"We are here to make a choice between the quick and the dead." Bernard Baruch, 1946.

"We are here to make a choice between the quick and the dead." Bernard Baruch, 1946."We just barely scraped through the mid-term exam in the last century: we acquired the ability to destroy our civilization directly, by war, and we managed not to use it. Now it's the final exam, with the whole environment that our civilization depends on at stake. It's not just about knowledge and technical ability; it is also about self-restraint and the ability to cooperate. Grown-up values, if you like. How fortunate that we should be set such a test at a point in our history where we have at least some chance of passing it. And how interesting the long future that stretches out beyond it will be, if we do pass." Gwynne Dyer, last paragraph of Climate Wars, 2008.

I am inclined to scan & reproduce the last chapters of James Lovelock's The Revenge of Gaia and Gwynne Dyer's Climate Wars. Not that I think either of them is holy writ, just that it might be a fitting end to this thing here - and I have already posted the best T&A I have seen in recent memory :-)

maybe I will ... ok here they are:

The Revenge of Gaia, James Lovelock, 2006 - Chapter 9 - Beyond the Terminus, and,

Climate Wars, Gwynne Dyer, 2008 - Chapter Seven - Childhood's End.

Lovelock is just a bourgeois twit who keeps trying to convince us, "I'm a scientist" (really I am) and Dyer is a realist who knows how to speak respectfully of his loved-ones ... worth reading, critically that is - I think both of them indulge in kitchen-sink-ism as a coverup to not having (yet) thought the thing completely through, they should both read Charles Taylor's A Secular Age and Northrop Frye's Creation and Recreation (in that order) - maybe they will :-)

the OED tells us that head-work is: 1a. Mental work; brain-work; 1b. The practice of carrying loads on the head; 1c. Skill in games and sports; Hence head-worker, one who works with his head or brain; or, 2. An ornament for the keystone of an arch; or, 3. Apparatus for controlling the flow of water in a river or canal.

but I would say that headwork (without the dash) is fixing or repairing your head. Like the new-agers when they say 'bodywork'. I mentioned in the last post that I was going to see about revising my 'arguments for the existence of God' based on Northrop Frye's judegment that the clock-maker analogy was ... fatuous ... that would be headwork seems to me, or a post some time ago I am fixing my window ... a-and I think I have some that needs doing :-)

Be well (O best-beloved :-)

Annual Meeting of the Masters of the World

How about the slogan, "You're the Boss!"?

Excellent Gary. It will sell well among the poor.

But, "Changing the World Together," will fool a larger segment of the market.

this is neat, a little typographical trick ... not sure what it's good for but ... neat!

this is neat, a little typographical trick ... not sure what it's good for but ... neat!

"Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death." Macbeth, Act 5 Scene 5.

what I was actually thinking was, "another and another and another," and it felt like a literary quotation of some kind but Google turned up nothing and I thought of Shakespeare ... Macbeth is not particularly auspicious but ok.

so here's k-k-Canada: round numbers 700 giga tons of carbon annually, 35 million people ... 700,000,000 / 35,000,000 = 20, ok, 20 tons of carbon per person per year

which tallies with what I thought I knew from 'general knowledge' and overall guilt trips inc. (somewhere in my blogs I posted a chart showing Canada's relative position among the nations of the world ... and do you think I can find it? ai ai ai! ... ok, here it is Canada (?), but it was a "Climate Change Performance Index" which is a more complicated number than a Carbon Footprint, so, details here)

you would think, with all the noise, that there would be a quick-and-easy Carbon Footprint calculator ... and there are some for sure, most seem to be connected with a commercial enterprise trying to sell you Carbon Offsets of one kind and another, even BP has a relatively good one (relative to very poor that is)

you would think, with all the noise, that there would be a quick-and-easy Carbon Footprint calculator ... and there are some for sure, most seem to be connected with a commercial enterprise trying to sell you Carbon Offsets of one kind and another, even BP has a relatively good one (relative to very poor that is)eventually I stumbled on the CBC news article below and found Zerofootprint where they have a carbon calculator for Toronto ... do they have other cities? just a sec ... sort of ... you can browse around in there and see

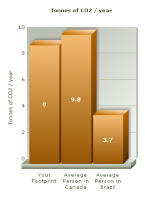

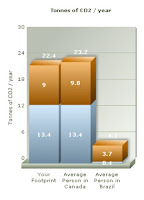

so I did mine, not a sophisticated calculation, and I wound up with the top bar graph at the right, but, waidaminit! 9.0! wtf? and the national average is 9.8? doh?!

anyway, pissed around for a few minutes and saw a little tick box, "With Goods and Services Footprint," aha!

and a little pop-up explanation, "Toggles the goods and services footprint on and off. Your ‘personal average’ is the environmental impact of your everyday decisions, as calculated in this calculator. Your ‘goods and services footprint’ is the remaining impact of you country’s economy which you are indirectly associated with - for example the impact of a mining company or a forestry company in your country. All values are per capita values for a given country calculated from the Living Planet Report 2006."

and a little pop-up explanation, "Toggles the goods and services footprint on and off. Your ‘personal average’ is the environmental impact of your everyday decisions, as calculated in this calculator. Your ‘goods and services footprint’ is the remaining impact of you country’s economy which you are indirectly associated with - for example the impact of a mining company or a forestry company in your country. All values are per capita values for a given country calculated from the Living Planet Report 2006."my antennae are already up on these Zerofootprint people, sounds like bureaucratic gobbledegook ... but ok, found a link to Living Planet Report 2006, by the WWF it turns out

and the antennae are still saying to me, "waidaminit, how come these guys didn't put the link right in there? why didn't they say 'WWF' up front? (is the WWF really the authority here?) ... ok ok, jury is still out, maybe you are just supposed to know ... but ... why do you have to turn ON the so called "Goods and Services" bar? (aptly named I must say :-)

Northrop Frye is eloquent on the subject of paranoia ... he has read Thomas Pynchon as he mentions in Double Vision and there is a good bit on paranoia in Creation & Recreation just go there and CTRL-F on 'paran' should pick it up ... paranoia is not all bad let's say ... well at least I don't subscribe to conspiracy theories :-)

worth looking at these numbers, I picked Brasil for my comparison country, not only is the personal average less than half, the Goods and Services is a tiny fraction too 1/33 - and that's counting the burning of the Amazon Rain Forest - but we already knew Canada is with the bad guys in this movie eh? black hats.

Comic relief:

Pam Veinotte, Parks Canada's field unit superintendent for Lake Louise, Yoho and Kootenay, said park wardens are probing a report about “an unusual discharge that temporarily flowed into Louise creek from Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise.”

Pam Veinotte, Parks Canada's field unit superintendent for Lake Louise, Yoho and Kootenay, said park wardens are probing a report about “an unusual discharge that temporarily flowed into Louise creek from Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise.”

“We certainly take these matters very seriously and we are working to uphold the highest level of environmental stewardship,” she said.

“We certainly take these matters very seriously and we are working to uphold the highest level of environmental stewardship,” she said.Yeah right ... 'the highest level of environmental stewardship' ... maybe she could toilet-train Stephen Harper & Jim Prentice?

Appendices:

1. Toronto website calculates personal carbon footprint, CBC, February 26 2008.

2. The Revenge of Gaia, James Lovelock, 2006.

3. Climate Wars, Gwynne Dyer, 2008.

4. The Baruch Plan, Bernard Baruch, June 14 1946.

***************************************************************************

Toronto website calculates personal carbon footprint, CBC, February 26 2008.

