Up, Down, Appendices, Postscript.

This bit has to be first so the logo can be up-front.

This bit has to be first so the logo can be up-front.Despite a few naïvetés, the worst being apparently flattered by praise from the likes of Michael Moore, the energy does seem to be building around STOP HARPER!

I lay in bed the other night dreaming of papering the town with sticky replicas of Brigette DePape's artwork: every telephone pole, every streetcar seat, every subway window, every car bumper ... and most days I can barely walk.

This is a good idea too - a small easily made stencil can quickly turn every stop sign more ... eloquent, elegant & ... efficacious(?)

This is a good idea too - a small easily made stencil can quickly turn every stop sign more ... eloquent, elegant & ... efficacious(?)Brigett has set up a fund:

And she has published a piece in The (Toronto) Star.

That she could be called contemptuous, when it is Stephen Harper and his Government who are truely and officially in contempt of Parliament, is so silly ... it shows us all exactly where such voices are coming from. And the Lame tame Left Libs - L!L!L! - Bob Rae & Justin Trudeau & Elizabeth May (Raysie Justinne & Maysie, aka Flopsy Topsy & Mopsy) do not answer my emails asking (politely) for justification of their condemnation of this heroic girl.

As promised last week ... Chico Buarque is a smart guy, and with heart. In this tune he conflates past and present, and at the end, throws in the future too. In a way it is a song for that last line in Northrop Frye's The Double Vision:

"In the double vision of a spiritual and a physical world simultaneously present, every moment we have lived through we have also died out of into another order. Our life in the resurrection, then, is already here, and waiting to be recognized."

| João e Maria Agora eu era o herói E o meu cavalo só falava inglês A noiva do cowboy Era você além das outras três Eu enfrentava os batalhões Os alemães e seus canhões Guardava o meu bodoque E ensaiava o rock para as matinês Agora eu era o rei Era o bedel e era também juiz E pela minha lei A gente era obrigado a ser feliz E você era a princesa que eu fiz coroar E era tão linda de se admirar Que andava nua pelo meu país Não, não fuja não Finja que agora eu era o seu brinquedo Eu era o seu pião O seu bicho preferido Vem, me dê a mão A gente agora já não tinha medo No tempo da maldade Acho que a gente nem tinha nascido Agora era fatal Que o faz-de-conta terminasse assim Pra lá deste quintal Era uma noite que não tem mais fim Pois você sumiu no mundo Sem me avisar E agora eu era um louco a perguntar O que é que a vida vai fazer de mim? | Hansel and Gretel Now, I was the hero And my horse only spoke English The cowboy's bride Was you, along with three others I faced the battalions The Germans and their cannons I kept my bow And practiced rock for the matinées Now, I was the king It was the prefect and also the judge And by my law We had to be happy And you were the princess I crowned And it was so beautiful to admire you Who walked naked through my country No, don't run away, no Pretend that I am still your toy I was your spinning top Your favorite stuffed animal Come, give me your hand Now, We were still not afraid At the time of evil I think we had not even been born Now I know it was fatal That make-believe would end like this From this backyard to there Was a night that has no end Because you disappeared from the world Without telling me And now I was crazy enough to ask What will life do with me? |

I have been remembering old loves ... There I was in 1970, living in Paradise and didn't know any better than to abandon it the next year. Ai ai ai!

One evening as we walked up the hill and across the Stone Bridge, the moon was rising somewhere over Freshwater on the other side of the bay, huge and red it seemed to fill the sky ... I knew a man, he is dead now, who said of his middle-aged wife, "Ah, her breath is sweet ..."

Speaking of conflation we have ... lies, damned lies, & ... numbers.

Pick a number from 1-9. Multiply by 3. Add 3. Multiply by 3 again. Add the two digits together to find the number of the movie you are most likely to enjoy from this list:

| 1. The Graduate 2. Pierrot le fou 3. V For Vendetta 4. Doubt 5. To Kill A Mockingbird 6. The English Patient 7. Skin 8. The Collector 9. The Joy of Anal Sex With A Goat | 10. Casablanca 11. Rabbit-Proof Fence 12. Winters Bone 13. Wall-E 14. Bliss 15. Smilla's Sense Of Snow 16. Zabriskie Point 17. Miracle Mile 18. The Magus |

Clever huh? (If you didn't get 9 then you simply can't do mental arithmetic.)

OK, this is the meat of the matter this week, right here ... two books:

This is not going to be a comprehensive book review or anything. The question is: Who can you trust? Somewhere or other Northrop Frye praised Thomas Pynchon for 'the paranoid method' (see The Double Vision, Chapter 2):Collapse : how societies choose to fail or succeed by Jared Diamond, 2005, available at the Toronto Public Library or Abe's; and,

Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand by Haydn Washington & John Cook, not at the library for some reason, but described here. Don't buy it, wait for your library to catch up, for reasons to be explained.

"Thomas Pynchon's remarkable novel Gravity's Rainbow is a book that seems to me to have grasped a central principle of this situation. The human being, this novel tells us, is instinctively paranoid: We are first of all expressly convinced that the world was made for us and designed in detail for our benefit and appreciation. As soon as we are afflicted by doubts about this, we plunge into the other aspect of paranoia, feel that our environment is absurd and alienating, and that we are uniquely accursed in being aware, unlike any other organism in nature, of our own approaching mortality. Pynchon makes it clear that this paranoia can be and is transformed into creative energy and becomes the starting point of everything that humanity has done in the arts and sciences."So, I am providing a few resources as I get to know these people a little better to see if I can trust them, that's all.

