or words fail us ...

or words fail us ...or words fail me, ok!?

Up, Down, Appendices.

What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet;

Romeo, Romeo & Juliet, II, ii.

Han-shan:

| My heart is like the autumn moon pure as a blue-green pool. No, this comparison sucks. How can I explain? | My heart is like the autumn moon perfectly bright in the deep green pool, nothing can compare with it. You tell me how it can be explained. | ||

| My mind is the autumn moon shining in the blue-green pool, reflecting, glistening, clear and pure ... There's nothing to compare it to, what else can I say? | My mind is like the autumn moon, Shining clearly in the green pool. There is nothing with which it compares. How shall I explain it? |

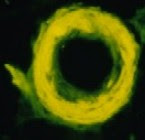

this all sort'a follows from Sengai's Medicine for the Eye in the last post, follows along to ensō/circle & zen and maybe to THX1138, George Lucas' first big feature in 1971 (download here or here if you like, or maybe you are influenced by the copyright issue? whatever) ... apparently Maggie McOmie got the part mostly because she was willing to shave her head - times have changed eh?

and please ... feel free to go on from here, from ensō to ... crop circles made by Martians or by the Yes Men or by the Merry Pranksters or by the Naska ... the sky's the limit eh? a veritable fugue ...

and please ... feel free to go on from here, from ensō to ... crop circles made by Martians or by the Yes Men or by the Merry Pranksters or by the Naska ... the sky's the limit eh? a veritable fugue ...so BP will sink to avoid swimming? a complete failure at working together despite all of those most directly involved from all parties having the highest levels of education and motivation (you would think) not to mention remuneration, even our Barack Obama being conned out of his Buddhist mindfulness into fractious bickering, and a symmetrical pattern is becoming more than a rhetorical figure for me personally, so as Gwynne Dyer once remarked, "the prospect of global disaster may help to concentrate people's minds," I like the phrase "concentrate people's minds"

but more than the billion or two that BP will spend on 'mitigation and remediation' (or whatever you want to call it) in the Gulf of Mexico and beyond, which is after all just a fraction of their annual profit, is the judgement of the stock market and the resulting devaluation of BP by up to 1/3 it looks like so far, this is much more, tens of billions wiped off the books - here's the point: where is the language that promotes constructive evaluation and action? and where is the language that describes this 'market' as the agglomeration of greedy over-fed bourgeois cowards that it truely is?

don't worry about Tony Hayward, he doesn't have to worry if they sack him, I'm sure he's got something stashed away somewhere very comfortable where everyone smiles.

don't worry about Tony Hayward, he doesn't have to worry if they sack him, I'm sure he's got something stashed away somewhere very comfortable where everyone smiles.

a-and then there's Alzheimer's (when it comes to losing words that is), aka 'La Bobera' in Spanish, a host of 'bob' words in Portuguese: bobeira, bobagem, bobo, boba, boboca ... and acronyms up the yin-yang: eFAD (Early-onset familial Alzheimer disease), LOAD (Late-onset Alzheimer disease), the list goes on ...

a-and then there's Alzheimer's (when it comes to losing words that is), aka 'La Bobera' in Spanish, a host of 'bob' words in Portuguese: bobeira, bobagem, bobo, boba, boboca ... and acronyms up the yin-yang: eFAD (Early-onset familial Alzheimer disease), LOAD (Late-onset Alzheimer disease), the list goes on ...do not fear gentle reader, I happen to know that after the fear and confusion, after the wandering, after the anger and rage, when language is long gone, at the end, at the very end there is a kind of peace, can be a kind of peace, a good kind of peace, completely mindless curled and cared for and sleeping on a cot in the soft winter sun ... so ...

does every child experience the feeling that it must be alien? is this what they mean by identity? is this the source of the archetype? is this the strength & appeal of Grimms' stories? I am not equipped to get very far into this, just following Wendell Berry's advice to 'practice ressurection' and so studying The Juniper Tree, both Grimms' story and the 1990 film with Björk Guðmundsdóttir (download here if you can be patient)

and following the threads that lead to the mysterious juniper stories in First Kings 18 & 19 and thence to T.S. Eliot's Ash Wednesday, "Teach us to care and not to care / Teach us to sit still," says Eliot, hearkening to the ensō maybe, and then, "Rose of memory / Rose of forgetfulness / Exhausted and life-giving / Worried reposeful / The single Rose / Is now the Garden / Where all loves end," and "Under a juniper-tree the bones sang, scattered and shining / We are glad to be scattered, we did little good to each other," and "Against the Word the unstilled world still whirled / About the centre of the silent Word."

and the concluding lines of his Four Quartets, 1943:

and the concluding lines of his Four Quartets, 1943:A condition of complete simplicityavoid fragmentation, avoid polarity, says Charles Taylor in Chapter 10 (and elsewhere) of The Malaise of Modernity, though I tend to agree with his own evaluation of it, being: "This sounds like saying that the way to succeed here is to succeed, which is true if perhaps unhelpful,"

(Costing not less than everything)

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flame are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

(and if these lines ain't sublime, then I dont know what is)

but what he is saying may be no more than embellishment on Revelations 3: "Be watchful, and strengthen the things which remain, that are ready to die," or as regurgitated by brother Bob, "When you gonna wake up and strengthen the things that remain?"

or even join with sister Björk in her Army Of Me (if such a thing is possible), ahh she is a beauty - always reminds me of my second wife, strong and uncompromising

or even join with sister Björk in her Army Of Me (if such a thing is possible), ahh she is a beauty - always reminds me of my second wife, strong and uncompromisingbut instead the k-k-Canadians will 'strengthen' copyright law, and let the drilling continue east of Newfoundland ... that's showing them our priorities eh? basically it's ANYTHING(!) but address climate change, and more here, and here's the report itself: A Climate Change Plan for the Purposes of the Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act, May 2010 - MAGGOTS!