The City of Toronto is helping Torontonians get green with a new website that calculates their individual carbon footprint and offers tips on how to minimize their impact on the environment.

Toronto.zerofootprint.net features an online carbon footprint calculator that allows people to tally how many tonnes of carbon dioxide they produce as a result of their day-to-day activities.

Visitors to the site need about 30 minutes to answer questions about travel, where they buy their food and how they use energy in their homes. For instance, those who cycle or walk to work will get a better score compared to those who drive.

The average Torontonian's carbon footprint measures 8.6 tonnes per year, on a scale that reaches up to 20. That's lower than the average American's footprint, which measures at about 11.9 tonnes, but more than a citizen of the United Kingdom, pegged at around 5.3 tonnes.

By determining how much carbon dioxide they are contributing to the atmosphere, participants will hopefully be able to identify where they can curb their "emissions," which contribute to climate change and global warming.

Mayor David Miller and environmental groups said they are hoping entire neighbourhoods will use the new site to compare their footprints with others in the country and around the world.

Miller said he hopes the site will help Toronto reach its goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 6 per cent over the next 4 years and by 80 per cent by 2050.

The Zerofootprint Toronto project, launched during the C40 Large Cities conference in New York last year, is the first of its kind in Canada.

***************************************************************************

The Revenge of Gaia, James Lovelock, 2006.

[146]

Chapter 9 - Beyond the Terminus

Like the Norns in Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, we are at the end of our tether, and the rope, whose weave defines our fate, is about to break.

Gaia, the living Earth, is old and not as strong as she was two billion years ago. She struggles to keep the Earth cool enough for her myriad forms of life against the ineluctable increase of the sun's heat. But to add to her difficulties, one of those forms of life, humans, disputatious tribal animals with dreams of conquest even of other planets, has tried to rule the Earth for their own benefit alone. With breathtaking insolence they have taken the stores of carbon that Gaia buried to keep oxygen at its proper level and burnt them. In so doing they have usurped Gaia's authority and thwarted her obligation to keep the planet fit for life; they thought only of their own comfort and convenience.

Some time towards the end of the 1960s I walked along the quiet back lane of Bowerchalke village with my friend and near neighbour William Golding; we were talking about a recent visit I had made to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California and the idea of searching for life on other planets. I told him why I thought that both Mars and Venus were lifeless and that the Earth was more than just a planet with life, and why I saw it somehow in certain ways alive. He immediately said, 'If you intend to put forward so large an idea you must give it a proper name, and I suggest that you call it Gaia.' I was truly grateful to have his gift of this simple, powerful name for my ideas about the Earth. I gladly accepted it then as a scientist acknowledging an earlier literary reference, just as others in previous centuries referred to Gaia when naming the Earth sciences geology, geography and so [147] on. At that time I knew little of Gaia's biography as a Greek goddess and never imagined that the New Age, then just beginning, would take Gaia as a mythic goddess again. In a way, however harmful this has been to the acceptance of the theory in science, the New Agers were more prescient than the scientists. We now see that the great Earth system, Gaia, behaves like the other mythic goddesses, Khali and Nemesis; she acts as a mother who is nurturing but ruthlessly cruel towards transgressors, even when they are her progeny.

I know that to personalize the Earth System as Gaia, as I have often done and continue to do in this book, irritates the scientifically correct, but I am unrepentant because metaphors are more than ever needed for a widespread comprehension of the true nature of the Earth and an understanding of the lethal dangers that lie ahead.

After forty years living with the concept of Gaia I thought I knew her, but I realize now that I underestimated the severity of her discipline. I knew that our self-regulating Earth had evolved from those species that left a better environment for their progeny and by the elimination of those who fouled their habitat, but I never realized just how destructive we were, or that we had so grievously damaged the Earth that Gaia now threatens us with the ultimate punishment of extinction.

I am not a pessimist and have always imagined that good in the end would prevail. When our Astronomer Royal, Sir Martin Rees, now President of the Royal Society, published in 2,004 his book Our Final Century, he dared to think and write about the end of civilization and the human race. I enjoyed it as a good read, full of wisdom, but took it as no more than a speculation among friends and nothing to lose sleep over.

I was so wrong; it was prescient, for now the evidence coming in from the watchers around the world brings news of an imminent shift in our climate towards one that could easily be described as Hell: so hot, so deadly that only a handful of the teeming billions now alive will survive. We have made this appalling mess of the planet and mostly with rampant liberal good intentions. Even now, when the bell has started tolling to mark our ending, we still talk of sustainable development and renewable energy as if these feeble offerings would [148] be accepted by Gaia as an appropriate and affordable sacrifice. We are like a careless and thoughtless family member whose presence is destructive and who seems to think that an apology is enough. We are part of the Gaian family, and valued as such, but until we stop acting as if human welfare was all that mattered, and was the excuse for our bad behaviour, all talk of further development of any kind is unacceptable.

So often when disaster visits we still cry, 'How could God have let this happen?' And now that there is a probability that most of us will perish, can belief in God continue? Darwin once described the evolutionary process as 'clumsy, wasteful, blundering, low and horribly cruel'. But surely not as cruel, or as culpable, as we have been and still are to the rest of life on Earth; especially since so many other innocent species will share our fate.

It would be easy to think of ourselves and our families as incarcerated in a planet-sized condemned cell -- a cosmic death row -- awaiting inevitable execution. The days and years will pass, the seasons continue and we will be fed and entertained, and if we have faith we will ask God for a reprieve. Some like Sandy and me will probably cheat the executioner and die before our time is due; the cruel consequences will come for our children and grandchildren.

I am a scientist and think in terms of probabilities not certainties and so I am an agnostic. But there is a deep need in all of us for trust in something larger than ourselves, and I put my trust in Gaia, and declared it in my autobiography, Homage to Gaia, in 2,000. Was ever a trust so severely tested?

As is often the way with lesser crises I turn to my friend and mentor, Sir Crispin Tickell, and it happened that he had an answer in the form of an address he gave before a conference on The Earth Our Destiny, at Portsmouth Cathedral in 2002,. It was a deeply moving, wise and helpful observation on our place in the environment. The last paragraphs of the text were:

The ideology of industrial society, driven by notions about economic growth, ever-rising standards of living, and faith in the technological fix, is in the long run unworkable. In changing our ideas, we have to look forward [149] towards the eventual target of a human society in which population, use of resources, disposal of waste, and environment are generally in healthy balance.He concluded with the words of the twelfth-century abbess Hildegard of Bingen, who wrote of God:

Above all we have to look at life with respect and wonder. We need an ethical system in which the natural world has value not just for human welfare but for and in itself. The universe is something internal as well as external.

... I ignite the beauty of the plains,In certain ways the human world is re-enacting the tragedy of Napoleon's advance on Moscow in 1812.. In September of that year, when he reached the Russian capital, he had already gone too far, and his precious supplies were daily being consumed while he consolidated his capture. He was unaware that the irresistible forces commanded by General Winter were siding with the Russians, allowing them to counterattack and regain their losses. The only way he could have avoided defeat was an immediate and professionally executed retreat so that his army could remain intact to fight another time. The quality of generalship is measured in military circles by the ability to carry through and organize a successful retreat.

I sparkle the waters,

I burn in the sun, and the moon and the stars . . .

I adorn all of the Earth,

I am the breeze that nurtures all things green . . .

I am the rain coming from the dew that causes the grasses to laugh with the joy of life.

Let us likewise rejoice.

