Up, Down, Appendices, Postscript.

Brian Gable's cartoons appear regularly in the Globe - one of the few remaining high points there.

Brian Gable's cartoons appear regularly in the Globe - one of the few remaining high points there.I found the Trussels at Politics Daily. They are from Texas: Robert Trussell, a theater critic for the Kansas City Star, from Kingsville; and his wife, Donna, a journalist who grew up in Dallas.

So ... Texans. The last cartoon is telling. Their caricature of Obama is interesting - I like those Betty Boop lips; but what gets my attention are the (three) issues that concern them: 1. End the wars, 2. Redistribute wealth, and 3. Close Guantanamo.

Seems a strange selection ... (?) ... must be something to do with Texas.

Seems a strange selection ... (?) ... must be something to do with Texas.Then there is this Liberal 'attack' ad. "DECEIT, ABUSE, CONTEMPT," they say.

There is no doubt at all about the deceit and contempt. But it leaves me wondering just exactly what constitutes abuse to a cringeing dog? To do with the Liberals wanting to see things in threes maybe? Some strange k-k-Canadian k-k-Cabbala sensibility? Is that it?

Photos of L'Afua by Sylvie Blum.

Photos of L'Afua by Sylvie Blum.I posted these pictures last week - and then at the last moment took them down. What I said (

So I clipped them out, but after a week of thinking about it ... I still don't have much to say beyond that.

So I clipped them out, but after a week of thinking about it ... I still don't have much to say beyond that.There is nothing pornographic here, just because she is naked. She is admirable: strong, self-posessed, powerful, expressive, fearless ... a better example for 10 year-old girls such as Maria Aragon (maybe?) than some Lady Gaga zero. I would say so, for my daughter and grand-daughters at least.

Who can say? No certainty here. Nothing left but images plucked from the Internet and wild guesses.

I will spare you the hand-wringing over the human victims of this tragedy - in their tens and hundreds of thousands. Just consider that it is snowing in Japan these days ...

I will spare you the hand-wringing over the human victims of this tragedy - in their tens and hundreds of thousands. Just consider that it is snowing in Japan these days ...  In the NYT they call it a 'Dearth of Candor' ... a smattering of political history, a hint of capitalist command & control, bureaucratic structures failing under stress.

In the NYT they call it a 'Dearth of Candor' ... a smattering of political history, a hint of capitalist command & control, bureaucratic structures failing under stress.Germany has immediately hit the pause button. The United States, UK, Canada, and Ontario have immediately begun weaseling. K-k-Canadians are so forthright & candid, you have to love them for it ... up pops this Globe editorial, seconded by no less than George Monbiot, presenting the self-interested bourgeois view in all of its gorgeous & egregious splendour. So we know exactly what they are thinking; or, since it's not thinking (obviously), exactly what they think they are thinking. The NYT editorial is more reserved, but is running down the same track - to be clear, that would be the 'to hell in a handbasket' track. You can hear the ghost of Gaia, James Lovelock, applauding. Even Gwynne Dyer is ditto-ing - admitting the intractable waste problem and then calling reservations about nuclear power 'superstition'. And here I thought Gwynne Dyer was a smart guy - I guess the fatness I saw when he shared the stage with Elizabeth May was what it looked like - fat.

Why do I say 'obviously' above? Simple. Because no one has any clear idea of what to do with the waste (after fifty and more years thinking about it). Doh!?

This model, anonymous [not, Oluwatoyin Pyne] too, but with a ring in her nose, is presented by Kwesi Abbensetts. What does she think about it all I wonder?

This model, anonymous [not, Oluwatoyin Pyne] too, but with a ring in her nose, is presented by Kwesi Abbensetts. What does she think about it all I wonder?But really, most of us know next to diddley-squat nothing. I cannot make sense of millisieverts (mSv) and millisieverts per hour and Grays (Gy) and Roentgens (R, rem) and the rest, or the subtle differences between Iodine-131 and Cesium-137, or where the Plutonium-238 thru 244 goes, or where the steel goes when they get around to decommissioning - India one presumes, for dilution and recycling, or maybe into bullets (to replace spent Uranium, is that it?).

Radiation levels in Tokyo are 20 times 'normal' background. What does that mean? Radiation levels in Lake Ontario are double what they were 10 (?) years ago. What does that mean?