I read Jared Diamond's book, Collapse a year or so ago, but got tangled up in details - he doesn't quite deal with rats as a major cause of Easter Island deforestation and so on - and then I arrived at his Chapter 15: Big Businesses and the Environment: Different Conditions, Different Outcomes, read his whitewash greenwash on Chevron in Papua New Guinea, and was gobsmacked!

I read Jared Diamond's book, Collapse a year or so ago, but got tangled up in details - he doesn't quite deal with rats as a major cause of Easter Island deforestation and so on - and then I arrived at his Chapter 15: Big Businesses and the Environment: Different Conditions, Different Outcomes, read his whitewash greenwash on Chevron in Papua New Guinea, and was gobsmacked!Here's a longish video of a talk at TED in 2003, you can easily find others. It is canned, he has done it many times before in about the same words and gestures, all good.

I have now gone back and re-read his Easter Island story, and it is so well written! The man is a natural-born teacher; piss-pot hat, comb-over, funny beard and all - his lectures must be worth standing up for, and the story, viewed as a whole, washes.

How then to explain the Chevron bullshit? I simply can't believe that he believes it - lame eh? The quality of writing is off too - as if it is something-that-must-be-done, an unpleasant duty, maybe it was bought and paid for? But surely he doesn't need cash that badly?

There is a name for beards cut like that ... but I can't remember it?

In the end I can't say why he did it, don't know. My guess is that the notion that capitalism is going to somehow save the day is like the notion that nuclear energy is going to save the day: adopted when all other apparent alternatives have been un-proven; adopted because it somehow nicely fits the narrative, and because you have to say something.

There was controversy in 2008 around Jared Diamond; has to be said because it is similar to the Colin Turnbull fabrication in ways ... you can find out about it if you want to beginning with Diamond's concocted (?) story in Atlantic ... no The New Yorker, Vengeance Is Ours: What can tribal societies tell us about our need to get even?: abstract ... and here is the complete thing in pdf.

As for Collapse, I was going to post excerpts but the chapters are long and there are lots of cheap copies at Abe's. Get it - read it, well worth the time.

I had an email from Tainter on his verbatim recapitulation of Turnbull's Ik story. He claims not to be aware of the controversy, not to have read the papers (so I sent him copies which he has not responded to). Maybe he will read them, maybe not, but again I think the notion slipped in there simply because ... it somehow fits the narrative, completes the story in some sense 'properly', has been seamlessly welded into the canon of archetypes or the social imaginary or whatever you want to call it.

And Jared Diamond did write that chapter on Chevron, so there is a bottom line to it.

The other one, Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand, is like a greasy lump of hair & nail-clippings blocking the J-trap in the sink. Very irritating that they have not built on Clive Hamilton's promising ideas, and have instead produced a poorly written, grossly over-footnoted, entirely unstructured right from the micro- to the macro-level, and sophomoric in the extreme, load of clap-trap ... What's in it is true of course, but ... Bleah! A veritable hair-ball of a book!

The other one, Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand, is like a greasy lump of hair & nail-clippings blocking the J-trap in the sink. Very irritating that they have not built on Clive Hamilton's promising ideas, and have instead produced a poorly written, grossly over-footnoted, entirely unstructured right from the micro- to the macro-level, and sophomoric in the extreme, load of clap-trap ... What's in it is true of course, but ... Bleah! A veritable hair-ball of a book! It is a problem because such books as this could be capable of drawing people in, convincing them - which in my experience here in Toronto is not happening, everywhere I go I see the same pundits and adherents. This book is probably being read by the choir and trilled about to those who are already convinced.

It is a problem because such books as this could be capable of drawing people in, convincing them - which in my experience here in Toronto is not happening, everywhere I go I see the same pundits and adherents. This book is probably being read by the choir and trilled about to those who are already convinced.Anyway, that's it - count me out of the choir; I am not going to buy anymore of these books. Dumb & Dumber and Cheech & Chong are okay if you are drunk or stoned enough, but no more of this dreck & drivvle, not on my nickle! ... either they will come to the library eventually and I will see them then, or I will give them a miss.

Naomi Oreskes' excellent preface is the only part worth saving; and a précis too, almost; so I have reproduced it below. I am surprised she lent her name to this book? I can't believe she read it. She calls it a 'fine book' - incredible!

Naomi Oreskes' excellent preface is the only part worth saving; and a précis too, almost; so I have reproduced it below. I am surprised she lent her name to this book? I can't believe she read it. She calls it a 'fine book' - incredible!The editing is patchy as well ... maybe, what with EarthScan changing hands, the editors just let this one fall through a crack. Even Oreskes' preface has at least two typos.

No cheap copies of her other one around, if that's any indication ... Merchants of doubt: how a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming with Erik Conway, 2010.

Too harsh by half ... Naomi Oreskes' essay did make it worthwhile.

Too harsh by half ... Naomi Oreskes' essay did make it worthwhile.Here, get to know her a bit better: at York University last fall with a video. The 5 min introduction is interesting too ... what you have to put up with in the way of academic politics ... the guy seems to think that nuclear war is on a par with climate change (Doh!?)

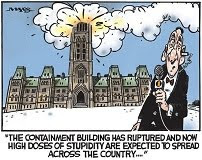

She used that New Yorker cartoon to end one of her presentations, and I liked it.

Addendum: A post at ClimateInsight around some of the issues raised by Naomi.