The British remember with pride the successful withdrawal of their army from Dunkirk in 1940, and do not see it as an ignominious defeat. It was certainly not a victory, but it was a successful and sustainable retreat. The time has come when all of us must plan a retreat from the unsustainable place that we have now reached through the inappropriate use of technology; far better to withdraw now while [150] we still have the energy and the time. Like Napoleon in Moscow we have too many mouths to feed and resources that diminish daily while we make up our minds. The retreat from Dunkirk was not just good generalship: it was aided by an amazing expression of spontaneous unselfish good will from those numerous civilians who willingly risked their lives and their small boats to cross the channel to rescue their army. We need the people of the world to sense the real and present danger so that they will spontaneously mobilize and unstintingly bring about an orderly and sustainable withdrawal to a world where we try to live in harmony with Gaia.

Economists and politicians have to square the utter necessity of a rapid and controlled shutdown of emissions from fossil fuel burning with the human needs of civilization. Economic growth is as addictive to the body politic as is heroin to one of us; perhaps we have to keep the craving in check by using a safer substitute, an economist's methadone. I would suggest again that the mobile phone, the internet and entertainment from computers are moves in the right direction; they use time and energy that might otherwise be spent travelling by car or aircraft. Moreover, there is information technology and the efficient use of energy, for example using the ultra efficient white light emitting diodes (WLEDs) to see at night. Should technology of this kind become the main source of economic growth it would let us spend our lives harmlessly and fill some of the time that now we use in fuel-consuming travel. To an extent we are evolving that way.

Until quite recently, although many of us were aware that serious environmental change could happen and believed the predictions of the IPCC, somehow our knowledge seemed theoretical and academic, not indicating that something deadly was imminent. It was a small event that awakened me to these dangers. Fear crystallized as sharp needles in the supersaturated spaces of my mind when, in October 2003, my near neighbours, Christine and Peter Hadden, told me of plans to erect giant wind turbines in the countryside near our homes. Suddenly I realized what our politicians meant by sustainable development and renewable energy, and what it would do to the last remaining good countryside of West Devon. I could almost hear them say, 'Let us harvest the wind for energy, and plant bio fuel crops to keep the [151] cars of urban voters running. We can do it without polluting the air or tangling with that nasty, dirty, fearful nuclear stuff.'

By good countryside I mean farming land and communities that live well with the Earth and represent an ecosystem which, although dominated by people, has ample room left for woodlands, hedgerows and meadows. Most of southern England was like this before 1940, and the largest remaining parts are in the West Country, especially in Devon. In my mind these last remaining areas of countryside were the face of Gaia, and it was about to be sacrificed. It was this that awakened my fury, and made me fully aware of the coming crisis of global heating. To make good countryside into industrial parks for wind energy merely as a gesture to prove their environmental credentials showed how far our leaders were from understanding our peril. To keep their urban enclaves comfortable, they would devastate by industrial development the remaining areas of good countryside.

I moved to West Devon twenty-eight years ago to escape the bulldozers that were destroying the Wiltshire hedgerows and meadows. Unwisely I thought that the gentle farmland of Devon was too poor to be developed and would let me live out my life in a countryside I loved. I had not allowed for incessant ideological good intentions and the near-religious belief in renewable energy and sustainable development for the good of us all.

They call Sandy and me 'NIMBYs' because we fight their final solution to the energy problem. Perhaps we are NIMBYs, but we see those urban politicians as like some unthinking physicians who have forgotten their Hippocratic Oath and are trying to keep alive a dying civilization by useless and inappropriate chemotherapy when there is no hope of cure and the treatment renders the last stages of life unbearable.

So is our civilization doomed, and will this century mark its end with a massive decline in population, leaving an impoverished few survivors in a torrid society ruled by warlords on a hostile and disabled planet? I hope that it will not be that bad; once a technically advanced nation wakes up to its responsibility, perhaps in response to our alarm call, they will say 'we can fix it.' They might use something like [152] space-mounted sunshades or Latham's floating nuclei generators that put white reflecting clouds across the ocean surface. Technological fix it may be, but if it works we have only ourselves to blame if we do not take advantage.

Sunshades for cooling the Earth are more valuable than they might at first appear; they could wholly neutralize the harmful effects of unscheduled methane releases. They might even provide an adjustable remedy ready to offset the global heating should the methane clathrates of the ocean suddenly escape into the atmosphere. Keeping in mind the similarity of the Earth's physiology to that of a human, it is useful to compare such a technological fix with the use by paramedics of oxygen for heart failure and breathing difficulty, or a pressure pad for haemorrhage -- something temporary, to keep a patient alive until they reach the full services of a hospital.

By itself this fix will do no more than buy us time to change our damaging way of life, because if we continue to burn fossil fuels and let the carbon dioxide rise in abundance, ocean life, essential to the health of Gaia, will be further damaged. But we may risk it because time is needed to instal equipment for carbon sequestration and for nuclear fusion and whatever forms of economically sensible renewable energy become available. In the longer term we have to understand that however benign a technological solution may seem it has the potential to set humanity on a path to the ultimate form of slavery. The more we meddle with the Earth's composition and try to fix its climate, the more we take on the responsibility for keeping the Earth a fit place for life, until eventually our whole lives may be spent in drudgery doing the tasks that previously Gaia had freely done for over three billion years. This would be the worst of fates for us and reduce us to a truly miserable state, where we were forever wondering whether anyone, any nation or any international body could be trusted to regulate the climate and the atmospheric composition. The idea that humans are yet intelligent enough to serve as stewards of the Earth is among the most hubristic ever.

So what should a sensible European government be doing now? I think we have little option but to prepare for the worst and assume that we have already passed the threshold. Like paramedics, their first [153] priority is to keep the patient, civilization, alive during the journey to a world that at least is no longer undergoing rapid change. We face unrestrained heat, and its consequences will be with us within no more than a few decades. We should now be preparing for a rise of sea level, spells of near-intolerable heat like that in Central Europe in 2003, and storms of unprecedented severity. We should also be prepared for surprises, deadly local or regional events that are wholly unpredictable. The immediate need is secure and safe sources of energy to keep the lights of civilization burning and for the preparation of our defences against the rising sea level. There is no alternative but nuclear fission energy until fusion energy and sensible forms of renewable energy arrive as a truly longterm provider. Nuclear energy is free of emissions and independent of imports from what will be a disturbed world. We would be right to cut back all emissions to a minimum, and this includes emissions of methane from leaking pipes and landfill sites. But most of all we need electricity to sustain our technologically based civilization.

In several ways we are unintentionally at war with Gaia, and to survive with our civilization intact we urgently need to make a just peace with Gaia while we are strong enough to negotiate and not a defeated, broken rabble on the way to extinction. Can the present-day democracies, with their noisy media and special-interest lobbies, act fast enough for an effective defence against Gaia? We may need restrictions, rationing and the call to service that were familiar in wartime and in addition suffer for a while a loss of freedom. We will need a small permanent group of strategists who, as in wartime, will try to out-think our Earthly enemy and be ready for the surprises bound to come. Globally, the climate agencies of the UN have performed magnificently, as the IPCC proves. But as the climate worsens individual nations will need more and more to address disasters locally as they happen. In a sense, the great party of the twentieth century, with its extravagant overspending and its war games, is over. Now is the time for washing up and throwing out the debris.