Canadian copyright bill is out, Still too close to US DMCA, Spencer Dalziel, The Canadian Copyright Bill: Flawed But Fixable, Michael Geist, & Tory bill cracks down on copyright pirates, Steven Chase.

As BP disaster grows, Canada’s deepwater well faces scrutiny - Officials insist record-depth drilling off Newfoundland is safe, Shawn McCarthy,

& you can visit with Max Ruelokke P.Eng. who is the aforementioned 'official' who 'insists' and who is the chair of the CNLOPB (Canada-Newfoundland Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board) and who looks to me like he says just about what he is told to say, that despite ructions with Danny Williams over his installation a few years ago, ructions that elevated all the way to 'the courts!' eh?

and the beautiful young Somali girl (who speaks three languages) serving at the Tim Horton's tells me she is still in nursing school, just on summer holidays for now ... and she always lets me make her laugh ...

and the beautiful young Somali girl (who speaks three languages) serving at the Tim Horton's tells me she is still in nursing school, just on summer holidays for now ... and she always lets me make her laugh ... You find a flower half-buried in leaves,

You find a flower half-buried in leaves,And in your eye its very fate resides.

Loving beauty, you caress the bloom;

Soon enough, you'll sweep petals from the floor.

Terrible to love the lovely so,

To count your own years, to say "I'm old,"

To see a flower half-buried in leaves

And come face to face with what you are.

'come face to face with what you are' indeed, Han-shan with his scroll & Shih-te with his broom ... be well.

'come face to face with what you are' indeed, Han-shan with his scroll & Shih-te with his broom ... be well.Postscript:

sorry gentle reader, for making this post over-long but I wanted to remember the article by Margaret Atwood in Haaretz this week: The Shadow over Israel, she seems to me to be saying what she believes, like Mark Kingwell in the last post ... maybe this quality should not be so striking, maybe it is striking to me only because I am about 7/8 crazed ... I can't say ... but a bit of a time line may be in order, Atwood accepted the prize on May 11 though her essay was not (apparently) published in Haaretz until June 2, the Mavi Marmara was boarded on May 31, so Gaza flotilla drives Israel into a sea of stupidity on May 30 is before & Chosen, but Not Special on June 4 is after,

and to introduce the latest approximation by Clive Hamilton: Requiem for a Species or Why We Resist the Truth About Climate Change, which I will discuss when I have read all of it, in the meantime you can read the Preface, and an extract in The Guardian, and watch the book launch at ANU if you are so inclined.

Appendices:

1. Romeo's Soliloquy, Romeo & Juliet, Act II, Scene 2.

2. The Juniper Tree, Grimms' Fairy Tales.

3. The Malaise of Modernity, Chapter 10, Charles Taylor, Massey Lectures 1991.

4. Ash Wednesday, T.S. Eliot, 1930.

5. The numbers say it all: Canada is a climate-change miscreant, Jeffrey Simpson, June 3 2010.

6. Emissions reductions 10 times less than government’s projections: report, Gloria Galloway, June 3 2010.

7. The Shadow over Israel, Margaret Atwood, June 2 2010.

8. Gaza flotilla drives Israel into a sea of stupidity, Gideon Levy, May 30 2010.

9. Chosen, but Not Special, Michael Chabon, June 4 2010.

***************************************************************************

Romeo's Soliloquy, Romeo & Juliet, Act II, Scene 2.

He jests at scars that never felt a wound.

[Juliet appears above at a window]

But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief,

That thou her maid art far more fair than she:

Be not her maid, since she is envious;

Her vestal livery is but sick and green

And none but fools do wear it; cast it off.

It is my lady, O, it is my love!

O, that she knew she were!

She speaks yet she says nothing: what of that?

Her eye discourses; I will answer it.

I am too bold, 'tis not to me she speaks:

Two of the fairest stars in all the heaven,

Having some business, do entreat her eyes

To twinkle in their spheres till they return.

What if her eyes were there, they in her head?

The brightness of her cheek would shame those stars,

As daylight doth a lamp; her eyes in heaven

Would through the airy region stream so bright

That birds would sing and think it were not night.

See, how she leans her cheek upon her hand!

O, that I were a glove upon that hand,

That I might touch that cheek!

***************************************************************************

The Juniper Tree, Grimms' Fairy Tales.

It is now long ago, quite two thousand years, since there was a rich man who had a beautiful and pious wife, and they loved each other dearly. They had, however, no children, though they wished for them very much, and the woman prayed for them day and night, but still they had none.