Just wondering eh? ... (as I have wondered a few times recently: here here & here) There is no connection of course between: Lady Gaga promoting a 10 year-old Maria Aragon (who has taken full advantage); and Rihanna's performance in Toronto last week; and the daughter of an hispanic ex-carpenter, Juan & his wife who was raped by 19 black men in Cleveland Texas; and the SlutWalks being promoted in a fury of correctitude because Michael Sanguinetti, a Toronto cop (who has now been sent away for 're-education') had the temerity to suggest a connection between the way you look and your likelihood of being raped. Doh!?

Just wondering eh? ... (as I have wondered a few times recently: here here & here) There is no connection of course between: Lady Gaga promoting a 10 year-old Maria Aragon (who has taken full advantage); and Rihanna's performance in Toronto last week; and the daughter of an hispanic ex-carpenter, Juan & his wife who was raped by 19 black men in Cleveland Texas; and the SlutWalks being promoted in a fury of correctitude because Michael Sanguinetti, a Toronto cop (who has now been sent away for 're-education') had the temerity to suggest a connection between the way you look and your likelihood of being raped. Doh!? And there is no connection between any of that and our arrogant & contemptuous Stephen Harper? No, of course not! It is arrogant & contemptuous to even think so!

And there is no connection between any of that and our arrogant & contemptuous Stephen Harper? No, of course not! It is arrogant & contemptuous to even think so!And yes, we had an election and the election is over and Harper threaded the needle, split the middle, and won a majority. Is that par for a complacent mediocrity of a bunch of bourgeois twits? I don't know enough history to say.

Here is what I will say: We have until about 2015 to turn CO2 and equivalent greenhouse gas emissions around or we are collectively cooked. Harper's majority will just be ending in 2015 - too late! So

Any way you decently can, gentle reader.

(My kids all figgure I will die by TASER anyway, an' I don't wanna disappoint 'em.)

(My kids all figgure I will die by TASER anyway, an' I don't wanna disappoint 'em.)Be well.

(Oops! Forgot the music ... this has been running through my head all week, from the movie Eu Tu Eles which is where I first heard it, and here he is, singing it last year in Rio, gettin' old but still gettin' on! É, né? Baião da Penha.)

Postscript:

Altino Machado interviewed Falb Saraiva de Farias: on video, and published articles here & here & here.

Altino Machado interviewed Falb Saraiva de Farias: on video, and published articles here & here & here. I sort'a wanted to make a transcript and translate it all, because here seems to be the story of a man who claims on the order of 50,000 square miles of the Amazon rain forest.

I sort'a wanted to make a transcript and translate it all, because here seems to be the story of a man who claims on the order of 50,000 square miles of the Amazon rain forest.That's right, miles, here, 12.7 million hectares, do the arithmetic; which, if it were all together and square, would be about 225 miles on a side - visible, as they say, from space.

Altino Machado gets high marks with me for this interview. He seems to hold himself in check without being in any degree false, in order to get the whole story. How rare is that? The resulting story contains much of what is necessary to understand Sr. Falb Saraiva de Farias, his history & development as a poor man in Brazil who made it big - he is arguably the biggest landowner in the world.

Altino Machado gets high marks with me for this interview. He seems to hold himself in check without being in any degree false, in order to get the whole story. How rare is that? The resulting story contains much of what is necessary to understand Sr. Falb Saraiva de Farias, his history & development as a poor man in Brazil who made it big - he is arguably the biggest landowner in the world.That's bigger than the entire island of Newfoundland at 43,000 square miles, dig it.

That these experienced and talented men can utter such meek bleats ... Rick Salutin & Paul Krugman ... it is as if they are capable of building a ramp to jump the Snake River Canyon, and they do build it, and then at the last instant they go off to the side and sit staring ...

OK, here it is, here's the next piece: Clive Hamilton and Naomi Oreskes get to the point of recognizing fear as the dominant feature of what underpins denialist positions. And it's good, it's close ... but we are not all cowards. We know about fear and have, each and every one of us to some degree, overcome it.

So why are we not taking up the obvious scientific truth of what is happening? It's because we don't trust scientists any more than we trust greed-head commerce and politicians. Mervyn Peake's Gormenghast is as good an example as any, or Lord of the Rings ... and the mythic nut of these stories points straight at the reality of what we have seen happen in our lives, and in the lives of the previous generation, explicitly, factually, concretely.

Who is the greatest scientist ever? Well ... Einstein, obviously. And what did his e=mc2 lead to? The atomic bomb. Nuclear energy. And it is the same right on up through genetically modified 'Roundup-Ready' soy beans. Even the petty stuff: cheaper and cheaper goods, less and less fit for human use or consumption, more and more pollution and waste; and where did all this shit come from? Scientists! And how did we have it delivered? Up the ass!

The Green Revolution? Borlaug the hero? Where did it lead us? To large numbers of Indian farmers standing in their fields drinking pesticide.

Yeah ... if some bodunk red neck doesn't want to be told what to do by scientists and their economic beneficiaries and political masters - I can dig it. In fact ... Me too!

Yeah but - this is different eh?! This is serious! And so it is. But for Naomi Oreskes to get the point across she is first going to have to acknowledge the actual history - and that is going to make it a very tough sell indeed.

That's one side of it; as for the other side, as for what is in the hearts of the Koch brothers, and Stephen Harper, and Tim Ball and Lawrence Solomon, and all the rest all of their troglodyte adherents?

Appendices:

1. Why I did it: Senate page explains her throne speech protest, Brigette DePape, June 8 2011.

2. The strange, and very political, death of hope, Rick Salutin, June 2 2011.

3. Rule by Rentiers, Paul Krugman, June 9 2011.

4. Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand Foreword, Naomi Oreskes, January 2011.