My wisest of friends, Jane and Peter Horton, have warned me that the metaphor of war and battles with Gaia is masculine and could be offensive to women who now at last have power and influence on the [154] way we act. They prefer my metaphor of Gaia as the stern but nurturing mother. They may well be right, but I ask them, as I ask Earth scientists who so dislike my image of a living Earth, to consider metaphor seriously as a path to the primitive feelings of the unconscious part of our minds. We are two sexes who respond differently and both metaphors may be needed. We belong to the family of Gaia and are like a revolting teenager, intelligent and with great potential, but far too greedy and selfish for our own good.

Men and women both need to be aware of what we are missing. Already for most of us the artificial world of the city is the whole of our lives and we think that to survive all we need is to be streetwise. But even in the city a few remnants of the natural world still continue in the parks and gardens. Make the most of them, for they continue to die away, as does the countryside many know and love; they are precious indeed.

If it should be that we have already passed the threshold of irreversible heating, then perhaps we should listen to the deep ecologists and let them be our guide. One of them that I know well as a friend is the biologist Stephan Harding, and I am indebted to him for making me aware of deep ecology. This small band of deep ecologists seem to realize more than other green thinkers the magnitude of the change of mind needed to bring us back to peace within Gaia, the living Earth. Like the holy men and women who make their whole lives a testament to their faith, the deep ecologists try to live as a Gaian example for us all to follow.

Few of us now can change our lives sufficiently to express our allegiance to Gaia as they do, but I suspect the changes soon to come will force the pace, and just as civilization ultimately benefited in the earlier dark ages from the example of those with faith in God, so we might benefit from those brave deep ecologists with trust in Gaia. The monasteries carried through that earlier Dark Age the hard-won knowledge of the Greek and Roman civilizations, and perhaps these present-day guardians could do the same for us. Despite all our efforts to retreat sustainably, we may be unable to prevent a global decline into a chaotic world ruled by brutal war lords on a devastated Earth. If this happens we should think of those small groups of monks [155] in mountain fastnesses like Montserrat or on islands like lona and Lindisfarne who served this vital purpose.

Few travellers from the north would go to the tropical south without antimalarial drugs, or to the Middle East without checking how the local war was progressing. By comparison our journey into the future is amazingly unprepared. Where people know well the local danger, as in Tokyo, they prepare for the earthquake to come. When the threats are global in scale we ignore them. Volcanoes, like Tamboura, Indonesia, in 1814 and Laki, Iceland, in 1783, were much more powerful than was Pinatubo in the Philippines (1991), or Krakatoa in Indonesia (1887). They affected the climate enough to cause famine, even when our numbers were only a tenth of what they are now. Should one of these volcanoes stage a repeat performance, do we have now enough stored food for tomorrow's multitudes? If part of the Greenland or Southern glaciers slid into the sea, the level of the sea might rise by a metre all over the world. This event would render homeless millions of those living in coastal cities. Citizens would suddenly become refugees. Do we have the food and shelter needed when cities such as London, Calcutta, Miami and Rotterdam become uninhabitable?

We are sensible and we do not agonize over these possible doom scenarios. We prefer to assume that they will not happen in our lifetimes. We take them no more seriously than our forefathers took the prospect of Hell, but the thought of appearing foolish still scares us. An old verse goes, 'They thieve and plot and toil and plod and go to church on Sunday. It's true enough that some fear God but they all fear Mrs Grundy.' In science we have our Drs Grundy also, and they are all too eager to scorn any departure from the perceived dogma. Scientists and science advisers are afraid to admit that sometimes they do not know what will happen. They are cautious about their predictions and do not care to speak in a way that might threaten business as usual. This tendency leaves us unprepared for a catastrophe such as a global event that is wholly unexpected and unpredicted -- something like the creation of the ozone hole but much more serious; something that could throw us into a new dark age.

We can neither prepare against all possibilities, nor easily change [156] our ways enough to stop breeding and polluting. Those who believe in the precautionary principle would have us give up, or greatly decrease, burning fossil fuel. They warn that the carbon dioxide byproduct of this energy source may sooner or later change, or even destabilize, the climate. Most of us know in our hearts that these warnings should be heeded but know not what to do about it. Few of us will reduce their personal use of fossil fuel energy to warm, or cool, their homes or drive their cars. We suspect that we should not wait to act until there is visible evidence of malign climate change -- for by then it might be too late to reverse the changes we have set in motion. We are like the smoker who enjoys a cigarette and imagines giving up smoking when the harm becomes tangible. Most of all we hope for a good life in the immediate future and would rather put aside unpleasant thoughts of doom to come.

We cannot regard the future of the civilized world in the same way as we see our personal futures. It is careless to be cavalier about our own death. It is reckless to think of civilization's end in the same way. Even if a tolerable future is probable it is still unwise to ignore the possibility of disaster.

One thing we can do to lessen the consequences of catastrophe is to write a guidebook for our survivors to help them rebuild civilization without repeating too many of our mistakes. I have long thought that a proper gift for our children and grandchildren is an accurate record of all we know about the present and past environment. Sandy and I enjoy walking on Dartmoor, much of which is featureless moorland. On such a landscape it is easy to get lost when it grows dark and the mists come down. We usually avoid this mishap by making sure that we always know where we are and what path we took. In some ways our journey into the future is like this. We can't see the way ahead or the pitfalls but it would help to know what the state is now and how we got here. It would help to have a guidebook written in clear and simple words that any intelligent person can understand.

No such book exists. For most of us, what we know of the Earth comes from books and television programmes that present either the single-minded view of a specialist or persuasion from a talented lobbyist. We live in adversarial, not thoughtful, times and tend to hear [157] only the arguments of each of the special-interest groups. Even when they know that they are wrong they never admit it. They all fight for the interests of their group while claiming to speak for humankind. This is fine entertainment, but what use would their words be to the survivors of a future flood or famine? When they read them in a book drawn from the debris would they learn what went wrong and why? What help would they gain from the tract of a green lobbyist, the press release of a multinational power company, or the report of a governmental committee? To make things worse for our survivors, the objective view of science is nearly incomprehensible. Scientific papers and books are so arcane that scientists can only understand those of their own speciality. I doubt if there is anyone, apart from these specialists, who can understand more than a few of the papers published in Science or Nature every week.

Scan the shelves of a bookshop or a public library for a book that clearly explains the present condition and how it happened. You will not find it. The books that are there are about the evanescent things of today. Well-written, entertaining, or informative they may be, but almost all of them are in the current context. They take so much for granted and forget how hard won was the scientific knowledge that gave us the comfortable and safe life we enjoy. We are so ignorant of those individual acts of genius that established civilization that we now give equal place on our bookshelves to the extravagance of astrology, creationism and homeopathy. Books on these subjects at first entertained us or titillated our hypochondria. We now take them seriously and treat them as if they were reporting facts.

Imagine the survivors of a failed civilization. Imagine them trying to cope with a cholera epidemic using knowledge gathered from a tattered book on alternative medicine. Yet in the debris such a book would be more likely to have survived and be readable than a medical text.