Now there was a court-yard in front of their house in which was a juniper-tree, and one day in winter the woman was standing beneath it, paring herself an apple, and while she was paring herself the apple she cut her finger, and the blood fell on the snow. "Ah," said the woman, and sighed right heavily, and looked at the blood before her, and was most unhappy, "ah, if I had but a child as red as blood and as white as snow!" And while she thus spake, she became quite happy in her mind, and felt just as if that were going to happen. Then she went into the house and a month went by and the snow was gone, and two months, and then everything was green, and three months, and then all the flowers came out of the earth, and four months, and then all the trees in the wood grew thicker, and the green branches were all closely entwined, and the birds sang until the wood resounded and the blossoms fell from the trees, then the fifth month passed away and she stood under the juniper-tree, which smelt so sweetly that her heart leapt, and she fell on her knees and was beside herself with joy, and when the sixth month was over the fruit was large and fine, and then she was quite still, and the seventh month she snatched at the juniper-berries and ate them greedily, then she grew sick and sorrowful, then the eighth month passed, and she called her husband to her, and wept and said, "If I die then bury me beneath the juniper-tree." Then she was quite comforted and happy until the next month was over, and then she had a child as white as snow and as red as blood, and when she beheld it she was so delighted that she died.

Then her husband buried her beneath the juniper-tree, and he began to weep sore; after some time he was more at ease, and though he still wept he could bear it, and after some time longer he took another wife.

By the second wife he had a daughter, but the first wife's child was a little son, and he was as red as blood and as white as snow. When the woman looked at her daughter she loved her very much, but then she looked at the little boy and it seemed to cut her to the heart, for the thought came into her mind that he would always stand in her way, and she was for ever thinking how she could get all the fortune for her daughter, and the Evil One filled her mind with this till she was quite wroth with the little boy, and slapped him here and cuffed him there, until the unhappy child was in continual terror, for when he came out of school he had no peace in any place.

One day the woman had gone upstairs to her room, and her little daughter went up too, and said, "Mother, give me an apple." "Yes, my child," said the woman, and gave her a fine apple out of the chest, but the chest had a great heavy lid with a great sharp iron lock. "Mother," said the little daughter, "is brother not to have one too?" This made the woman angry, but she said, "Yes, when he comes out of school." And when she saw from the window that he was coming, it was just as if the Devil entered into her, and she snatched at the apple and took it away again from her daughter, and said, "Thou shalt not have one before thy brother." Then she threw the apple into the chest, and shut it. Then the little boy came in at the door, and the Devil made her say to him kindly, "My son, wilt thou have an apple?" and she looked wickedly at him. "Mother," said the little boy, "how dreadful you look! Yes, give me an apple." Then it seemed to her as if she were forced to say to him, "Come with me," and she opened the lid of the chest and said, "Take out an apple for thyself," and while the little boy was stooping inside, the Devil prompted her, and crash! she shut the lid down, and his head flew off and fell among the red apples. Then she was overwhelmed with terror, and thought, "If I could but make them think that it was not done by me!" So she went upstairs to her room to her chest of drawers, and took a white handkerchief out of the top drawer, and set the head on the neck again, and folded the handkerchief so that nothing could be seen, and she set him on a chair in front of the door, and put the apple in his hand.

After this Marlinchen came into the kitchen to her mother, who was standing by the fire with a pan of hot water before her which she was constantly stirring round. "Mother," said Marlinchen, "brother is sitting at the door, and he looks quite white and has an apple in his hand. I asked him to give me the apple, but he did not answer me, and I was quite frightened." "Go back to him," said her mother, "and if he will not answer thee, give him a box on the ear." So Marlinchen went to him and said, "Brother, give me the apple." But he was silent, and she gave him a box on the ear, on which his head fell down. Marlinchen was terrified, and began crying and screaming, and ran to her mother, and said, "Alas, mother, I have knocked my brother's head off!" and she wept and wept and could not be comforted. "Marlinchen," said the mother, "what hast thou done? but be quiet and let no one know it; it cannot be helped now, we will make him into black-puddings." Then the mother took the little boy and chopped him in pieces, put him into the pan and made him into black puddings; but Marlinchen stood by weeping and weeping, and all her tears fell into the pan and there was no need of any salt.

Then the father came home, and sat down to dinner and said, "But where is my son?" And the mother served up a great dish of black-puddings, and Marlinchen wept and could not leave off. Then the father again said, "But where is my son?" "Ah," said the mother, "he has gone across the country to his mother's great uncle; he will stay there awhile." "And what is he going to do there? He did not even say good-bye to me."