Radiation levels in Tokyo are 20 times 'normal' background. What does that mean? Radiation levels in Lake Ontario are double what they were 10 (?) years ago. What does that mean?At first it was the Japanese bureaucrats & industrialists & politicians who were saying nothing about what they probably did not know anyway; now it is the Americans with their more-or-less accurate spy-plane & satellite data who are not saying much.

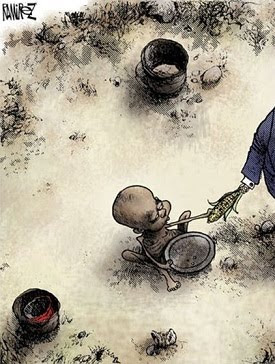

Japanese spinach is increasingly radioactive apparently - Lookout Popeye!

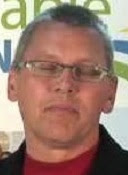

Oh and here's Ted Gruetzner of Ontario Power Generation (OPG) who tells us there is no reason for concern, none at all, none whatsoever, over the swimming pool-full of Tritium laced water they accidentally dumped into Lake Ontario this week (last week?). And they're so sorry they waited so long to tell us. By my count this kind of 'accident' happens once or twice every year - every day according to some reports.

Oh and here's Ted Gruetzner of Ontario Power Generation (OPG) who tells us there is no reason for concern, none at all, none whatsoever, over the swimming pool-full of Tritium laced water they accidentally dumped into Lake Ontario this week (last week?). And they're so sorry they waited so long to tell us. By my count this kind of 'accident' happens once or twice every year - every day according to some reports.

And this is Don Terry, another spokesman for OPG, saying about the same ... "There's no problem here ev'ree-budee, nope nope nope. Please put down the weapons, clear the area, and return to your houses."

And this is Don Terry, another spokesman for OPG, saying about the same ... "There's no problem here ev'ree-budee, nope nope nope. Please put down the weapons, clear the area, and return to your houses."You can catch their act here at CTV, and on YouTube.

How can anyone believe a word these people say? What planet do they inhabit? What fucking language is it that are they speaking?

Smug Spineless & Supercilious Twits!

Smug Spineless & Supercilious Twits!Dipshit Mealy-Mouthed Weasels!

(dipshit and mealy-mouthed are in the OED in case you don't know what these words mean)

And yet another unit enters the fray; what is a Becquerel (Bq)? And how many of them per litre am I getting in my drinking water?

Wikipedia tells me "Naturally occurring tritium is extremely rare on Earth, where trace amounts are formed by the interaction of the atmosphere with cosmic rays." So how then did we get to have an 'acceptable' level of release of Tritium other than damn well zero? How does the 'acceptable limit' get to be 7,000 bequerels when there used to be just about absolutely no Tritium in the water at all?

Doh!? ... Doh¡¿ WTF?

When the shit hits the fan they will all just say it was "an unprecedented sequence of natural events" - God did it.

A-and the last word on nuclear risks goes to The Onion.

Brett Gundlock made portraits of twenty of the G20 prisoners arrested last summer. Ten of them are displayed at the Communication Art Gallery, a tiny room near the corner of Bathurst and Harbord streets in Toronto watched over by a pleasant & articulate young woman - worth a visit.

Brett Gundlock made portraits of twenty of the G20 prisoners arrested last summer. Ten of them are displayed at the Communication Art Gallery, a tiny room near the corner of Bathurst and Harbord streets in Toronto watched over by a pleasant & articulate young woman - worth a visit.About a thousand people were plucked off the streets of this city last summer, almost every last one of them entirely innocent. They were dragged to a (temporary?) concentration camp by thugs disguised as police officers. Eight months ago, nine months ago, and Bill Blair, mein scheisse kopf führer Chief of Police, still has damn-all nothing to say about it ... here's a question for y'all: Just how long does gestation take in k-k-Canada?

Catarina Efigénia Sabino Eufémia was murdered by police in 1954. Who cares? It was a long time ago. The son of a bitch who did it, a lieutenant no less, was never tried.

Catarina Efigénia Sabino Eufémia was murdered by police in 1954. Who cares? It was a long time ago. The son of a bitch who did it, a lieutenant no less, was never tried.I am left wondering ... if all of it simply means nothing at all. I can't find a way yet to walk around Suzuki's remark that we have been at it for fifty years and things are getting worse.

Whatever.

I watched V For Vendetta again. I didn't get it the first time, nor this time neither; it is not intended to be 'gotten' maybe, if indeed anything is intended. How skinny is Natalie Portman at all? But I bet she is a plump little butterball baleboste by the time she is 60.