What we need is a book of knowledge written so well as to constitute literature in its own right. Something for anyone interested in the state of the Earth and of us -- a manual for living well and for survival. The quality of its writing must be such that it would serve for pleasure, for devotional reading, as a source of facts and even as a primary school text. It would range from simple things such as how to light a fire, to [158] our place in the solar system and the universe. It would be a primer of philosophy and science -- it would provide a top-down look at the Earth and us. It would explain the natural selection of all living things, and give the key facts of medicine, including the circulation of the blood, the role of the organs. The discovery that bacteria and viruses caused infectious diseases is relatively recent; imagine the consequences if such knowledge was lost. In its time the Bible set the constraints for behaviour and for health. We need a new book like the Bible that would serve in the same way but acknowledge science. It would explain properties like temperature, the meaning of their scales of measurement and how to measure them. It would list the periodic table of the elements. It would give an account of the air, the rocks, and the oceans. It would give schoolchildren of today a proper understanding of our civilization and of the planet it occupies. It would inform them at an age when their minds were most receptive and give them facts they would remember for a lifetime. It would also be the survival manual for our successors. A book that was readily available should disaster happen. It would help bring science back as part of our culture and be an inheritance. Whatever else may be wrong with science, it still provides the best explanation we have of the material world.

It is no use even thinking of presenting such a book using magnetic or optical media, or indeed any kind of medium that needs a computer and electricity to read it. Words stored in such a form are as fleeting as the chatter of the internet and would never survive a catastrophe. Not only is the storage media itself short-lived but its reading depends upon specific hardware and software. In this technology, rapid obsolescence is usual. Modern media is less reliable for longterm storage than is the spoken word. It needs the support of a high technology that we cannot take for granted. What we need is a book written on durable paper with long-lasting print. It must be clear, unbiased, accurate and up to date. Most of all, we need to accept and to believe in it at least as much as we did, and perhaps still do, the World Service of the BBC.

In the dark ages of our earlier history the religious orders in their monasteries carried through the essence of what makes us civilized. [159] Much of this knowledge was in books, and the monks took care of them and read them as part of their discipline. Sadly, we no longer have callings like this. The vast collection of knowledge that is now available is more than any one person could hold. Consequently it is divided and subdivided into subjects. Each subject is the province of professionally employed specialists. Most are expert in their own subject but ignorant of the others -- few have a sense of vocation.

Apart from isolated institutes like the National Centre for Atmospheric Research perched on a mountain side in Colorado, there are no equivalents of the monasteries. So who would guard the book? A book of knowledge written with authority and as splendid a read as Tyndale's Bible might need no guardians. It would earn the respect needed to place it in every home, school, library and place of worship. It would then be to hand whatever happened.

Meanwhile in the hot arid world survivors gather for the journey to the new Arctic centres of civilization; I see them in the desert as the dawn breaks and the sun throws its piercing gaze across the horizon at the camp. The cool fresh night air lingers for a while and then, like smoke, dissipates as the heat takes charge. Their camel wakes, blinks and slowly rises on her haunches. The few remaining members of the tribe mount. She belches, and sets off on the long unbearably hot journey to the next oasis.

***************************************************************************

Gwynne Dyer, Climate Wars - Chapter Seven: Childhood's End.

[233]

Chapter Seven - Childhood's End

The larger the proportion of the Earth's biomass occupied by mankind and the animals and crops required to nourish us, the more involved we become in the transfer of solar and other energy throughout the entire system. As the transfer of power to our species proceeds, our responsibility for maintaining planetary homeostasis increases, whether we are conscious of the fact or not. Each time we significantly alter part of some natural process of regulation or introduce some new source of energy or information, we are increasing the probability that one of these changes will weaken the stability of the entire system . . . We shall have to tread carefully to avoid the cybernetic disasters of runaway positive feedback or of sustained oscillation . . .THIRTY YEARS AGO, when independent scientist James Lovelock wrote his seminal first book about what is now called "Earth System Science" in academic circles, but which he boldly named "Gaia," his concluding remarks about the fate of the "planetary maintenance engineer" struck me so forcibly that I have been able to quote them verbatim ever since. The world in which our species built its civilization used to seem such a stable, welcoming place, and maintained its stability so effortlessly and even invisibly, that nobody in the past would have dreamed of wishing to take up that thankless role, even if they could have imagined that human beings might one day acquire the knowledge and the power to take over the management of the Earth system. But we are now well on the way to acquiring those abilities, at least in a rudimentary form, and it begins to look probable that we will need some of them.

This could happen if... man had encroached upon Gaia's functional powers to such an extent that he disabled her. He would then wake up one day to find that he had the permanent lifelong job of planetary maintenance engineer. Gaia would have retreated into the muds, and the ceaseless intricate task of keeping all the global cycles in balance would be ours. Then at last we should be riding that strange contraption, 'the spaceship Earth,' and whatever tamed and domesticated biosphere remained would indeed be our 'life support system' . . . Assuming the present per capita use of energy, we can guess that at less than 10,000 million [people] we should still be in a [234] Gaian world. But somewhere beyond this figure, especially if the consumption of energy increases, lies the final choice of permanent enslavement on the prison hulk of the spaceship Earth, or gigadeath to enable the survivors to restore a Gaian world.

— James Lovelock, Gala: A New Look at Life on Earth, 1979

Birth rates have dropped sharply in the three decades since Lovelock wrote his first book. As a result, we are still well short of the ten billion people he set as the point at which our numbers might simply overwhelm the natural systems that regulate the global temperature, the chemical composition of the atmosphere, and other key elements in the equation and thereby succeed (most of the time) in keeping conditions on the planet suitable for abundant life. We may never hit ten billion, and the further short of that destination that we fall, the better it will be. But our energy consumption per capita has increased vastly beyond what anybody in the 19705 could have imagined — [235] nobody then foresaw the rapidly industrializing Asia of today — and the net effect is about the same. We are overwhelming the natural systems, and rapidly approaching the "runaway positive feedbacks" that concerned Lovelock even so long ago.

In 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated that global emissions of greenhouse gases must peak by 2015 if we are to have any chance of keeping the temperature rise to two degrees Celsius (and thus have a reasonable chance of not tripping the feedback mechanisms that could pitch us into runaway heating). In the same year, the International Energy Agency predicted that world energy use will grow 50 percent by 2030, and that fossil fuels will account for 77 percent of that increase. Only instant massive mobilization and wartime-style controls in every major industrialized and industrializing country could stop the rise in greenhouse-gas emissions by 2015, and you know that is not going to happen. So we are going to bust the boundaries. Indeed, the question that looms over us is the same one that comes from the back seat of the family car every ten minutes on long drives: "Are we there yet?" "There" being, in this case, the point at which we have to accept the job of planetary maintenance engineer, at least temporarily—and I think the answer is "Yes."

It was probably already too late to avoid inheriting the job even thirty years ago, although that was not clear at the time because we did not comprehend the sheer momentum of the industrial systems that we have built. It is almost certainly too late now. And maybe it is not altogether a bad thing that the most sentient form of life on the planet is beginning to acquire some ability to regulate the working of Gaia, in our own interests first of all, but potentially in the interests of the entire system.

This statement will stoke instant rage in those to whom rage comes easily, and cause dismay in many more who are appalled by what human civilization has done to the planet in less than ten thousand years. How dare anybody propose human beings as the stewards of the biosphere when their whole history [236] shows that they are just a blight on the planet, devastating the land and emptying the sea of life? What the human race must do is leave everything that remains of the natural world alone to heal as best it can, and tread as lightly as we can upon the Earth. You can't trust us to intervene. Look at our track record.

Again, it's too late. That would have still been a viable course in 1800, but it isn't now. There are six and a half billion of us, and it is almost impossible to imagine a way that we can stop the growth before there are eight and a half billion. Our per capita energy use is immense, and it will continue to grow for at least two generations. The only way that our numbers could come down to a more "sustainable" total in less than several centuries is mass death through famine, war and disease. That may well happen, but I do not want it to: a great deal would be lost, and not just lives. Indeed, if the "wipeout" scenario has any relevance to our situation at all, then you definitely do not want high-technology human civilization to break down, because it provides us with the only set of tools that might enable us to avoid the very worst outcome of our current activities: a full-blown mass extinction.