Why I did it: Senate page explains her throne speech protest, Brigette DePape, June 8 2011.

I am moved by the excitement and energy with which people from all walks of life across this country greeted my action in the Senate.

One person alone cannot accomplish much, but they must at least do what they can. So I held out my “Stop Harper” sign during the throne speech because I felt I had a responsibility to use my position to oppose a government whose values go against the majority of Canadians.

The thousands of positive comments shared online, the printing of “Stop Harper” buttons and stickers and lawn signs, and the many calls for further action convinced me that this is not merely a country of people dissatisfied with Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s vision for Canada.

It is a country of people burning with desire for change.

If I was able to do what I did, I know that there are thousands of others capable of equal, or far more courageous, acts.

I think those who reacted with excitement realize that politics should not be left to the politicians, and that democracy is not just about marking a ballot every few years. It is about ensuring, with daily engagement and resistance, that the vision we have for our society is reflected in the decision-making of our government.

Our views are not represented by our political system. How else could we have a government that 60 per cent of the people voted against? A broken system is what has left us with a Conservative government ready to spend billions on fighter jets we don’t need, to pollute the environment we want protected, to degrade a health-care system we want improved, and to cut social programs and public sector jobs we value. As a page, I witnessed one irresponsible bill after another pass through the Senate, and wanted to scream “Stop.”

Such a system leads us to feel isolated, powerless and hopeless — thousands of Canadians made that clear in their responses to my action. We need a reminder that there are alternatives. We need a reminder that we have both the capacity to create change, and an obligation to. If my action has been that reminder, it was a success.

Media and politicians have argued that I tarnished the throne speech, a solemn Canadian tradition. I now believe more in another tradition — the tradition of ordinary people in this country fighting to create a more just and sustainable world, using peaceful direct action and civil disobedience.

On occasion, that tradition has found an inspiring home within Parliament: In 1970, for instance, a group of young women chained themselves to the parliamentary gallery seats to protest the Canadian law that criminalized abortion. Their action won national attention, and helped propel a movement that eventually achieved abortion’s legalization.

Was such an action “appropriate”? Not in the conventional sense. But those women were driven by insights known to every social movement in history: that the ending of injustices or the winning of human rights are never gifts from rulers or from parliaments, but the fruit of struggle and of people power in the streets.

Actions like these provide the answer to the Harper government. When Harper tries to push through policies and legislation that hurt our communities and country, we all need to find our inner activist, and flow into the streets. And what is a stop sign after all, but a nod to the symbol of the street where a people amassed can put the brakes on the Harper government?

I’ve been inspired by Canadians taking action, and inspired too by my peers rising up in North Africa and the Middle East. I am honoured to have since received a message from young activists there, saying that we need not just an Arab spring but a “world spring,” using people power to combat whatever ills exists in each country.

I have been inspired most of all by Asmaa Mahfouz, the 26-year-old woman who issued a video calling for Egyptians to join her in Tahrir Square. People did, and they together made the Egyptian revolution. Her words will always stay with me: “As long as you say there is no hope, then there will be no hope, but if you go and take a stand, then there will be hope.”

The strange, and very political, death of hope, Rick Salutin, June 2 2011.

Hope is indispensable in public and private life. I don’t mean brainless optimism in the face of facts. I mean hope that finds a way to persist in honest awareness of how bad things are.

Take the economy. Everyone knows that the disaster of 2008, which has clearly not gone away, had nothing to do with excess government spending. It had/has to do with other things: loss of good jobs; wage stagnation; jumps in consumer debt to cover the losses; “financialization”; fraud; greed; lack of oversight — blah blah blah. Any rise in deficits came mainly from bailouts to banks, or needless warmaking. The point is: The catastrophe had/has no connection to government social or economic spending. Yet the only solutions proposed everywhere are public spending cuts.

Ordinary people know, or sense, that this is stupid. Even in the U.S., a poll this year found only 20 per cent thought deficit reduction validated cuts in pensions or medicare. Only 25 per cent would reduce education spending to balance the budget. Even public support to the arts had majority support. They have their heads screwed on; they know where the real problems are and aren’t.

But — and here’s where hope comes in, or flies out the door — governments slash anyway. Not just in crisis cases like Greece, Portugal and Spain. But in the U.S., U.K. and here, as we’re told to expect in next week’s budget. Please note that in many cases these pointless, unwarranted cuts are made by “left” governments. The three European governments all have “socialist” in their names. Barack Obama has joined the attack in the U.S.

What will the effect on people be? Cuts that they know are unjustified, and probably damaging, and which they often explicitly voted against — will be made. What is the point of voting, or even bothering to think about these matters? This is how hope in public participation dies, or is killed off.

Let me note a special Canadian role in this hopicide. I’m thinking of Paul Martin, finance minister in the Liberal Chrétien government of the 1990s. The Liberals rose to power promising to reconsider free trade, end the GST and give the country universal child care. They did none. Instead they focused obsessively on ending the deficit by slashing public programs. Martin went from year to year and program to program like one of the manic unsubs on Criminal Minds. At the end there was no hope left for government activity. When he finally became prime minister and tried to compensate with a bit of child care, it was hopelessly late. The voters turned him out.

Recently the Mercatus Center in the U.S. hailed Martin a hero and urged their own leaders to emulate him. In case you aren’t familiar with Mercatus, it’s a right wing think-tank funded by the far-right Koch brothers and dedicated to ending government activity wherever possible, including limits on truckers’ hours and on arsenic in drinking water. This will be Martin’s legacy: verbal monuments erected with right-wing U.S. money to the death of public hope.