"If he will not other wayes confesse, the gentle tortures are to be first usid unto him, & sic per gradus ad ima tenditur," (King James I, referring to Guy Fawkes, November 1605) and "A penny for the Old Guy," (T.S. Eliot, The Hollow Men, 1925, referring to god knows what.)

This poem has been posted here before, but since it seems to require 15 minutes or so to find using the state-of-the-art search tools provided ... here it is again:

| Nothing has been broken though one of the links of the chain is a blue butterfly Here he was attacked They smiled as they came and retired baffled with blue dust The banks so familiar with metal they made for the wings The thick vaults fluttered The pretty girls advanced their fingers cupped They bled from the mouth as though struck The jury asked for pity and touched and were electrocuted by the blue antennae A thrust at any link might have brought him down but each of you aimed at the blue butterfly | Nada se partiu ainda que um dos elos da corrente fosse uma borboleta azul Aqui o cercaram Sorriam ao chegar e em retirada confundidos pela poeira azul Mesmo os bancos tão íntimos do metal que usaram nas asas suas espessas arcadas estremeceram Lindas jovens avançavam seus dedos como ventosas Suas bocas sangravam como se estivessem feridas O júri pedia clemencia tocava e era eletrocutado pelas antenas azuis Um ataque em qualquer elo poderia tê-lo abatido mas cada um de vocês mirava a borboleta azul |

I have posted the tensegrity photograph once or twice before too - it turns out to have been taken by Hiroshi Watanabe (here), and a copy of the contact print showed up as well. Taken in Parque El Arbolito, Quito, Ecuador. Here is another photo of the structure.

I have posted the tensegrity photograph once or twice before too - it turns out to have been taken by Hiroshi Watanabe (here), and a copy of the contact print showed up as well. Taken in Parque El Arbolito, Quito, Ecuador. Here is another photo of the structure. Aretha is still the queen of soul; and if you listen carefully you will hear the "ree ree ree ree, ree ree ree ree" there in the background, not in triplets ... ok.

Aretha is still the queen of soul; and if you listen carefully you will hear the "ree ree ree ree, ree ree ree ree" there in the background, not in triplets ... ok.Be well gentle reader.

Postscript:

There is news from Brasil (here and here) ... but it will have to wait.

In the meantime, the New York Times is getting ready to charge for access: $15/month by the looks of it. A watershed moment. I think I will pay the price.

In the meantime, the New York Times is getting ready to charge for access: $15/month by the looks of it. A watershed moment. I think I will pay the price.The Globe and Mail has sunk so low, particularly on the science-related issues that matter most to me; renewable energy, climate change, nuclear energy; and while the NYT may very well be no less bourgeois in its collective sensibility ... they do seem to be capable of moderating comments effectively. I wonder how they do it?

Time and well past time for the Globe to take down this masthead: "The subject who is truly loyal to the Chief Magistrate will neither advise nor submit to arbitrary measures." Junius.

Time and well past time for the Globe to take down this masthead: "The subject who is truly loyal to the Chief Magistrate will neither advise nor submit to arbitrary measures." Junius.This is not a sudden decision; arbitrary maybe but not sudden. I stopped subscribing several years ago - when they fired Edward Greenspon. And I have noted the departures of such stalwarts as Rick Salutin and more-or-less humble citizens such as Alan Burke.

They should lose the masthead; but in the same way that I always viewed Richard Nixon as a perfectly fitting President for the United States, a kind of epitome, I think they should keep the sobriquet k-k-"Canada's National Newspaper" - I'll give Phillip Crawley & John Stackhouse just exactly that much.

Appendices:

1. Dearth of Candor From Japan’s Leadership, Hiroko Tabuchi & Ken Belson & Norimitsu Onishi, March 16 2011.

2. The nuclear risk merits actions, but not global shutdowns, Globe Editorial, March 14 2011.

3. Japan nuclear crisis should not carry weight in atomic energy debate, George Monbiot, March 16 2011.

4. Nuclear Energy Advocates Insist U.S. Reactors Completely Safe Unless Something Bad Happens, The Onion, March 17 2011.

5. Early Questions After Japan, NYT Editorial, March 17 2011.

6. Nuclear power debate amid Japan crisis ruled by superstition, Gwynne Dyer, March 17 2011.

Dearth of Candor From Japan’s Leadership, Hiroko Tabuchi & Ken Belson & Norimitsu Onishi, March 16 2011.