Yes, of course: technically speaking, we have already initiated an extinction event simply by taking over so much of the planet's surface for our own purposes. The rate at which species are now disappearing is probably at least ten times higher than "normal," and maybe a hundred times higher. (More precise statements of the extinction rate are to be viewed with some suspicion, since nobody knows how many species there are.) But at the risk of sounding unsympathetic, I must point out that species come and go, and that 99 percent of those that ever lived were already extinct before human beings even evolved. For aesthetic reasons, we should stop decimating what is left of the large animal species that remain on the land and in the sea, but our most important priority is to preserve the species that perform vital functions in maintaining the biosphere (most of which are tiny and not in the least cuddly). That is a tricky business, in [237] part because we don't always know which ones they are, but it is much more important than saving polar bears.

To the extent that the biosphere has operated without human intervention to maintain the recent climatic equilibrium — that is, the ten-thousand-year spell of warm and stable climate during which we have built our civilization — we should of course leave it alone to get on with the job. But we should be honest with ourselves: we are actually seeking to preserve one particular climatic state among many potential ones, ranging from deep glaciation to greenhouse extinction, because it suits our particular needs and tastes. We should also be realistic about what needs to be done. We have destabilized this highly desirable climatic equilibrium by our own inadvertent interventions in the past (two hundred years of burning fossil fuels), but given where we are now, it is highly unlikely that we can achieve the goal of restoring that equilibrium without further large and deliberate interventions in the system. We don't know enough yet about how the system works to do that safely, but that doesn't mean that we must never do it. It means that we must learn a lot more about the climate system, very fast, so that we can do it more safely.

By failing to see that the Earth regulates its climate and composition, we have blundered into trying to do it ourselves, acting as if we were in charge. By doing this, we condemn ourselves to the worst form of slavery. If we choose to be the stewards of the Earth, then we are responsible for keeping the atmosphere, the ocean and the land surface right for life. A task we would soon find impossible ...[238]

To understand how impossible it is, think about how you would regulate your own temperature or the composition of your blood. Those with failing kidneys know the never-ending daily difficulty of adjusting water, salt and protein intake. The technological fix of dialysis helps, but is no replacement for living, healthy kidneys.

— James Lovelock, The Independent, January 16, 2006

I see Jim Lovelock as the most important figure in both the life sciences and the climate sciences for the past half-century. I suspect that in another hundred years, if enough from the present survives, he will be granted equal billing with Charles Darwin in the pantheon of scientific heroes. And here, in this quote from The Independent, he is saying that we must not do what I am recommending. To which I reply: if I have kidney disease, I definitely want dialysis. It might keep me alive long enough for a more permanent cure to be discovered, and at the least, it will give me more years with those I love.

Getting through the rest of this century without falling into the runaway global warming that Lovelock predicts is only likely if we do not breach the plus-2-degrees-Celsius boundary, and most climate scientists I have spoken to would feel a great deal easier if we never exceeded plus 1.5 degrees. Getting the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere back down to a relatively safe level — say, the 350 parts per million that James Hansen now advocates as a provisional target — would take even longer, for we passed that milestone some time in the 1980s. We can fully decarbonize our economies if we have enough time, but we are not going to achieve it on the schedule that is required if we are not to breach the boundary. We will pass 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide before 2012, we will probably hit 450 parts per million in the late 2020s, and it will be a miracle if we don't reach 500 parts per million before we can turn the tide.

We (and the biosphere in its current configuration) will only come through this crisis without huge losses if we can keep the temperature from going too high, despite what is happening in the short term to the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere. We are going to get the miserable job of planetary maintenance engineer for a while, but the goal must be to work ourselves out of a job: to restore the natural systems that have done an excellent job of keeping the planet suitable for abundant life most of the time for the past several billion years. This [239] is an emergency, however, and we have to intervene or all of Lovelock's predictions will come true.

What is being proposed is not intervention on a broad front. Nobody is suggesting that we take over the task of providing directly the ecosystem services that are now provided for free by ocean plankton, for example; rather, we should keep the sea surface temperature low enough for them to flourish. We don't know enough about the Earth system to do any fine tuning — but we probably do know how to keep the temperature below two degrees Celsius for the fifty or seventy-five years when we overrun the 450-parts-per-million boundary. If we don't, then we really are screwed.

But just keeping the temperature down artificially will not stop the oceans from becoming more and more acidic due to increased carbon dioxide, I hear a protester cry. No, it won't, but do you have some credible alternative that will stop acidification? Don't tell me "early and steep cuts in emissions," because I don't believe in the Climate Fairy. But we don't have to settle this debate right now. Let's wait five or ten years, and if those "early and steep cuts in emissions" still haven't happened, then we'll discuss it again. There's enough time for that.

In the meantime, though, I'd like lots of research to be done on geo-engineering techniques of all kinds, because I suspect that we will need them. A high level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has undesirable consequences that just keeping the temperature down cannot stop, but it would help a lot if we could keep the average global temperature low enough to avoid triggering large natural feedbacks that take the situation completely beyond our control. Keeping the temperature down could also prevent the kind of human catastrophes, including great wars, that would doom all our efforts to clear up the mess we have made.

The job, for the rest of this century, is repairing the damage we did over the past two centuries of industrialization to [240] the homeostatic, Gaian systems that we didn't even realize we depended upon until relatively recently. That does not mean that we de-industrialize — this global society will live or die as a high-energy enterprise — but to begin with we must completely de-carbonize our energy, our transportation, and our industry. Then much of the forests that we cut down over the past two hundred years must be replanted, huge no-fishing reserves must be created to permit the repopulation of the oceans, and the amount of land we have removed from the natural cycles in order to grow food on it must fall from the current 40 percent of the Earth's land surface to 30 percent or less. It's not too late to fix most of the damage, if we have enough time and are not fatally distracted by catastrophes.

And how do we feed the eight-and-a-half billion people of the mid-century world — or nine billion, or nine-and-a half, take your pick — while we are reducing the amount of land under cultivation and cutting back on fishing? This is a high-tech civilization, and I suspect that the answer lies in that direction. Alberta, for example, produces more wheat and beef than any other Canadian province, but it is approaching the limit in terms of available water. So it is looking into non-traditional ways of producing those commodities.

We really should be getting beyond growing the whole plant or the whole cow, when only certain parts are of primary value to us. If you think about wheat, it is primarily the kernel of wheat that is of primary importance to us ... There are significant advances in molecular biology and in cell biology. In the medical field, we're really quite far advanced in growing artificial skin. You start with a small patch of human skin, and you grow a large patch. There's no real reason to think that that cannot be extended to other parts of the human body . . . and if that is so, it isn't all that farfetched to think, well, why don't we just find ways of [241] growing steak, or fish fillets, from a few cells by providing the appropriate nutrient medium?Many people will simply be horrified by this proposal, and many others will suspect that the innocent little phrase, "possibly for different markets," foreshadows a two-tier world food system: real beef for the rich, vat-grown beef for the poor. Even if their taste and texture were exactly the same, considerations of prestige would produce that two-tier market. Still, it's a lot better than Soylent Green, and it could offer a way to uncouple human food production from the traditional farming techniques that have led us to alienate 40 percent of the world's surface — and the most productive 40 percent, at that — from its [242] proper task of contributing to the maintenance of the biosphere. We are going to see more proposals like this, and we are not going to be able to dismiss them out of hand.