"Oh, he wanted to go, and asked me if he might stay six weeks, he is well taken care of there." "Ah," said the man, "I feel so unhappy lest all should not be right. He ought to have said good-bye to me." With that he began to eat and said, "Marlinchen, why art thou crying? Thy brother will certainly come back." Then he said, "Ah, wife, how delicious this food is, give me some more." And the more he ate the more he wanted to have, and he said, "Give me some more, you shall have none of it. It seems to me as if it were all mine." And he ate and ate and threw all the bones under the table, until he had finished the whole. But Marlinchen went away to her chest of drawers, and took her best silk handkerchief out of the bottom drawer, and got all the bones from beneath the table, and tied them up in her silk handkerchief, and carried them outside the door, weeping tears of blood. Then the juniper-tree began to stir itself, and the branches parted asunder, and moved together again, just as if some one was rejoicing and clapping his hands. At the same time a mist seemed to arise from the tree, and in the centre of this mist it burned like a fire, and a beautiful bird flew out of the fire singing magnificently, and he flew high up in the air, and when he was gone, the juniper-tree was just as it had been before, and the handkerchief with the bones was no longer there. Marlinchen, however, was as gay and happy as if her brother were still alive. And she went merrily into the house, and sat down to dinner and ate.

But the bird flew away and lighted on a goldsmith's house, and began to sing,

"My mother she killed me,

My father he ate me,

My sister, little Marlinchen,

Gathered together all my bones,

Tied them in a silken handkerchief,

Laid them beneath the juniper-tree,

Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful bird am I!"

The goldsmith was sitting in his workshop making a gold chain, when he heard the bird which was sitting singing on his roof, and very beautiful the song seemed to him. He stood up, but as he crossed the threshold he lost one of his slippers. But he went away right up the middle of the street with one shoe on and one sock; he had his apron on, and in one hand he had the gold chain and in the other the pincers, and the sun was shining brightly on the street. Then he went right on and stood still, and said to the bird, "Bird," said he then, "how beautifully thou canst sing! Sing me that piece again." "No," said the bird, "I'll not sing it twice for nothing! Give me the golden chain, and then I will sing it again for thee." "There," said the goldsmith, "there is the golden chain for thee, now sing me that song again." Then the bird came and took the golden chain in his right claw, and went and sat in front of the goldsmith, and sang,

"My mother she killed me,

My father he ate me,

My sister, little Marlinchen,

Gathered together all my bones,

Tied them in a silken handkerchief,

Laid them beneath the juniper-tree,

Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful bird am I!"

Then the bird flew away to a shoemaker, and lighted on his roof and sang,

"My mother she killed me,

My father he ate me,

My sister, little Marlinchen,

Gathered together all my bones,

Tied them in a silken handkerchief,

Laid them beneath the juniper-tree,

Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful bird am I!"

The shoemaker heard that and ran out of doors in his shirt sleeves, and looked up at his roof, and was forced to hold his hand before his eyes lest the sun should blind him. "Bird," said he, "how beautifully thou canst sing!" Then he called in at his door, "Wife, just come outside, there is a bird, look at that bird, he just can sing well." Then he called his daughter and children, and apprentices, boys and girls, and they all came up the street and looked at the bird and saw how beautiful he was, and what fine red and green feathers he had, and how like real gold his neck was, and how the eyes in his head shone like stars. "Bird," said the shoemaker, "now sing me that song again." "Nay," said the bird, "I do not sing twice for nothing; thou must give me something." "Wife," said the man, "go to the garret, upon the top shelf there stands a pair of red shoes, bring them down." Then the wife went and brought the shoes. "There, bird," said the man, "now sing me that piece again." Then the bird came and took the shoes in his left claw, and flew back on the roof, and sang,

"My mother she killed me,

My father he ate me,

My sister, little Marlinchen,

Gathered together all my bones,

Tied them in a silken handkerchief,

Laid them beneath the juniper-tree,

Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful bird am I!"

And when he had sung the whole he flew away. In his right claw he had the chain and the shoes in his left, and he flew far away to a mill, and the mill went, "klipp klapp, klipp klapp, klipp klapp," and in the mill sat twenty miller's men hewing a stone, and cutting, hick hack, hick hack, hick hack, and the mill went klipp klapp, klipp klapp, klipp klapp. Then the bird went and sat on a lime-tree which stood in front of the mill, and sang,

"My mother she killed me," -- Then one of them stopped working,

"My father he ate me." -- Then two more stopped working and listened to that,

"My sister, little Marlinchen," -- Then four more stopped,

"Gathered together all my bones,

Tied them in a silken handkerchief,"

Now eight only were hewing,

"Laid them beneath" -- Now only five,

"The juniper-tree," -- And now only one,

"Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful bird am I!" -- Then the last stopped also, and heard the last words. "Bird," said he, "how beautifully thou singest! Let me, too, hear that. Sing that once more for me."

"Nay," said the bird, "I will not sing twice for nothing. Give me the millstone, and then I will sing it again."

"Yes," said he, "if it belonged to me only, thou shouldst have it."

"Yes," said the others, "if he sings again he shall have it." Then the bird came down, and the twenty millers all set to work with a beam and raised the stone up. And the bird stuck his neck through the hole, and put the stone on as if it were a collar, and flew on to the tree again, and sang,

"My mother she killed me,

My father he ate me,

My sister, little Marlinchen,

Gathered together all my bones,

Tied them in a silken handkerchief,

Laid them beneath the juniper-tree,

Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful bird am I!"

And when he had done singing, he spread his wings, and in his right claw he had the chain, and in his left the shoes, and round his neck the millstone, and he flew far away to his father's house.