Where do people turn when leaders and parties that promised to do what seemed to make sense, betray them? Either to despair or to themselves. That often means: into the streets, where the battles for democracy and justice frequently began. Take the encampments of “los indignados” in Spain. Who are they indignant at? The greedy rich, obviously. But also their gutless, lying, “left wing” politicians. Their manifestos basically demand that those parties do what they said they would: protect workers and academic freedom, extend social benefits, use non-nuclear energy, create proportional representation, etc.

What are their odds of success? Well, Spain does have a great anarchist (i.e., leaderless) tradition with many achievements. But eventually, at this stage of human evolution, you probably have to turn back to institutions of government, flawed as they are (like other flawed but seemingly unavoidable institutions: medicine, teaching, journalism . . .) Still, as a way to go, it beats those alternatives, apathy and despair.

Rule by Rentiers, Paul Krugman, June 9 2011.

The latest economic data have dashed any hope of a quick end to America’s job drought, which has already gone on so long that the average unemployed American has been out of work for almost 40 weeks. Yet there is no political will to do anything about the situation. Far from being ready to spend more on job creation, both parties agree that it’s time to slash spending — destroying jobs in the process — with the only difference being one of degree.

Nor is the Federal Reserve riding to the rescue. On Tuesday, Ben Bernanke, the Fed chairman, acknowledged the grimness of the economic picture but indicated that he will do nothing about it.

And debt relief for homeowners — which could have done a lot to promote overall economic recovery — has simply dropped off the agenda. The existing program for mortgage relief has been a bust, spending only a tiny fraction of the funds allocated, but there seems to be no interest in revamping and restarting the effort.

The situation is similar in Europe, but arguably even worse. In particular, the European Central Bank’s hard-money, anti-debt-relief rhetoric makes Mr. Bernanke sound like William Jennings Bryan.

What lies behind this trans-Atlantic policy paralysis? I’m increasingly convinced that it’s a response to interest-group pressure. Consciously or not, policy makers are catering almost exclusively to the interests of rentiers — those who derive lots of income from assets, who lent large sums of money in the past, often unwisely, but are now being protected from loss at everyone else’s expense.

Of course, that’s not the way what I call the Pain Caucus makes its case. Instead, the argument against helping the unemployed is framed in terms of economic risks: Do anything to create jobs and interest rates will soar, runaway inflation will break out, and so on. But these risks keep not materializing. Interest rates remain near historic lows, while inflation outside the price of oil — which is determined by world markets and events, not U.S. policy — remains low.

And against these hypothetical risks one must set the reality of an economy that remains deeply depressed, at great cost both to today’s workers and to our nation’s future. After all, how can we expect to prosper two decades from now when millions of young graduates are, in effect, being denied the chance to get started on their careers?

Ask for a coherent theory behind the abandonment of the unemployed and you won’t get an answer. Instead, members of the Pain Caucus seem to be making it up as they go along, inventing ever-changing rationales for their never-changing policy prescriptions.

While the ostensible reasons for inflicting pain keep changing, however, the policy prescriptions of the Pain Caucus all have one thing in common: They protect the interests of creditors, no matter the cost. Deficit spending could put the unemployed to work — but it might hurt the interests of existing bondholders. More aggressive action by the Fed could help boost us out of this slump — in fact, even Republican economists have argued that a bit of inflation might be exactly what the doctor ordered — but deflation, not inflation, serves the interests of creditors. And, of course, there’s fierce opposition to anything smacking of debt relief.

Who are these creditors I’m talking about? Not hard-working, thrifty small business owners and workers, although it serves the interests of the big players to pretend that it’s all about protecting little guys who play by the rules. The reality is that both small businesses and workers are hurt far more by the weak economy than they would be by, say, modest inflation that helps promote recovery.

No, the only real beneficiaries of Pain Caucus policies (aside from the Chinese government) are the rentiers: bankers and wealthy individuals with lots of bonds in their portfolios.

And that explains why creditor interests bulk so large in policy; not only is this the class that makes big campaign contributions, it’s the class that has personal access to policy makers — many of whom go to work for these people when they exit government through the revolving door. The process of influence doesn’t have to involve raw corruption (although that happens, too). All it requires is the tendency to assume that what’s good for the people you hang out with, the people who seem so impressive in meetings — hey, they’re rich, they’re smart, and they have great tailors — must be good for the economy as a whole.

But the reality is just the opposite: creditor-friendly policies are crippling the economy. This is a negative-sum game, in which the attempt to protect the rentiers from any losses is inflicting much larger losses on everyone else. And the only way to get a real recovery is to stop playing that game.

Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand Foreword, Naomi Oreskes, January 2011.

People who refuse to accept the scientific evidence of anthropogenic climate change like to call themselves skeptics. But as Haydn Washington and John Cook note in this straightforward and much-needed book, these men (and they are nearly all men) are not skeptics. A skeptic is a person who challenges his opponents to provide evidence for their beliefs. A skeptic rejects articles of faith and positions that defy refutation in the face of facts. In this sense, all scientists are skeptics. They insist that any claim be supported by evidence, and they insist on a substantial debate about the quantity and quality of that evidence before accepting it. The more radical the claim, the higher the bar to acceptance.