What triggered this exploration in part was our discussion about water. In order to grow one kilogramme of beef, you require about thirteen thousand litres, thirteen thousand kilogrammes of water. The same is true for plants. Conceivably you can grow just the kernel, or just the starch that makes up the kernel, artificially . . . To grow a kilogramme of wheat flour takes about a thousand litres of water. If you want to visualize this as a milk carton of one litre, it takes about three bathtubs of water to produce that one milk carton of wheat flour. That's a very profligate way of using water, and with impending climate change, concerns about droughts, it's reasonable to try to explore other ways, not necessarily as replacements but as complements. And I think modern science is putting it within reach now . . .

It is not unnatural for a modern variant of an industry to have its roots in a traditional variant, so I could certainly foresee in the years to come that there will be farmers who could produce wheat or beef in both ways simultaneously, possibly for different markets.

— Axel Meisen, chair of foresight, Alberta Research Council, in an interview with the author, May 2, 2008

Let us make the heroic assumption, just for a moment, that the human race will be clever enough to make it through this century without triggering runaway warming and a massive population dieback. Let us further assume that we have retained our high-technology civilization (for otherwise our chances of making it through unscathed would be very small), and that the experience has taught us something about the need to respect the natural systems that we depend upon. You may see these as low-probability assumptions, but you cannot deny that they are at least possible. What would that somewhat chastened end-of-the-century global society look like?

It would be a world with much greater equality of wealth between the old rich countries and the Majority World, because that is a precondition for making it through the crisis. Even with the most stringent population controls there would probably still be five or six billion of us, although there might be a gradual downward trend. Since most of those five or six billion would have access to the full industrialized lifestyle, enormous emphasis would have to be put on learning to "live lightly on the planet." Given the right technologies, it is not improbable that most people would still have personal transportation devices of some sort, that long-distance travel would continue to be possible for more than the privileged few, that those who wished to would still be eating meat (although, in many cases, ethically produced, vat-grown meat). This is not a wish-fulfilment dream; it is what we would probably get if we pass the test.

Various metaphors for our present situation come to mind, but the one that really sticks is the final exam. For more than ten thousand years, human beings have built a civilization that is now global in extent, but for most of that time we were really semi-barbaric children. Only two centuries ago, slavery [243] was almost universal, women were an inferior caste almost everywhere, and war was the normal way of doing business. Resources were always scarce, so competition was usually a better strategy than cooperation. And, until the very end of that period, we had no real comprehension of the workings of the planet we lived on.

Then we began burning fossil fuels, and resources became abundant. Population and consumption both soared, of course, but so did science and knowledge. We began to understand our place in the universe, and that was very frightening. The nursery world that we thought we lived in, half playground, half battlefield, but unchanging and specially designed for human beings, turned out to be a fantasy. The real world was immensely old, it cared nothing for us, and there were many ways it could hurt us that we had never even imagined: ten-thousand-year volcanic cataclysms and hundred-metre sea level changes, ice ages and asteroid strikes, runaway greenhouse warming and supernovas a hundred light years away that could sterilise the planet. We realized we were on our own, and it was time to grow up.

We haven't done all that badly, really. We began by trying to behave better towards one another in our own societies — the great democratic revolutions, free universal education, the invention of the welfare state — and by the end of this two-century period we had even created semi-functional international institutions. Nobody would have put it this way at the time, but with hindsight you can see that we were actually building our capacity to take responsibility for people and events beyond our own horizons. Just as well, given what lies in wait for us. But it is worth remembering that all this only became possible because large numbers of people finally had the security and the leisure to think beyond the moment and to act for the future. We owe a lot to fossil fuels.

There was no alternative to burning fossil fuels in terms of getting an industrial, scientific civilization off the ground, because no other source of energy was available to a low-technology [244] society. (And it was a one-time-only offer: we have used up all the easily accessible sources of fossil fuel, and any descendants of ours who are trying to restart an industrial civilization will be out of luck.) We went on burning coal and oil and gas heedlessly for almost two centuries, not suspecting that, in the long run, dependence on fossil fuels is a kind of suicide pact. And here is the little miracle that shows we still have more than our share of luck: at exactly the same time when it became clear that we have to stop burning fossil fuels, a wide variety of other technologies for generating energy became available. We are truly blessed.

So now we have to manage the transition, and we have about half a century to complete the job. Most of the changeover has got to come in the next twenty years, and we need to have completely decarbonized our economies by 2050. In the meantime, we have to keep the global average temperature from passing the plus-two-degrees-Celsius boundary no matter what the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere is doing, and in the longer run we need to get the carbon dioxide down to 350 parts per million. That won't be easy, but it is the sort of task at which industrial societies excel.

We just barely scraped through the mid-term exam in the last century: we acquired the ability to destroy our civilization directly, by war, and we managed not to use it. Now it's the final exam, with the whole environment that our civilization depends on at stake. It's not just about knowledge and technical ability; it is also about self-restraint and the ability to cooperate. Grown-up values, if you like. How fortunate that we should be set such a test at a point in our history where we have at least some chance of passing it. And how interesting the long future that stretches out beyond it will be, if we do pass.

***************************************************************************

The Baruch Plan, Bernard Baruch, June 14 1946.

My Fellow Members of the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, and My Fellow Citizens of the World:

We are here to make a choice between the quick and the dead.

That is our business.

Behind the black portent of the new atomic age lies a hope which, seized upon with faith, can work our salvation. If we fail, then we have damned every man to be the slave of Fear. Let us not deceive ourselves: We must elect World Peace or World Destruction.

Science has torn from nature a secret so vast in its potentialities that our minds cower from the terror it creates. Yet terror is not enough to inhibit the use of the atomic bomb. The terror created by weapons has never stopped man from employing them. For each new weapon a defense has been produced, in time. But now we face a condition in which adequate defense does not exist.

Science, which gave us this dread power, shows that it can be made a giant help to humanity, but science does not show us how to prevent its baleful use. So we have been appointed to obviate that peril by finding a meeting of the minds and the hearts of our peoples. Only in the will of mankind lies the answer.

It is to express this will and make it effective that we have been assembled. We must provide the mechanism to assure that atomic energy is used for peaceful purposes and preclude its use in war. To that end, we must provide immediate, swift, and sure punishment of those who violate the agreements that are reached by the nations. Penalization is essential if peace is to be more than a feverish interlude between wars. And, too, the United Nations can prescribe individual responsibility and punishment on the principles applied at Nuremberg by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the United Kingdom, France and the United States - a formula certain to benefit the world's future.

In this crisis, we represent not only our governments but, in a larger way, we represent the peoples of the world. We must remember that the peoples do not belong to the governments but that the governments belong to the peoples. We must answer their demands; we must answer the world's longing for peace and security.

In that desire the United States shares ardently and hopefully. The search of science for the absolute weapon has reached fruition in this country. But she stands ready to proscribe and destroy this instrument - to lift its use from death to life - if the world will join in a pact to that end.

In our success lies the promise of a new life, freed from the heart-stopping fears that now beset the world. The beginning of victory for the great ideals for which millions have bled and died lies in building a workable plan. Now we approach fulfillment of the aspirations of mankind. At the end of the road lies the fairer, better, surer life we crave and mean to have.

Only by a lasting peace are liberties and democracies strengthened and deepened. War is their enemy. And it will not do to believe that any of us can escape war's devastation. Victor, vanquished, and neutrals alike are affected physically, economically and morally.