In the room sat the father, the mother, and Marlinchen at dinner, and the father said, "How light-hearted I feel, how happy I am!" "Nay," said the mother, "I feel so uneasy, just as if a heavy storm were coming." Marlinchen, however, sat weeping and weeping, and then came the bird flying, and as it seated itself on the roof the father said, "Ah, I feel so truly happy, and the sun is shining so beautifully outside, I feel just as if I were about to see some old friend again." "Nay," said the woman, "I feel so anxious, my teeth chatter, and I seem to have fire in my veins." And she tore her stays open, but Marlinchen sat in a corner crying, and held her plate before her eyes and cried till it was quite wet. Then the bird sat on the juniper tree, and sang,

"My mother she killed me," -- Then the mother stopped her ears, and shut her eyes, and would not see or hear, but there was a roaring in her ears like the most violent storm, and her eyes burnt and flashed like lightning,

"My father he ate me," -- "Ah, mother," says the man, "that is a beautiful bird! He sings so splendidly, and the sun shines so warm, and there is a smell just like cinnamon."

"My sister, little Marlinchen," -- Then Marlinchen laid her head on her knees and wept without ceasing, but the man said, "I am going out, I must see the bird quite close." "Oh, don't go," said the woman, "I feel as if the whole house were shaking and on fire." But the man went out and looked at the bird:

"Gathered together all my bones,

Tied them in a silken handkerchief,

Laid them beneath the juniper tree,

Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful bird am I!"

On this the bird let the golden chain fall, and it fell exactly round the man's neck, and so exactly round it that it fitted beautifully. Then he went in and said, "Just look what a fine bird that is, and what a handsome gold chain he has given me, and how pretty he is!" But the woman was terrified, and fell down on the floor in the room, and her cap fell off her head. Then sang the bird once more,

"My mother she killed me." -- "Would that I were a thousand feet beneath the earth so as not to hear that!"

"My father he ate me," -- Then the woman fell down again as if dead.

"My sister, little Marlinchen," -- "Ah," said Marlinchen, "I too will go out and see if the bird will give me anything," and she went out.

"Gathered together all my bones,

Tied them in a silken handkerchief,"

Then he threw down the shoes to her.

"Laid them beneath the juniper-tree,

Kywitt, kywitt, what a beautiful bird am I!"

Then she was light-hearted and joyous, and she put on the new red shoes, and danced and leaped into the house. "Ah," said she, "I was so sad when I went out and now I am so light-hearted; that is a splendid bird, he has given me a pair of red shoes!" "Well," said the woman, and sprang to her feet and her hair stood up like flames of fire, "I feel as if the world were coming to an end! I, too, will go out and see if my heart feels lighter." And as she went out at the door, crash! the bird threw down the millstone on her head, and she was entirely crushed by it. The father and Marlinchen heard what had happened and went out, and smoke, flames, and fire were rising from the place, and when that was over, there stood the little brother, and he took his father and Marlinchen by the hand, and all three were right glad, and they went into the house to dinner, and ate.

***************************************************************************

The Malaise of Modernity, Chapter 10, Charles Taylor, Massey Lectures 1991.

X AGAINST FRAGMENTATION

I argued in the preceding section that the institutions of a technological society don't ineluctably impose on us an ever-deepening hegemony of instrumental reason. But it is clear that left to themselves they have a tendency to push us in that direction. That is why the project has often been put forward of leaping out of these institutions altogether. One such dream was put forward by classical Marxism and enacted up to a point by Leninism. The goal was to do away with the market and bring the whole operation of the economy under the conscious control of the "associated producers," in Marx's phrase. ["Freedom in this field can only consist in socialized man, the associated producers, rationally regulating their interchange with Nature, bringing it under their common control, instead of being ruled by it as by the blind forces of Nature." Capital, vol. Ill (New York: International Publishers, 1967), p. 820.] Others cherish the hope that we might be able to do without the bureaucratic state.

It is now evident that these hopes are illusory. The collapse of Communist societies has finally made undeniable what many have felt all along: market mechanisms in some form are indispensable to an industrial society, certainly for its economic efficiency and probably also for its freedom. Some people in the West rejoice that this lesson has finally been learned and make the end of the Cold War a pretext for the celebration of their own utopia, a free society ordered through and through by impersonal market relations, with the state pushed into a limited residual role. But this is equally unrealistic. Stability, and hence efficiency, couldn't survive this massive withdrawal of government from the economy, and it is doubtful if freedom either could long survive the competitive jungle that a really wild capitalism would breed, with its uncompensated inequalities and exploitation.

What should have died along with communism is the belief that modern societies can be run on a single principle, whether that of planning under the general will or that of free-market allocations. Our challenge is actually to combine in some non-self-stultifying fashion a number of ways of operating, which are jointly necessary to a free and prosperous society but which also tend to impede each other: market allocations, state planning, collective provision for need, the defence of individual rights, and effective democratic initiative and control. In the short run, maximum market "efficiency" may be restricted by each of the other four modes; in the long run, even perhaps economic performance, but certainly justice and freedom, would suffer from their marginalization.