TOKYO — With all the euphemistic language on display from officials handling Japan’s nuclear crisis, one commodity has been in short supply: information.

When an explosion shook one of many stricken reactors at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant on Saturday, power company officials initially offered a typically opaque, and understated, explanation.

“A big sound and white smoke” were recorded near Reactor No. 1, the plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power, announced in a curt memo. The matter “was under investigation,” it added.

Foreign nuclear experts, the Japanese press and an increasingly angry and rattled Japanese public are frustrated by government and power company officials’ failure to communicate clearly and promptly about the nuclear crisis. Pointing to conflicting reports, ambiguous language and a constant refusal to confirm the most basic facts, they suspect officials of withholding or fudging crucial information about the risks posed by the ravaged Daiichi plant.

The sound and white smoke on Saturday turned out to be the first in a series of explosions that set off a desperate struggle to bring four reactors under control after their cooling systems were knocked out by the earthquake and tsunami.

Evasive news conferences followed uninformative briefings as the crisis intensified over the past five days. Never has postwar Japan needed strong, assertive leadership more — and never has its weak, rudderless system of governing been so clearly exposed. With earthquake, tsunami and nuclear crisis striking in rapid, bewildering succession, Japan’s leaders need skills they are not trained to have: rallying the public, improvising solutions and cooperating with powerful bureaucracies.

“Japan has never experienced such a serious test,” said Takeshi Sasaki, a political scientist at Gakushuin University. “At the same time, there is a leadership vacuum.”

Politicians are almost completely reliant on Tokyo Electric Power, which is known as Tepco, for information, and have been left to report what they are told, often in unconvincing fashion.

In a telling outburst, the prime minister, Naoto Kan, berated power company officials for not informing the government of two explosions at the plant early Tuesday morning.

“What in the world is going on?” Mr. Kan said in front of journalists, complaining that he saw television reports of the explosions before he had heard about them from the power company. He was speaking at the inauguration of a central response center of government ministers and Tepco executives that he set up and pointedly said he would command.

The chief of the International Atomic Energy Agency said late Tuesday in a press conference in Vienna that his agency was struggling to get timely information from Japan about its failing reactors, which has resulted in agency misstatements.

“I am asking the Japanese counterparts to further strengthen, to facilitate, communication,” said the agency’s chief, Yukiya Amano. A diplomat in Vienna familiar with the agency’s operations echoed those sentiments.

“It’s so frustrating to try to get good information” from the Japanese, the diplomat said, speaking on the condition of anonymity so as not to antagonize officials there.

The less-than-straight talk is rooted in a conflict-averse culture that avoids direct references to unpleasantness. Until recently, it was standard practice not to tell cancer patients about their diagnoses, ostensibly to protect them from distress. Even Emperor Hirohito, when he spoke to his subjects for the first time to mark Japan’s surrender in World War II, spoke circumspectly, asking Japanese to “endure the unendurable.”

There are also political considerations. In the only nation that has endured an atomic bomb attack, acute sensitivity about radiation sickness may be motivating public officials to try to contain panic — and to perform political damage control. Left-leaning news outlets have long been skeptical of nuclear power and of its backers, and the mutual mistrust led power companies and their regulators to tightly control the flow of information about nuclear operations so as not to inflame a spectrum of opponents that includes pacifists and environmentalists.

“It’s a Catch-22,” said Kuni Yogo, a former nuclear power planner at Japan’s Science and Technology Agency. He said that the government and Tepco “try to disclose only what they think is necessary, while the media, which has an antinuclear tendency, acts hysterically, which leads the government and Tepco to not offer more information.”

The Japanese government has also decided to limit the flow of information to the public about the reactors, having concluded that too many briefings will distract Tepco from its task of bringing the reactors under control, said a senior nuclear industry executive.

At a Tepco briefing on Wednesday, tempers ran high among reporters. Their questions focused on the plumes of steam seen rising from Daiichi’s Reactor No. 3, but there were few answers.

“We cannot confirm,” an official insisted. “It is impossible for me to say anything at this point,” another said. And as always, there was an effusive apology: “We are so sorry for causing you bother.”

“There are too many things you cannot confirm!” one frustrated reporter replied in an unusually strong tone that perhaps signaled that ritual apologies had no place in a nuclear crisis.