When Svante Arrhenius first suggested that increased atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels could lead to global climate change, it was a radical claim. Who in the late 19th century believed that human activities could match the scale of natural forces? In any case there was no way to test the idea. Arrhenius was making a prediction about something that could happen in the future, not a claim about something that was already happening.1

The first scientist to claim that climate change was under way was British engineer Guy Stuart Callendar [sic]. In the early 1930s Callendar compiled available global data (mostly in Europe), which suggested that both atmospheric carbon dioxide and average global temperatures were starting to rise. Other scientists addressed the issue theoretically. American physicist E. O. Hulburt, a physicist at the US Naval Research Laboratory, calculated the effect of doubling CO2 on global climate based on physical principles, and concluded that doubling CO2 would increase average global temperature by 4°C, while tripling would increase it by 7°C. This, he noted, this was sufficient to change Earth's climate dramatically.2

A lot has happened since the 1930s, and climate change is no longer a radical claim. In fact, it's not a 'claim' at all. It's an established scientific fact. In over 10,000 peer-reviewed scientific papers, as well as thousands of pages of summary produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), scientists have demonstrated that atmospheric CO2 has increased, and global temperature has increased too.3 As a result, spring is coming earlier than it used to. Rivers and lakes are warming. Glaciers are shrinking, while glacial lakes are expanding. Permafrost is becoming unstable. Plants and animals are shifting their ranges upwards in terms of both latitude and elevation.4 And extreme weather events - droughts, floods, hurricanes - are becoming a little bit more common, and a little bit more extreme.

While scientists knew for a long time that such changes could happen, it was only in the 1980s that they began to think that they surely would happen. In 1979, the US National Academy of Sciences wrote, 'If carbon dioxide continues to increase, the study group finds no reason to doubt that climate changes will result and no reason to believe that these changes will be negligible.'5

And that's when the denial began to set in ...

As Erik Conway and I wrote in our recent book, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco to Global Warming, almost as soon as the proverbial ink was dry on the National Academy report, some people began to challenge its conclusions. They did so for reasons that had very little to do with the science, and everything to do with politics and ideology.

In 1983, the Academy undertook a larger, more comprehensive report, chaired by conservative scientist William Nierenberg, who argued that the results of climate change would be negligible, because people were highly adaptable, and technological innovation, flourishing under free market conditions, would enable us to address any adverse impacts that arose. It was not an empirical argument - it was not based on evidence drawn from history, or sociology, or anthropology (indeed, there were no social scientists other than economists on the committee). It was an ideological argument, rooted in Nierenberg's anti-communism and commitment to free market principles.

Nierenberg was a Cold War scientist who had began his career working on the Manhattan Project - the crash programme to build an atomic bomb during World War II - and in the years that followed, he built a career close to the corridors of power. By the 1980s, he had ties to the administration of President Ronald Reagan, who favoured free market solutions to social problems. We know now, from historical research, that while Nierenberg was chairing the climate change committee, he was also appointed by the Reagan administration to review the scientific evidence of acid rain, and he altered the Executive Summary of that committee's report - under the guidance of White House science adviser George Keyworth - to make the problem of acid rain seem less urgent than the committee believed.

The very next year - 1984 - Nierenberg joined forces with two other politically conservative physicists - Robert Jastrow and Frederick Seitz - to create the George C. Marshall Institute, a think tank that would defend Reagan administration policies with respect to strategic defence and nuclear weaponry. Seitz was a former President of the Rockefeller University, with long-standing ties to the tobacco industry; Jastrow was an astrophysicist involved in the US space programme. By the end of the 1980s, Seitz, Jastrow and Nierenberg were challenging the evidence of global warming and the ozone hole. Their work laid the ground for a host of others - individuals, think tanks, private institutes and corporations - to launch a full-scale attack on climate science. Climate change denial began in the 1980s, and it continues to this day.

In the early 2000s, when I first begin to lecture about the history of climate science, I would be asked the same skeptical questions over and over again. 'What about the sun?' 'Isn't it true that warming has stopped?' 'Why should I believe a computer?' 'The climate has always been changing, so why should I worry?' And, less belligerently, 'Where can I go to get good clear answers to my questions?' I knew the answers to the first four questions, but there wasn't a good answer to the last one, and it was telling that the same questions came up over and over again. Clearly, scientists had not succeeded in communicating to the general public what they had long known, whereas skeptical claims had percolated into public consciousness.

As a university professor who competes daily with the internet for my students' attention, I understood the power of the web, and it frustrated me that scientists hadn't done more to use it. So I was happy indeed when I discovered John Cook's wonderful website, www.skepticalscience.com, which calmly and systematically debunks the most common 'denialist' arguments. When I discovered that Cook even had an iPhone app, I knew these were people I wanted to know.

For too long, scientists have debated climate science in the halls of science, thinking it was someone else's job to communicate the science to the rest of us. Meanwhile, vocal groups with an ideological or economic interest in challenging the scientific evidence did exactly that, in well-organized, well-funded and persistent campaigns. Many of the same groups and individuals who now challenge the scientific evidence of anthropogenic climate change previously challenged the evidence of tobacco smoking, acid rain and the ozone hole. Some have even tried to reopen the debate over DDT, claiming that DDT was never dangerous, and that millions of people have died unnecessarily from malaria because of the US decision to ban DDT in the United States.

Most of these claims are just false. The attempt to rehabilitate DDT, for example, is based on claims that are demonstrably erroneous. DDT does cause cancer; it was never the miracle chemical that its supporters claimed (and continue to claim); and the World Health Organization moved away from it in malaria prevention not because of environmental hysteria but because mosquitoes were developing resistance.6

Other 'denialist' claims have been shown to be incorrect as well - or at least to be misleading half-truths. Washington and Cook note that there are common patterns in the denial of scientific evidence: the most common is to claim that observed changes are natural variability. And if they are natural, then there is no cause for concern and no reason for change from 'business as usual'.

