section of the psalm significantly concludes, and at the end of the first line of the last section (after the description and the story comes the confession) the words are significantly taken up. The words "And I am" at the beginning of the verse are to he understood emphatically: "Nevertheless I am," "Nevertheless I am continually with Thee." God does not count it against the heart that has become pure that it was earlier accustomed "to rise up." Certainly even the erring and struggling man was "with Him," for the man who struggles for God is near Him even when he imagines that he is driven far from God. That is the reality we learn from the revelation to Job out of the storm, in the hour of Job's utter despair

(30:20-22) and utter readiness

(31:35-39). But what the Psalmist wishes to teach us, in contrast to the Book of Job, is that the fact of his being with God is revealed to the struggling man in the hour when — not led astray by doubt and despair into treason, and become pure In heart — "he comes to the sanctuaries of God." Here he receives the revelation of the "continually." He who draws near with a pure heart to the divine mystery learns that he is continually with God.

It is a revelation. It would be a misunderstanding of the whole situation to look on this as a pious feeling. From man's side there is no continuity, only from God's side. The Psalmist has learned that God and he are continually with one another. But he cannot express his experience as a word of God. The teller of the primitive stories made God say to the fathers and to the first leaders of the people: "I am with thee," and the word "continually" was unmistakably heard as well. Thereafter, this was no longer reported, and we hear it again only in rare prophecies. A Psalmist

(23:5) is still able to say to God: "Thou art with me." But when

Job (29: 5) speaks of God's having been with him in his youth, the fundamental word, the "continually," has disappeared. The speaker in our psalm is the first and only one to insert it expressly. He no longer says: "Thou art with me," but "I am continually with Thee." It is not, however, from his own consciousness and feeling that he can say this, for no man is able to be continually turned to the presence of God: he can say it only in the strength of the revelation that God is continually with him.

The Psalmist no longer dares to express the central experience as a word of God; but he expresses it by a gesture of God. God has taken his right hand—as a father, so we may add, in harmony with that expression "the generation of Thy children," takes his little son by the hand in order to lead him. More precisely, as in the dark a father takes his little son by the hand, certainly in order to lead him, but primarily in order to make present to him, in the warm touch of coursing blood, the fact that he, the father, is continually with him.

It is true that immediately after this the leading itself is expressed: "Thou dost guide me with Thy counsel." But ought this to be understood as meaning that the speaker expects God to recommend to him in the changing situations of his life what he should do and what he should refrain from doing? That would mean that the Psalmist believes that he now possesses a constant oracle, who would exonerate him from the duty of weighing up and deciding what he must do. Just because I take this man so seriously I cannot understand the matter in this way. The guiding counsel of God seems to me to he simply the divine Presence communicating itself direct to the pure in heart. He who is aware of this Presence acts in the changing situations of his life differently from him who does not perceive this Presence. The Presence acts as counsel: God counsels by making known that He is present. He has led His son out of darkness into the light, and now he can walk in the light. He is not relieved of taking and directing his own steps.

The revealing insight has changed life itself, as well as the meaning of the experience of life. It also changes the perspective of death. For the "oppressed" man death was only the mouth toward which the sluggish stream of suffering and truble flows. But now it has become the event in which God — the continually Present One, the One who grasps the man's hand, the Good One — "takes" a man.

The tellers of the legends had described the translation of the living Enoch and the living Elijah to heaven as "a being taken," a being taken away by God Himself. The Psalmists transferred the description from the realm of miracle to that of personal piety and its most personal expression. In a psalm that is related to our psalm not only in language and style but also in content and feeling, the

forty-ninth, there are these words: "But God will redeem my soul from the power of Sheol, when He takes me." There is nothing left here of the mythical idea of a translation. But not only that — there is nothing left of heaven either. There is nothing here about being able to go after death into heaven. And, so far as I see, there is nowhere in the "Old Testament" anything about this.

It is true that the sentence in our psalm that follows the words "Thou shall guide me with Thy counsel" seems to contradict this. It once seemed to me to be indeed so, when I translated it as "And afterwards Thou dost Cake me up to glory." But 1 can no longer maintain this interpretation. In the original text there are three words. The first, "afterwards," is unambiguous — "After Thou hast guided me with Thy counsel through the remainder of my life," that is, "at the end of my life." The second word needs more careful examination. For us who have grown up in the conceptual world of a later doctrine of immortality, it is almost self-evident that we should understand "Thou shah take me" as "Thou shalt take me up." The hearer or reader of that time understood simply, "Thou shalt take me away." But does the third word,

kabod, not contradict this interpretation? Does it not say

whither I shall be taken, namely, to "honor" or "glory"? No, it does not say this. We are led astray into this reading by understanding "taking up" instead of "taking."

This is not the only passage in the Scriptures where death and

kabod meet. In the song of Isaiah on the dead king of Babylon, who once wanted to ascend into heaven like the day Star, there are these words

(14:18): "All the kings of the nations, all of them, lie in

kabod, in glory, every one in his own house, but thou wert cast forth away from thy sepulcher." He is refused an honorable grave because he has destroyed his land and slain his people.