Yukio Edano, the outspoken chief cabinet secretary, has been one voice of relative clarity. But at times, he has seemed unable to make sense of the fast-evolving crisis. And even he has spoken too ambiguously for foreign news media.

On Wednesday, Mr. Edano told a press conference that radiation levels had spiked because of smoke billowing from Reactor No. 3 at Fukushima Daiichi, and that all staff members would be temporarily moved “to a safe place.” When he did not elaborate, some foreign reporters, perhaps further confused by the English translator from NHK, the national broadcaster, interpreted his remarks as meaning that Tepco staff members were leaving the plant.

From CNN to The Associated Press to Al Jazeera, panicky headlines shouted that the Fukushima Daiichi plant was being abandoned, in stark contrast to the calm maintained by Japanese media, perhaps better at navigating the nuances of the vague comments.

After checking with nuclear regulators and Tepco itself, it emerged that the plant’s staff members had briefly taken cover indoors within the plant, but had in no way abandoned it.

The close links between politicians and business executives have further complicated the management of the nuclear crisis.

Powerful bureaucrats retire to better-paid jobs in the very industries they once oversaw, in a practice known as “amakudari.” Perhaps no sector had closer relations with regulators than the country’s utilities; regulators and the regulated worked hand in hand to promote nuclear energy, since both were keen to reduce Japan’s heavy reliance on fossil fuels.

Postwar Japan flourished under a system in which political leaders left much of the nation’s foreign policy to the United States and domestic affairs to powerful bureaucrats. Prominent companies operated with an extensive reach into personal lives; their executives were admired for their roles as corporate citizens.

But over the past decade or so, the bureaucrats’ authority has been greatly reduced, and corporations have lost both power and swagger as the economy has floundered.

Yet no strong political class has emerged to take their place. Four prime ministers have come and gone in less than four years; most political analysts had already written off the fifth, Mr. Kan, even before the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster.

Two years ago, Mr. Kan’s Japan Democratic Party swept out the virtual one-party rule of the Liberal Democratic Party, which had dominated Japanese political life for 50 years.

But the lack of continuity and inexperience in governing have hobbled Mr. Kan’s party. The only long-serving group within the government is the bureaucracy, which has been, at a minimum, mistrustful of the party.

“It’s not in their DNA to work with anybody other than the Liberal Democrats,” said Noriko Hama, an economist at Doshisha University.

Neither Mr. Kan nor the bureaucracy has had a hand in planning the rolling residential blackouts in the Tokyo region; the responsibility has been left to Tepco. Unlike the orderly blackouts in the 1970s, the current ones have been carried out with little warning, heightening the public anxiety and highlighting the lack of a trusted leader capable of sharing information about the scope of the disaster and the potential threats to people’s well-being.

“The mistrust of the government and Tepco was already there before the crisis, and people are even angrier now because of the inaccurate information they’re getting,” said Susumu Hirakawa, a professor of psychology at Taisho University.

But the absence of a galvanizing voice is also the result of the longstanding rivalries between bureaucrats and politicians, and between various ministries that tend to operate as fiefdoms.

“There’s a clear lack of command authority in the current government in Tokyo,” said Ronald Morse, who has worked in the Defense, Energy and State Departments in the United States and in two government ministries in Japan. “The magnitude of it becomes obvious at a time like this.”

The nuclear risk merits actions, but not global shutdowns, Globe Editorial, March 14 2011.

Practically alone among nations, the people of Japan know firsthand the terrible consequences of splitting the atom. As they grieve the thousands dead and the destroyed communities from another, natural, disaster, there are new concerns about nuclear energy – this time, from explosions and partial meltdowns at two of Japan’s nuclear power stations after Friday’s earthquake and tsunami. The situation at the Fukushima reactors is serious, even dire, but it ought not to sound the death knell of nuclear power, or delay the construction of new nuclear facilities.

With little hydroelectric capacity, depleted coal reserves, a still nascent wind and solar industry, a small land area and considerable energy needs, nuclear power makes a lot of sense for Japan. It can usually deliver on its promise of affordable, emissions-light energy to power 25 to 30 per cent of Japan’s electricity needs.

No energy source is perfect, and today it is easy to forget that extracting energy from other sources is demonstrably dangerous in the short run (witness the worldwide death toll, in the thousands annually, from explosions in coal mines and at oil and gas facilities), and, due to global warming exacerbated by the burning of fossil fuels, in the long run.