Against the degradation of war we can erect a safeguard. That is the guerdon for which we reach. Within the scope for the formula we outline here there will be found, to those who seek it, the essential elements of our purpose. Others will see only emptiness. Each of us carries his own mirror in which is reflected hope - or determined desperation -courage or cowardice.

There is a famine throughout the world today. It starves men's bodies. But there is a greater famine - the hunger of men's spirit. That starvation can be cured by the conquest of fear, and the substitution of hope, from which springs faith - faith in each other, faith that we want to work together toward salvation, and determination that those who threaten the peace and safety shall be punished.

The peoples of these democracies gathered here have a particular concern with our answer, for their peoples hate war. They will have a heavy exaction to make of those who fail to provide an escape. They are not afraid of an internationalism that protects; they are unwilling to be fobbed off by mouthings about narrow sovereignty, which is today's phrase for yesterday's isolation.

The basis of a sound foreign policy, in this new age, for all the nations here gathered, is that anything that happens, no matter where or how, which menaces the peace of the world, or the economic stability, concerns each and all of us.

That roughly, may be said to be the central theme of the United Nations. It is with that thought we begin consideration of the most important subject that can engage mankind - life itself.

Let there be no quibbling about the duty and the responsibility of this group and of the governments we represent. I was moved, in the afternoon of my life, to add my effort to gain the world's quest, by the broad mandate under which we were created. The resolution of the General Assembly, passed January 24, 1946 in London reads:

Section V. Terms of References of the CommissionOur mandate rests, in text and spirit, upon the outcome of the Conference in Moscow of Messrs Molotov of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Bevin of the United Kingdom, and Byrnes of the United States of America. The three Foreign Ministers on December 27, 1945 proposed the establishment of this body.

The Commission shall proceed with the utmost despatch and enquire into all phases of the problem, and make such recommendations from time to time with respect to them as it finds possible. In particular the Commission shall make specific proposals:1. For extending between all nations the exchange of basic scientific information for peaceful ends;The work of the Commission should proceed by separate stages, the successful completion of each of which will develop the necessary confidence of the world before the next stage is undertaken. ...

2. For control of atomic energy to the extent necessary to ensure its use only for peaceful purposes;

3. For the elimination from national armaments of atomic weapons and of all other major weapons adaptable to mass destruction;

4. For effective safeguards by way of inspection and other means to protect complying States against the hazards of violations and evasions.

Their action was animated by a preceding conference in Washington on November 15, 1945, when the President of the United States, associated with Mr Attlee, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and Mr Mackenzie King, Prime Minister of Canada, stated that international control of the whole field of atomic energy was immediately essential. They proposed the formation of this body. In examining that source, the Agreed Declaration, it will be found that the fathers of the concept recognized the final means of world salvation - the abolition of war. Solemnly they wrote:

We are aware that the only complete protection for the civilized world from the destructive use of scientific knowledge lies in the prevention of war. No system of safeguards that can be devised will of itself provide an effective guarantee against production of atomic weapons by a nation bent on aggression. Nor can we ignore the possibility of the development of other weapons, or of new methods of warfare, which may constitute as great a threat to civilization as the military use of atomic energy.Through the historical approach I have outlined, we find ourselves here to test if man can produce, through his will and faith, the miracle of peace, just as he has, through science and skill, the miracle of the atom.

The United States proposes the creation of an International Atomic Development Authority, to which should be entrusted all phases of the development and use of atomic energy, starting with the raw material and including:

1. Managerial control or ownership of all atomic-energy, activities potentially dangerous to world security.I offer this as a basis for beginning our discussion.

2. Power to control, inspect, and license all other atomic activities.

3. The duty of fostering the beneficial uses of atomic energy.

4. Research and development responsibilities of an affirmative character intended to put the Authority in the forefront of atomic knowledge and thus to enable it to comprehend, and therefore to detect, misuse of atomic energy. To be effective, the Authority must itself be the world's leader in the field of atomic knowledge and development and thus supplement its legal authority with the great power inherent in possession of leadership in knowledge.

But I think the peoples we serve would not believe - and without faith nothing counts - that a treaty, merely outlawing possession or use of the atomic bomb, constitutes effective fulfillment of the instructions to this Commission. Previous failures have been recorded in trying the method of simple renunciation, unsupported by effective guaranties of security and armament limitation. No one would have faith in that approach alone.

Now, if ever, is the time to act for the common good. Public opinion supports a world movement toward security. If I read the signs aright, the peoples want a program not composed merely of pious thoughts but of enforceable sanctions - an international law with teeth in it.

We of this nation, desirous of helping to bring peace to the world and realizing the heavy obligations upon us arising from our possession of the means of producing the bomb and from the fact that it is part of our armament, are prepared to make our full contribution toward effective control of atomic energy.

When an adequate system for control of atomic energy, including the renunciation of the bomb as a weapon, has been agreed upon and put into effective operation and condign punishments set up for violations of the rules of control which are to be stigmatized as international crimes, we propose that:

1. Manufacture of atomic bombs shall stop;Let me repeat, so as to avoid misunderstanding: My country is ready to make its full contribution toward the end we seek, subject of course to our constitutional processes and to an adequate system of control becoming fully effective, as we finally work it out.

2. Existing bombs shall be disposed of pursuant to the terms of the treaty; and

3. The Authority shall be in possession of full information as to the know-how for the production of atomic energy.

Now as to violations: In the agreement, penalties of as serious a nature as the nations may wish and as immediate and certain in their execution as possible should be fixed for:

1. Illegal possession or use of an atomic bomb;It would be a deception, to which I am unwilling to lend myself, were I not to say to you and to our peoples that the matter of punishment lies at the very heart of our present security system. It might as well be admitted, here and now, that the subject goes straight to the veto power contained in the Charter of the United Nations so far as it relates to the field of atomic energy. The Charter permits penalization only by concurrence of each of the five great powers - the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the United Kingdom, China, France, and the United States.

2. Illegal possession, or separation, of atomic material suitable for use in an atomic bomb;

3. Seizure of any plant or other property belonging to or licensed by the Authority;

4. Willful interference with the activities of the Authority;

5. Creation or operation of dangerous projects in a manner contrary to, or in the absence of, a license granted by the international control body.

I want to make very plain that I am concerned here with the veto power only as it affects this particular problem. There must be no veto to protect those who violate their solemn agreements not to develop or use atomic energy for destructive purposes.

The bomb does not wait upon debate. To delay may be to die. The time between violation and preventive action or punishment would be all too short for extended discussion as to the course to be followed.

As matters now stand several years may be necessary for another country to produce a bomb, de novo. However, once the basic information is generally known, and the Authority has established producing plants for peaceful purposes in the several countries, an illegal seizure of such a plant might permit a malevolent nation to produce a bomb in 12 months, and if preceded by secret preparation and necessary facilities perhaps even in a much shorter time. The time required - the advance warning given of the possible use of a bomb - can only be generally estimated but obviously will depend upon many factors, including the success with which the Authority has been able to introduce elements of safety in the design of its plants and the degree to which illegal and secret preparation for the military use of atomic energy will have been eliminated. Presumably

no nation would think of starting a war with only one bomb.3.

This shows how imperative speed is in detecting and penalizing violations.

The process of prevention and penalization - a problem of profound statecraft - is, as I read it, implicit in the Moscow statement, signed by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the United States and the United Kingdom a few months ago.