We can't abolish the market, but nor can we organize ourselves exclusively through markets. To restrict them may be costly; not to restrict them at all would be fatal. Governing a contemporary society is continually recreating a balance between requirements that tend to undercut each other, constantly finding creative new solutions as the old equilibria become stultifying. There can never be in the nature of the case a definitive solution. In this regard our political situation resembles the cultural predicament I described earlier. The continuing cultural struggle between different outlooks, different enframings of the key ideals of modernity, parallels on the institutional level the conflicting demands of the different but complementary ways we organize our common life: market efficiency may be dampened by collective provision through the welfare state; effective state planning may endanger individual rights; the joint operations of state and market may threaten democratic control.

But there is more than a parallel here. There is a connection, as I have indicated. The operation of market and bureaucratic state tends to strengthen the enframings that favour an atomist and instrumentalist stance to the world and others. That these institutions can never be simply abolished, that we have to live with them forever, has a lot to do with the unending, unresolvable nature of our cultural struggle.

Although there is no definitive victory, there is winning or losing ground. What this involves emerges from the example I mentioned in the previous section. There I noted that the battle of isolated communities or groups against ecological desolation was bound to be a losing one until such time as some common understanding and a common sense of purpose forms in society as a whole about the preservation of the environment. In other words, the force that can roll back the galloping hegemony of instrumental reason is (the right kind of) democratic initiative.

But this poses a problem, because the joint operation of market and bureaucratic state has a tendency to weaken democratic initiative. Here we return to the third area of malaise: the fear articulated by Tocqueville that certain conditions of modern society undermine the will to democratic control, the fear that people will come to accept too easily being governed by an "immense tutelary power."

Perhaps Tocqueville's portrait of a soft despotism, much as he means to distinguish it from traditional tyranny, still sounds too despotic in the traditional sense. Modern democratic societies seem far from this, because they are full of protest, free initiatives, and irreverent challenges to authority, and governments do in fact tremble before the anger and contempt of the governed, as these are revealed in the polls that rulers never cease taking.

But if we conceive Tocqueville's fear a little differently, then it does seem real enough. The danger is not actual despotic control but fragmentation — that is, a people increasingly less capable of forming a common purpose and carrying it out. Fragmentation arises when people come to see themselves more and more atomistically, otherwise put, as less and less bound to their fellow citizens in common projects and allegiances. They may indeed feel linked in common projects with some others, but these come more to be partial groupings rather than the whole society: for instance, a local community, an ethnic minority, the adherents of some religion or ideology, the promoters of some special interest.

This fragmentation comes about partly through a weakening of the bonds of sympathy, partly in a self-feeding way, through the failure of democratic initiative itself. Because the more fragmented a democratic electorate is in this sense, the more they transfer their political energies to promoting their partial groupings, in the way I want to describe below, and the less possible it is to mobilize democratic majorities around commonly understood programs and policies. A sense grows that the electorate as a whole is defenceless against the leviathan state; a well-organized and integrated partial grouping may, indeed, be able to make a dent, but the idea that the majority of the people might frame and carry through a common project comes to seem Utopian and naive. And so people give up. Already failing sympathy with others is further weakened by the lack of a common experience of action, and a sense of hopelessness makes it seem a waste of time to try. But that, of course, makes it hopeless, and a vicious circle is joined.

Now a society that goes this route can still be in one sense highly democratic, that is egalitarian, and full of activity and challenge to authority, as is evident if we look to the great republic to our south. Politics begins to take on a different mould, in the way I indicated above. One common purpose that remains strongly shared, even as the others atrophy, is that society is organized in the defence of rights. The rule of law and the upholding of rights are seen as very much the "American way," that is, as the objects of a strong common allegiance. The extraordinary reaction to the Watergate scandals, which ended up unseating a president, are a testimony to this.

In keeping with this, two facets of political life take on greater and greater saliency. First, more and more turns on judicial battles. The Americans were the first to have an entrenched bill of rights, augmented since by provisions against discrimination, and important changes have been made in American society through court challenges to legislation or private arrangements allegedly in breach of these entrenched provisions. A good example is the famous case of Brown vs the Board of Education, which desegregated the schools in 1954. In recent decades, more and more energy in the American political process is turning towards this process of judicial review. Matters that in other societies are determined by legislation, after debate and sometimes compromise between different opinions, are seen as proper subjects for judicial decision in the light of the constitution. Abortion is a case in point. Since Roe vs Wade in 1973 greatly liberalized the abortion law in the country, the effort of conservatives, now gradually coming to fruition, has been to stack the court in order to get a reversal. The result has been an astonishing intellectual effort, channelled into politics-as-judicial-review, that has made law schools the dynamic centres of social and political thought on American campuses; and also a series of titanic battles over what used to be the relatively routine — or at least non-partisan — matter of senatorial confirmation of presidential appointments to the Supreme Court.

Alongside judicial review, and woven into it, American energy is channelled into interest or advocacy politics. People throw themselves into single-issue campaigns and work fiercely for their favoured cause. Both sides in the abortion debate are good examples. This facet overlaps the previous one, because part of the battle is judicial, but it also involves lobbying, mobilizing mass opinion, and selective intervention in election campaigns for or against targeted candidates.