Even at Fukushima, Japan’s structural engineering skill was on display; it was the tsunami, and not the earthquake, that caused the most damage. But two critical planning oversights – the failure to provide for sufficient back-up power on- and off-site, and the placing of back-up power too close to the shoreline – appear to have contributed to the partial meltdown. Human error, in combination with the rare extremity of Friday’s events, is causing Japan’s nuclear crisis.

But it is important to note that, so far, nothing has happened that could not have been predicted. There are few “unknown unknowns” or unforeseeable risks; indeed, we know the deadly, pervasive risk of the spread of radioactive material, and that awareness is driving the massive containment effort. We just need to account for those risks better.

So rather than forsake nuclear power altogether, all nuclear nations should re-evaluate the risks most germane to their facilities. The situation in Japan is still terrifying and fluid. But it is a good time to recognize that nuclear power is neither a saviour nor an anathema, as proclaimed by competing evangelists. It is a necessary energy source, though not without great risks – and those risks come from both natural and human sources.

Japan nuclear crisis should not carry weight in atomic energy debate, George Monbiot, March 16 2011.

Nuclear power remains far safer than coal. The awful events in Fukushima must not spook governments considering atomic energy

The nuclear disaster unfolding in Japan is bad enough; the nuclear disaster unfolding in China could be even worse.

"What disaster?", you may ask. The decision taken today by the Chinese government to suspend approval of new atomic power plants. If this suspension were to become permanent, the power those plants would have produced is likely to be replaced by burning coal. While nuclear causes calamities when it goes wrong, coal causes calamities when it goes right, and coal goes right a lot more often than nuclear goes wrong. The only safe coal-fired plant is one which has broken down past the point of repair.

Before I go any further, and I'm misinterpreted for the thousandth time, let me spell out once again what my position is. I have not gone nuclear. But, as long as the following four conditions are met, I will no longer oppose atomic energy.

1. Its total emissions – from mine to dump – are taken into account, and demonstrate that it is a genuinely low-carbon option,

2. We know exactly how and where the waste is to be buried,

3. We know how much this will cost and who will pay,

4. There is a legal guarantee that no civil nuclear materials will be diverted for military purposes.

To these I'll belatedly add a fifth, which should have been there all along: no plants should be built in fault zones, on tsunami-prone coasts, on eroding seashores or those likely to be inundated before the plant has been decommissioned or any other places which are geologically unsafe. This should have been so obvious that it didn't need spelling out. But we discover, yet again, that the blindingly obvious is no guarantee that a policy won't be adopted.

I despise and fear the nuclear industry as much as any other green: all experience hath shown that, in most countries, the companies running it are a corner-cutting bunch of scumbags, whose business originated as a by-product of nuclear weapons manufacture. But, sound as the roots of the anti-nuclear movement are, we cannot allow historical sentiment to shield us from the bigger picture. Even when nuclear power plants go horribly wrong, they do less damage to the planet and its people than coal-burning stations operating normally.

Coal, the most carbon-dense of fossil fuels, is the primary driver of human-caused climate change. If its combustion is not curtailed, it could kill millions of times more people than nuclear power plants have done so far. Yes, I really do mean millions. The Chernobyl meltdown was hideous and traumatic. The official death toll so far appears to be 43 – 28 workers in the initial few months then a further 15 civilians by 2005. Totally unacceptable, of course; but a tiny fraction of the deaths for which climate change is likely to be responsible, through its damage to the food supply, its contribution to the spread of infectious diseases and its degradation of the quality of life for many of the world's poorest people.

Coal also causes plenty of other environmental damage, far worse than the side effects of nuclear power production: from mountaintop removal to acid rain and heavy metal pollution. An article in Scientific American points out that the fly ash produced by a coal-burning power plant "carries into the surrounding environment 100 times more radiation than a nuclear power plant producing the same amount of energy".

Of course it's not a straight fight between coal and nuclear. There are plenty of other ways of producing electricity, and I continue to place appropriate renewables above nuclear power in my list of priorities. We must also make all possible efforts to reduce consumption. But we'll still need to generate electricity, and not all renewable sources are appropriate everywhere. While producing solar power makes perfect sense in north Africa, in the UK, by comparison to both wind and nuclear, it's a waste of money and resources. Abandoning nuclear power as an option narrows our choices just when we need to be thinking as broadly as possible.