Kabod in death is granted to the others, because they have uprightly fulfilled the task of their life.

Kabod, whose root meaning is the radiation of the inner "weight" of a person, belongs to the earthly side of death. When I have lived my life, says our Psalmist to God, I shall die in

kabod, in the fulfillment of my existence. In my death the coils of Sheol will not embrace me, but Thy hand will grasp me. "For," as is said in another psalm related in kind to this one, the sixteenth, "Thou wilt not leave my soul to Sheol."

Sheol, the realm of nothingness, in which, as a later test explains

(Eccles. 9:10), there is neither activity nor consciousness, is not contrasted with a kingdom of heavenly bliss. But over against the realm of nothing there is God. The "wicked" have in the end a direct experience of their non-being; the "pure in heart" have in the end a direct experience of the Being of God.

This sense of

being taken is now expressed by the Psalmist in the unsurpassably clear cry, "Whom have I in heaven!" He does not aspire to enter heaven after death, fur God's home is not in heaven, so that heaven is empty. But he knows that in death he will cherish no desire to remain on earth, for now he will soon be wholly "with Thee" — here the word recurs for the third time — with Him who "has taken" him. But he does not mean by this what we are accustomed to call personal immortality, that is, continuation in the dimension of time so familiar to us in this our mortal life. He knows that after death "being with Him" will no longer mean, as it does in this life, "being separated from Him." 'I'he Psalmist now says with the strictest clarity what must now be said: it is not merely his flesh that vanishes in death, but also his heart, that inmost personal organ of the soul, which formerly "rose up" in rebellion against the human fate and which he then "purified" till he became pure in heart — this personal soul also vanishes. But He who was the true part and true fate of this person, the "rock" of this heart, God, is eternal. It is into His eternity that he who is pure in heart moves in death, and this eternity is something absolutely different from any kind of time.

Once again the Psalmist looks back at the "wicked," the thought of whom had once so stirred him. Now he does not call them the wicked, but "they that are far from Thee."

In the simplest manner he expresses what he has learned: since they are far from God, from Being, they are lost. And once more the positive follows the negative, once more, for the third and last time, that "and I," "and for me," which here means "nevertheless for me." "Nevertheless for me the good is to draw near to God." Here, in this conception of the good, the circle is closed. To him who may draw near to God, the good is given. To an Israel that is pure in heart the good is given, because it may draw near to God. Surely, God is good to Israel.

The speaker here ends his confession. But he does not yet break off. He gathers everything together. He has made his refuge, his "safety," "in his Lord" — he is sheltered in Him. And now, still turned to God, he speaks his last word about the task which is joined to all this, and which he has set himself, which God has set him — "To tell of all Thy works." Formerly he was provoked to tell of the

appearance, and he resisted. Now he knows, he has the

reality to tell of: the works of God. The first of his telling, the tale of the work that God has performed with him, is this psalm.

In this psalm two kinds of men seem to be contrasted with each other, the "pure in heart" and "the wicked." But that is not so. The "wicked," it is true, are clearly one kind of men, but the others are not. A man is as a "beast" and purifies his heart, and behold, God holds him by the hand. That is not a kind of men. Purity of heart is a state of being. A man is not pure in kind, but he is able to be or become pure—rather he is only essentially pure when he has become pure, and even then he does not thereby belong to a kind of men. The "wicked," that is, the bad, are not contrasted with good men. The good, says the Psalmist, is "to draw near to God." He does not say that those near to God are good. But he does call the bad "those who are far from God." In the language of modern thought that means that there are men who have no share in existence, but there are no men who possess existence. Existence cannot be possessed, but only shared in. One does not rest in the lap of existence, but one draws near to it. "Nearness" is nothing but such a drawing and coming near continually and as long as the human person lives.

The dynamic of farness and nearness is broken by death when it breaks the life of the person. With death there vanishes the heart, that inwardness of man, out of which arise the "pictures" of the imagination, and which rises up in defiance, but which can also be purified.

Separate souls vanish, separation vanishes. Time that has been lived by the soul vanishes with the soul; we know of no duration in time. Only die "rock" in which the heart is concealed, only the rock of human hearts, does not vanish. For it does not stand in time. The time of the world disappears before eternity, but existing man dies into eternity as into the perfect existence.

NOTE1. In what follows I read, as is almost universally accepted,

lama tam instead of

lemotam.

Down

This NYT Editorial seems like it's trying to be the 'soul of reason' (?) or are they portraying themselves as 'the honest witness' trying to make it clear? trying to make it plain? ... I can't make it out.

This NYT Editorial seems like it's trying to be the 'soul of reason' (?) or are they portraying themselves as 'the honest witness' trying to make it clear? trying to make it plain? ... I can't make it out.

These are games for the beach: drawing lines in the sand, circle tag, 'Fox & Hounds'. Or playing 'Marco Polo' in the swimming pool.