This can be hard to refute, because the natural world is highly variable. It is the job of scientists to sort out the diverse causes of natural change, to determine their magnitude and rate, and to differentiate them from human effects. What we know, after half a century of scientific work, is that the human footprint on the planet is now so large that human drivers of change are in many cases overwhelming natural drivers. There is natural climate variability - including changes caused by natural fluctuations in solar irradiance and atmospheric CO2 - but natural variability is being overridden by planetary warming dominated by human activity: the production of greenhouse gases and the destruction of forests, mangrove swamps, and other natural carbon sinks. Similarly, there is natural variability in stratospheric ozone, but the depletions observed in the 1980s were caused primarily by the synthetic chemicals known as chlorofluorocarbons. There is natural acidic rain, but it was vastly increased in the 20th century by pollution from coal-fired electrical utilities, smelters and automobiles.

How do denialists make such half-truths seem credible? By relying on scientists to make them. In the 1950s, tobacco industry executives realized that if they attacked the scientific evidence of the harms of their product, the conflict of interest would be obvious. But if scientists raised questions about the science, that would be a whole different matter. So they set out to find scientists who were willing to do just that.

We see the same pattern in the challenges to climate science. Washington and Cook directly address the recent claims of Ian Plimer, who has received enormous attention in Australia (where both authors of this book live) for his view that the observed increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide is caused by volcanoes, and that it doesn't matter anyway since 'you can double carbon dioxide and it has no effect'.7

These are very strange claims. Irish experimentalist John Tyndall first demonstrated in the 1850s that carbon dioxide was a powerful greenhouse gas, and that its presence in the atmosphere, even at extremely low concentrations, was crucial for Earth's benevolent climate. Since then numerous other studies have confirmed the high sensitivity of the planetary climate to atmospheric CO2. We've increased atmospheric CO2 by about one-third, and we've seen an increase in average global temperature already of just under 1°C. Climate sensitivity isn't just a theory, it's an observation.

As for the source of the recent increase in CO2, that was worked out in 2003 - and it's not volcanoes.8 Many of us know that there are two forms of carbon: ordinary C-12, and radioactive C-14, which is used to date archeological relics and other things. But there is a third kind of carbon, C-13, the concentration of which varies in natural reservoirs. Plants and materials derived from them, notably coal, have much lower concentrations of C-13 than other materials, including the CO2 emitted from volcanoes. Isotope geochemists Prosenjit Ghosh and Willi A. Brand measured the C-13 content of atmospheric CO2 and showed that as total CO2 rose, the C-13 content fell. This result is just what you'd expect if that CO2 came from fossil fuels.

Plimer speculates that invisible, undetected, underwater volcanoes are responsible for the increased atmospheric CO2. Besides the obvious point that he is asking us to believe in something that no one has seen, felt or observed in any form, he asks us to disbelieve what scientists have seen and measured. It's a bit like asking us to believe in Santa Claus after we have seen our parents putting the presents under the tree.

Plimer is a geologist, not a climate scientist, and as a former exploration geologist myself - who cut my teeth in the Australian mining industry -1 would never assume that a mining geologist is not a fine human being. But when it comes to judging a person's claims, it is reasonable to ask: Is this person actually an expert? And if his claims go against the conclusions of genuine experts, then why is he insisting on them? Indeed, why is he even involved in the debate at all? And why are we listening?

The answer to the questions above might simply be that Plimer's strong links to the mining industry may be influencing his views on the matter. While many business leaders accept the scientific evidence of anthropogenic climate change and see business opportunities in addressing it, those in the traditional business of extracting resources from the ground have been having a harder time. People fear change because they fear loss, and in doing something about climate change, there will be winners and losers. Hard rock mining will not necessarily lose - particularly mining for uranium for nuclear power, or materials necessary for solar cells or wind turbines - but the fossil fuel industry will lose, unless it moves briskly into new areas. Here we see the tobacco problem all over again. The tobacco industry was hugely profitable and its primary product was deadly. That was a serious difficulty. The industry did not respond well to it. The fossil fuel industry is repeating the pattern.

But if this is an old pattern, why are we falling for it?

Why Do Denialist Claims Persist?

Given that virtually every denialist claim of the past 20 years has been shown to have been misleading, or just plain false, why do these claims persist? Why do so many of us listen to them?

Most scientists think the problem is scientific illiteracy, so the solution is to get more information to more people. Climate modeller James Hansen, one of the first scientists to speak out publicly on the threat of unmitigated climate change (and one of the most passionate voices now calling for immediate action), has concluded that if the public had a better understanding of the climate crisis they would 'do what needed to be done'.9

Sadly, the evidence is against this conclusion. Scientists have been communicating what they know for a long time. The raison d'être of the IPCC - much maligned by climate deniers - was to communicate relevant science to governments and other interested parties. This information is readily available. But availability of information does not guarantee that people will accept it.10 In both the United States and Australia, many highly educated people have rejected the conclusions of climate science, including chairmen of the boards of leading corporations, members of US Congress, and even occupants of the American White House.

There are many reasons why people resist bad news, but it is clear that a major driver here is fear. Fear that our current way of life is unsustainable. Fear that addressing the issue will limit economic growth. Fear that if we accept government interventions in the market place - through a cap-and-trade system to control greenhouse gas emissions, a carbon tax, or some more severe approach - it will lead to a loss of personal freedom.