All this makes for a lot of activity. A society in which this goes on is hardly a despotism. But the growth of these two facets is connected, part effect and part cause, with the atrophy of a third, which is the formation of democratic majorities around meaningful programs that can then be carried to completion. In this regard, the American political scene is abysmal. The debate between the major candidates becomes ever more disjointed, their statements ever more blatantly self-serving, their communication consisting more and more of the now famous "sound bytes," their promises risibly unbelievable ("read my lips") and cynically unkept, while their attacks on their opponents sink to ever more dishonourable levels, seemingly with impunity. At the same time, in a complementary movement, voter participation in national elections declines, and has recently hit 50 per cent of the eligible population, far below that of other democratic societies.

Something can be said for, and perhaps a lot can be said against, this lopsided system. One might worry about its long-term stability, worry, that is, whether the citizen alienation caused by its less and less functional representative system can be compensated for by the greater energy of its special-interest politics. The point has also been made that this style of politics makes issues harder to resolve. Judicial decisions are usually winner-take-all; either you win or you lose. In particular, judicial decisions about rights tend to be conceived as all-or-nothing matters. The very concept of a right seems to call for integral satisfaction, if it's a right at all; and if not, then nothing. Abortion once more can serve as an example. Once you see it as the right of the fetus versus the right of the mother, there are few stopping places between the unlimited immunity of the one and the untrammelled freedom of the other. The penchant to settle things judicially, further polarized by rival special-interest campaigns, effectively cuts down the possibilities of compromise. [Mary Ann Glendon, Abortion and Divorce in Western Law (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987) has shown how this has made a difference to American decisions on this issue, as compared with those in comparable Western societies.] We might also argue that it makes certain issues harder to address, those that require a wide democratic consensus around measures that will also involve some sacrifice and difficulty. Perhaps this is part of the continuing American problem of coming to terms with their declining economic situation through some form of intelligent industrial policy. [I have raised the issue about democratic stability in "Cross-Purposes: The Liberal-Communitarian Debate/' in Nancy Rosenblum, ed., Liberalism and the Moral Life (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989). There is a good discussion of the slide towards this lop-sided package in American politics in Michael Sand el, "The Procedural Republic and the Unencumbered Self," in Political Theory 12 (February 1984). I have compared the American and Canadian systems in this respect in "Alternative Futures," in Alan Cairns and Cynthia Williams, eds., Constitutionalism, Citizenship and Society in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985). There is a good critique of this American political culture in B. Bellah et al., Habits of the Heart (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985) and The Good Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991).] But it also brings me to my point, which is that certain kinds of common projects become more difficult to enact where this kind of politics is dominant.

An unbalanced system such as this both reflects and entrenches fragmentation. Its spirit is an adversarial one in which citizen efficacy consists in being able to get your rights, whatever the consequences for the whole. Both judicial retrieval and single-issue politics operate from this stance and further strengthen it. Now what emerged above from the example of the recent fate of the ecological movement is that the only way to countervail the drift built into market and bureaucracy is through the formation of a common democratic purpose. But this is exactly what is difficult in a democratic system that is fragmented.

A fragmented society is one whose members find it harder and harder to identify with their political society as a community. This lack of identification may reflect an atomistic outlook, in which people come to see society purely instrumentally. But it also helps to entrench atomism, because the absence of effective common action throws people back on themselves. This is perhaps why one of the most widely held social philosophies in the contemporary United States is the procedural liberalism of neutrality that I mentioned earlier (in section II), and which combines quite smoothly with an atomist outlook.

But now we can also see that fragmentation abets atomism in another way. Because the only effective counter to the drift towards atomism and instrumentalism built into market and bureaucratic state is the formation of an effective common purpose through democratic action, fragmentation in fact disables us from resisting this drift. To lose the capacity to build politically effective majorities is to lose your paddle in mid-river. You are carried ineluctably downstream, which here means further and further into a culture enframed by atomism and instrumentalism.

The politics of resistance is the politics of democratic will-formation. As against those adversaries of technological civilization who have felt drawn to an elitist stance, we must see that a serious attempt to engage in the cultural struggle of our time requires the promotion of a politics of democratic empowerment. The political attempt to re-enframe technology crucially involves resisting and reversing fragmentation.

But how do you fight fragmentation? If s not easy, and there are no universal prescriptions. It depends very much on the particular situation. But fragmentation grows to the extent that people no longer identify with their political community, that their sense of corporate belonging is transferred elsewhere or atrophies altogether. And it is fed, too, by the experience of political powerlessness. And these two developments mutually reinforce each other. A fading political identity makes it harder to mobilize effectively, and a sense of helplessness breeds alienation. There is a potential vicious circle here, but we can see how it could also be a virtuous circle. Successful common action can bring a sense of empowerment and also strengthen identification with the political community.

This sounds like saying that the way to succeed here is to succeed, which is true if perhaps unhelpful. But we can say a little more. One of the important sources of the sense of powerlessness is that we are governed by large-scale, centralized, bureaucratic states. What can help mitigate this sense is decentralization of power, as Tocqueville saw. And so in general devolution, or a division of power, as in a federal system, particularly one based on the principle of subsidiarity, can be good for democratic empowerment. And this is the more so if the units to which power is devolved already figure as communities in the lives of their members.