Several writers for the Guardian have made what I believe is an unjustifiable leap. A disaster has occurred in a plant that was appallingly sited in an earthquake zone; therefore, they argue, all nuclear power programmes should be abandoned everywhere. It looks to me as if they are jumping on this disaster as support for a pre-existing position they hold for other reasons. Were we to follow their advice, we would rule out a low-carbon source of energy, which could help us tackle the gravest threat the world now faces. That does neither the people nor the places of the world any favours.

Nuclear Energy Advocates Insist U.S. Reactors Completely Safe Unless Something Bad Happens, The Onion, March 17 2011.

WASHINGTON — Responding to the ongoing nuclear crisis in Japan, officials from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission sought Thursday to reassure nervous Americans that U.S. reactors were 100 percent safe and posed absolutely no threat to the public health as long as no unforeseeable system failure or sudden accident were to occur. "With the advanced safeguards we have in place, the nuclear facilities in this country could never, ever become a danger like those in Japan, unless our generators malfunctioned in an unexpected yet catastrophic manner, causing the fuel rods to melt down," said NRC chairman Gregory Jaczko, insisting that nuclear power remained a clean, harmless energy source that could only lead to disaster if events were to unfold in the exact same way they did in Japan, or in a number of other terrifying and totally plausible scenarios that have taken place since the 1950s. "When you consider all of our backup cooling processes, containment vessels, and contingency plans, you realize that, barring the fact that all of those safety measures could be wiped away in an instant by a natural disaster or electrical error, our reactors are indestructible." Jaczko added that U.S. nuclear power plants were also completely guarded against any and all terrorist attacks, except those no one could have predicted.

Early Questions After Japan, NYT Editorial, March 17 2011.

As Japan’s nuclear crisis unfolds, nations around the world are looking at the safety of their nuclear reactors — as they should. But most are also waiting until all the facts are in before deciding whether or how to change their nuclear plans. The Obama administration has vowed to learn from the Japanese experience and incorporate new safety approaches if needed.

That makes sense to us — so long as there is rigorous follow-through. The operator of the stricken plant, the Tokyo Electric Power Company, and the Japanese government have been disturbingly opaque about what is happening at the Fukushima Daiichi complex and about efforts to prevent a meltdown and the potential public threat.

That has deepened anxieties in Japan and around the world and led the United States government to take the extraordinary step of announcing that the damage to at least one of the crippled reactors may be far worse than Tokyo had admitted — and urging Americans there to move further away from the official safety perimeter.

Still, enough is known to begin raising questions about our own nuclear operations. We hope regulators and industry leaders are equally forthcoming about this country’s vulnerabilities and challenges.

One of the first questions is whether current evacuation plans are robust enough. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission requires plant operators to alert the public within a 10-mile radius if a dangerous plume of radioactivity will be heading their way, and local officials decide whether to order an evacuation. The American Embassy in Japan, based on advice from Washington regulators, has told Americans there to evacuate to a radius of about 50 miles from the Fukushima plant.

Why wouldn’t a worst-case accident here merit the same caution? The difficulty, of course, is that some plants — including Indian Point north of New York City — are within 50 miles of millions of people. Regulators will need to clarify this discrepancy or start coming up with more ambitious evacuation plans.

Regulators need to immediately review their safety analyses of two California plants, which, like the Fukushima plant, are located on the coast and near geological faults and might theoretically face the double calamity of an earthquake and tsunami.

The type of reactors used at the Fukushima plant — made by the General Electric Company, they are known as Mark 1 boiling-water reactors — have long been known to have weak containment systems. In Japan, they appear to have been ruptured by explosions of escaping hydrogen. American regulators will need to determine whether similar reactors in this country are vulnerable and whether modifications in newer versions have made them sufficiently safe.

The stricken Japanese complex housed six reactors in close proximity; explosions, fires and radiation spread damage among four of them and has made rescue efforts harder. Regulators will need to look at whether American nuclear plants with multiple reactors are vulnerable to the same cascading effects. In recent days, a new danger has emerged in the spent fuel pools adjacent to the reactors. At least one has apparently lost its cooling water and another is cracked and possibly losing water. If the fuel catches fire, it could spew radiation over a large area. Regulators here may need to expedite the removal of some spent fuel from pools to dry storage in casks.

So far, the all-important lesson would seem to be: have sufficient emergency power at hand to keep cooling water circulating in the reactors to prevent a meltdown.