These are games for the beach: drawing lines in the sand, circle tag, 'Fox & Hounds'. Or playing 'Marco Polo' in the swimming pool.

At first it seemed as if Barack Obama would really stand up and tell it like it is. That's all he had to do. Anytime in his first two years as president would have been OK. Even now, maybe. Let's see what he does about the Keystone XL permit.

At first it seemed as if Barack Obama would really stand up and tell it like it is. That's all he had to do. Anytime in his first two years as president would have been OK. Even now, maybe. Let's see what he does about the Keystone XL permit.

Even to understanding the kind of box that executives at every level and position find themselves in.

Even to understanding the kind of box that executives at every level and position find themselves in.

No more than a couple of small-time (if over-weight) entrepreneurs, but with a clear mandate to cut costs (which everyone except a few naive socialists knows are over the top). So why would they cast themselves so unequivocally as bullies, churls, & stupid louts?

No more than a couple of small-time (if over-weight) entrepreneurs, but with a clear mandate to cut costs (which everyone except a few naive socialists knows are over the top). So why would they cast themselves so unequivocally as bullies, churls, & stupid louts?

"I've a feeling we're not in Kansas any more Toto." Well, no, it's Utah actually ... second on the left from Kansas (map).

"I've a feeling we're not in Kansas any more Toto." Well, no, it's Utah actually ... second on the left from Kansas (map).

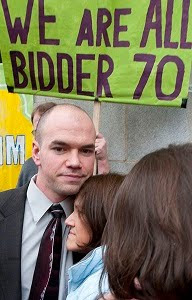

Tim DeChristopher's statement to the court is eloquent, clear, cool. The sleveens, Judge Dee Benson and prosecutor John Huber, not so much.

Tim DeChristopher's statement to the court is eloquent, clear, cool. The sleveens, Judge Dee Benson and prosecutor John Huber, not so much.

Their donate page doesn't seem to work, for Canadians at least, but I am guessing that cheques sent to:

Their donate page doesn't seem to work, for Canadians at least, but I am guessing that cheques sent to:

The judge seemed to think that a harsh sentence would deter others from getting involved or taking a similar path. He didn't get that right according to the twenty-six who were arrested immediately following his judgement for blocking the entrances to the court building (picture above) and the light-rail line on a nearby street (which included Chris Myers, a town councillor from Telluride).

The judge seemed to think that a harsh sentence would deter others from getting involved or taking a similar path. He didn't get that right according to the twenty-six who were arrested immediately following his judgement for blocking the entrances to the court building (picture above) and the light-rail line on a nearby street (which included Chris Myers, a town councillor from Telluride).

The point at which I decided to post all of this came when I read, "Only when she had been expelled from the land that for seventeen long years, supported by the money of her family, had permitted her to be Queen, Queen of fairies, did the truth dawn upon her," (on the one hand) and the end of the same paragraph, "In a way, that is how one feels when one reads on page after page about her 'successes' in later life and how she enjoyed them, magnifying them out of all proportion ..." (on the other).

The point at which I decided to post all of this came when I read, "Only when she had been expelled from the land that for seventeen long years, supported by the money of her family, had permitted her to be Queen, Queen of fairies, did the truth dawn upon her," (on the one hand) and the end of the same paragraph, "In a way, that is how one feels when one reads on page after page about her 'successes' in later life and how she enjoyed them, magnifying them out of all proportion ..." (on the other).

The process - of a story make an essence; of the essence make an elixir; and with the elixir begin once more to compound the story (with the caveat that "life itself is neither essence nor elixir") - seems to me to be common to the two of them, and to some other storytellers I have known.

The process - of a story make an essence; of the essence make an elixir; and with the elixir begin once more to compound the story (with the caveat that "life itself is neither essence nor elixir") - seems to me to be common to the two of them, and to some other storytellers I have known.

The 2nd & 3rd photographs come from an enigmatic blog I discovered along the way: The Eyes of the Pineapple. (There is an approximate Brazilian term 'descascar o abacaxi' / peel the pineapple, meaning solution of a difficult problem.)

The 2nd & 3rd photographs come from an enigmatic blog I discovered along the way: The Eyes of the Pineapple. (There is an approximate Brazilian term 'descascar o abacaxi' / peel the pineapple, meaning solution of a difficult problem.)

Malvados - Comics of the 10's: I found a heart in the trainee's desk. / He knows it's prohibited to bring your heart to work. / He's still just a boy, Gilberto. / But it's putting the bitterness of the older ones at risk.

Malvados - Comics of the 10's: I found a heart in the trainee's desk. / He knows it's prohibited to bring your heart to work. / He's still just a boy, Gilberto. / But it's putting the bitterness of the older ones at risk.

Last word goes to the scientists at Real Climate and their last word which is: "The bottom line is that there is NO merit whatsoever in this paper. It turns out that Spencer and Braswell have an almost perfect title for their paper: 'the misdiagnosis of surface temperature feedbacks from variations in the Earth’s Radiant Energy Balance' (leaving out the 'On')"