Or maybe just plain old fear of change. Psychologists have shown that most of us anticipate change as loss. Climate change is easy to interpret as loss: loss of prosperity, loss of freedom, loss of the good life as we have known it.

So What Can We Do?

Washington and Cook conclude by referring to the concept of 'implicatory denial'. Most of us are aware that scientists say climate change is under way, but even if we accept it as true we act as if it had no implications. We deny what it means, and continue business as usual. As I write these words, a large portion of Queensland is flooded, in what the global reinsurance company Munich Re estimates may be the most costly natural disaster in Australian history. An area larger than Germany and France combined has been inundated; over 200,000 people have been affected; 60,000 homes are without electricity; and three-quarters of the state has been declared a disaster area. Among other things, witnesses described an 'inland tsunami' - a wall of water 21 feet high and half a mile across - that swept over the Lockyer Valley. While the death toll is not yet known, at least 20 are known dead, many others missing.11

Some commentators were willing to describe the flooding as 'biblical', yet almost none were willing to make the connection to climate change.12 Of course, as scientists have repeatedly emphasized, 'climate' is by definition a matter of patterns, and one event does not a pattern make. But the Queensland floods are part of a pattern - a pattern that in 2010-2011 included devastating floods in China and Pakistan, unprecedented heatwaves and fires in Russia, and catastrophic mudslides in Brazil. Moreover, this pattern is consistent with what scientists have long predicted: that climate change would lead to an increase in extreme weather events. The reason is simple: conservation of energy. If you trap more energy in the atmosphere, it has to go somewhere, and one of the places it goes into is weather.

Australian Premier of Queensland Anna Bligh has said that the devastation in Queensland 'may be breaking our hearts, but it will not break our will'.13 Yet the will that is needed - which has been needed for the past two decades - is not the will to keep calm and carry on in the face of tragedy. It is the will to change the way we live in order to avoid an even greater tragedy; a tragedy that will affect not just Queensland, or even all Australia, but the whole world, including the plants and animals with whom we share this rock upon which we live. For, as Washington and Cook rightly note, climate change is about the way we live. It is about how we use energy without regard for the long-term consequences, and how we inflict environmental damage without concern for other people and species. It is about a way of life that does not reckon the true cost of living, an economics that does not take into account environmental damage and loss.

Climate change is the ultimate accounting: it is the bill for a century of unprecedented prosperity, generated by the energy stored in fossil fuels. By and large, this prosperity has been a good thing. More people live longer and healthier lives than before the industrial revolution. The problem, however, is that those people did not pay the full cost of that prosperity. And the remainder of the bill has now come due.

Anna Bligh is right. What we need now is will: the will to face the facts, the will to accept their implications and the will to do something about it. Let us hope this fine book helps us to move in that direction.

Naomi Oreskes

Professor of History and Science Studies

University of California (San Diego)

January 2011

Notes

1 Spencer Weart (2004) The Discovery of Global Warming, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; James Roger Fleming (1998) Historical Perspectives on Climate Change, Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

2 James Roget Fleming (2009) The Callendar Effect: The Life and Work of Guy Stewart Callendar (1898-1964), The Scientist Who Established the Carbon Dioxide Theory of Climate Change, The American Meteorological Society, Boston, MA; E. O. Hulburt (1931) 'The temperature of the lower atmosphere of the Earth', Physical Review, vol 38, 15 November, ppl876-1890.

3 Naomi Oreskes (2004) 'The scientific consensus on climate change', Science, vol 306, p1686; see also Peter T. Doran and Maggie Kendall Zimmerman (2009) 'Examining the scientific consensus on climate change', EOS, Transactions, American Geophysical Union, vol 90, no 3, p22, doi:10.1029/2009EO030002.

4 IPCC (2007) 'Summary for policymakers', in Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M. L. Parry, O. F. Canziani, J. P. Palutikof, P. J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson (eds), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp7-22.

5 Verner E. Suomi, in Jule Charney et al (1979) Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment, Report of an Ad-Hoc Study Group on Carbon Dioxide and Climate, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, 23-27 July, to the Climate Research Board, National Research Council, National Academies Press, Washington, DC, p2.

6 Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway (2010) Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, Bloomsbury Press, New York, NY.

7 Quote: 'you can double [carbon dioxide] and quadruple it and it has no effect ... To demonize it shows that you don't understand schoolchild science' (Ian Plimer, interviewed on ABN Newswire, June 2009, cited at www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=Ian_Plimer).

8 Prosenjit Ghosh and Willi A. Brand (2003) 'Stable isotope ratio mass spectrometry in global climate change research', International Journal of Mass Spectrometry, vol 228, no 1, pp1-33.

9 James Hansen (2010) Storms of My Grandchildren, Bloomsbury Press, New York, NY, p238.

10 On public opinion about climate change, see Anthony Leiserowitz et al (2010) Knowledge of Climate Change Across Global Warming's Six Americas, Yale Project on Climate Change Communication, http://environment.yale.edu/climate/files/Knowledge%20Across%20Six%20Americas.pdf.

11 See www.smh.com.au/business/insured-losses-from-deluge-could-reach-6bn-worldwide-20110114-19re8.html; www.ft.com/cms/s/0/caeec346-lffe-lleO-a6fb-00144feab49a.html#axzzlB3enDB27; www.ecoworld.com/waters/inland-tsunami-kills-10-in-queensland-australia.html.

Down