The Japanese reactors seem to have survived one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded without major structural damage. The crisis developed because the plant lost electrical power from the grid and the tsunami knocked out its backup diesel generators. American regulators must ensure that all nuclear plants have enough mobile generators or other backup power in place if their first two lines of defense are disabled.

Nuclear power debate amid Japan crisis ruled by superstition, Gwynne Dyer, March 17 2011.

Suppose that a giant hydro dam had crumbled under the impact of the biggest earthquake in a century and sent a wave of water racing down some valley in northern Japan. Imagine that whole villages and towns had been swept away, and that 10,000 people were killed — an even worse death toll than that caused by the tsunami that hit the coastal towns.

Would there be a great outcry worldwide, demanding that reservoirs be drained and hydro dams shut down? Of course not. Do you think we are superstitious savages? We are educated, civilized people, and we understand the way that risk works.

Okay, another thought experiment. Suppose that three big nuclear power reactors were damaged in that same monster earthquake, leading to concerns about a meltdown and a massive release of radiation—a new Chernobyl. Everybody within a 20-kilometre radius of the plant was evacuated, but in the end there were only minor leakages of radiation, and nobody was killed.

Well, that was a pretty convincing demonstration of the safety of nuclear power, wasn’t it? Well, wasn’t it? You there in the loincloth, with the bone through your nose. Why are you looking so frightened? Is something wrong?

In Germany, tens of thousands of protesters demonstrated against nuclear power last Saturday (March 12), and Chancellor Angela Merkel suspended her policy of extending the life of the country’s nuclear power stations until 2036. She conceded that, following events in Japan, it was not possible to “go back to business as usual”, meaning that she may return to the original plan to close down all 17 of Germany’s nuclear power plants by 2020.

In Britain, energy secretary Chris Huhne took a more measured approach: “As Europe seeks to remove carbon based fuels from its economy, there is a long term debate about finding the right mix between nuclear energy and energy generated from renewable sources....The events of the last few days haven’t done the nuclear industry any favours.” I wouldn’t invest in the promised new generation of nuclear power plants in Britain either.

And in the United States, Congressmen Henry Waxman and Ed Markey (Democratic), who cosponsored the 2009 climate bill, called for hearings into the safety and preparedness of America’s nuclear plants, 23 of which have similar designs to the stricken Fukushima Daiichi plant in Japan.

The alleged “nuclear renaissance” of the past few years was always a bit of a mirage so far as the West was concerned. China and India have big plans for nuclear energy, with dozens of reactors under construction and many more planned. In the United States, by contrast, there was no realistic expectation that more than four to six new reactors would be built in the next decade even before the current excitements.

The objections to a wider use of nuclear power in the United States are mostly rational. Safety worries are a much smaller obstacle than concerns about cost and time: nuclear plants are enormously expensive, and they take the better part of a decade to license and build. Huge cost overruns are normal, and government aid, in the form of loan guarantees and insurance coverage for catastrophic accidents, is almost always necessary.

The cost of wind and solar power is steadily dropping, and the price of natural gas, the least noxious fossil-fuel alternative to nuclear power, has been in free fall. There is no need for a public debate in the United States on the desirability of more nuclear power: just let the market decide. In Europe, however, there is a real debate, and the wrong side is winning it.

The European debate has focussed on shutting down existing nuclear generating capacity, not installing more of it. The German and Swedish governments may be forced by public opinion to revive the former policy of phasing out all their nuclear power plants in the near future, even though that means postponing the shut-down of highly polluting coal-fired power plants. Other European governments face similar pressures.

It’s a bad bargain. Hundreds of miners die every year digging the coal out of the ground, and hundreds of thousands of other people die annually from respiratory diseases caused by the pollution created by burning it. In the long run, hundreds of millions may die from the global warming that is driven in large part by greenhouse emissions from coal-fired power plants. Yet people worry more about nuclear power.

It’s the same sort of mistaken assessment of risk that caused millions of Americans to drive long distances instead of flying in the months just after 9/11. There were several thousand excess road deaths, while nobody died in the airplanes that had been avoided as too dangerous. Risks should be assessed rationally, not emotionally.

And here’s the funny thing. So long as the problems at Fukushima Daiichi do not kill large numbers of people, the Japanese will not turn against nuclear power, which currently provides over 30 percent of their electricity and is scheduled to expand to 40 percent. Their islands get hit by more big earthquakes than anywhere else on Earth, and the typhoons roar in regularly off the Pacific. They understand about risk.

Down