In this respect, Canada has been fortunate. We have had a federal system, which has been prevented from evolving towards greater centralization on the model of the United States by our very diversity, while the provincial units generally correspond with regional societies with which their members identify. What we seem to have failed to do is create a common understanding that can hold these regional societies together, and so we face the prospect of another kind of loss of power, not that we experience when big government seems utterly unresponsive, but rather the fate of smaller societies living in the shadow of major powers.

This has ultimately been a failure to understand and accept the real nature of Canadian diversity. Canadians have been very good at accepting their own images of difference, but these have tragically failed to correspond to what is really there. It is perhaps not an accident that this failure comes just when an important feature of the American model begins to take hold in this country, in the form of judicial review around a charter of rights. In fact, it can be argued that the insistence on uniform application of a charter that had become one of the symbols of Canadian citizenship was an important cause of the demise of the Meech Lake agreement, and hence of the impending break-up of the country. [I have discussed this at greater length in "Shared and Divergent Values," in Ronald Watts and Douglas Brown, eds., Options for a New Canada (Kingston: Queen's University Press, 1991).]

But the general point I want to draw from this is the interweaving of the different strands of concern about modernity. The effective re-enframing of technology requires common political action to reverse the drift that market and bureaucratic state engender towards greater atomism and instrumentalism. And this common action requires that we overcome fragmentation and powerlessness — that is, that we address the worry that Tocqueville first defined, the slide in democracy towards tutelary power. At the same time, atomist and instrumentalist stances are prime generating factors of the more debased and shallow modes of authenticity, and so a vigorous democratic life, engaged in a project of re-enframing, would also have a positive impact here.

What our situation seems to call for is a complex, many-levelled struggle, intellectual, spiritual, and political, in which the debates in the public arena interlink with those in a host of institutional settings, like hospitals and schools, where the issues of enframing technology are being lived through in concrete form; and where these disputes in turn both feed and are fed by the various attempts to define in theoretical terms the place of technology and the demands of authenticity, and beyond that, the shape of human life and its relation to the cosmos.

But to engage effectively in this many-faceted debate, one has to see what is great in the culture of modernity, as well as what is shallow or dangerous. As Pascal said about human beings, modernity is characterized by grandeur as well as by misère. Only a view that embraces both can give us the undistorted insight into our era that we need to rise to its greatest challenge.

***************************************************************************

Ash Wednesday, T.S. Eliot, 1930.

I

Because I do not hope to turn again

Because I do not hope

Because I do not hope to turn

Desiring this man's gift and that man's scope

I no longer strive to strive towards such things

(Why should the agèd eagle stretch its wings?)

Why should I mourn

The vanished power of the usual reign?

Because I do not hope to know

The infirm glory of the positive hour

Because I do not think

Because I know I shall not know

The one veritable transitory power

Because I cannot drink

There, where trees flower, and springs flow, for there is nothing again

Because I know that time is always time

And place is always and only place

And what is actual is actual only for one time

And only for one place

I rejoice that things are as they are and

I renounce the blessèd face

And renounce the voice

Because I cannot hope to turn again

Consequently I rejoice, having to construct something

Upon which to rejoice

And pray to God to have mercy upon us

And pray that I may forget

These matters that with myself I too much discuss

Too much explain

Because I do not hope to turn again

Let these words answer

For what is done, not to be done again

May the judgement not be too heavy upon us

Because these wings are no longer wings to fly

But merely vans to beat the air

The air which is now thoroughly small and dry

Smaller and dryer than the will

Teach us to care and not to care Teach us to sit still.

Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death

Pray for us now and at the hour of our death.

II

Lady, three white leopards sat under a juniper-tree

In the cool of the day, having fed to sateity

On my legs my heart my liver and that which had been contained

In the hollow round of my skull. And God said

Shall these bones live? shall these

Bones live? And that which had been contained

In the bones (which were already dry) said chirping:

Because of the goodness of this Lady

And because of her loveliness, and because

She honours the Virgin in meditation,

We shine with brightness. And I who am here dissembled

Proffer my deeds to oblivion, and my love

To the posterity of the desert and the fruit of the gourd.

It is this which recovers

My guts the strings of my eyes and the indigestible portions

Which the leopards reject. The Lady is withdrawn

In a white gown, to contemplation, in a white gown.

Let the whiteness of bones atone to forgetfulness.

There is no life in them. As I am forgotten

And would be forgotten, so I would forget

Thus devoted, concentrated in purpose. And God said

Prophesy to the wind, to the wind only for only

The wind will listen. And the bones sang chirping

With the burden of the grasshopper, saying

Lady of silences

Calm and distressed

Torn and most whole

Rose of memory

Rose of forgetfulness

Exhausted and life-giving

Worried reposeful

The single Rose

Is now the Garden

Where all loves end

Terminate torment

Of love unsatisfied

The greater torment

Of love satisfied

End of the endless

Journey to no end

Conclusion of all that

Is inconclusible

Speech without word and

Word of no speech

Grace to the Mother

For the Garden

Where all love ends.

Under a juniper-tree the bones sang, scattered and shining

We are glad to be scattered, we did little good to each other,

Under a tree in the cool of day, with the blessing of sand,

Forgetting themselves and each other, united

In the quiet of the desert. This is the land which ye

Shall divide by lot. And neither division nor unity

Matters. This is the land. We have our inheritance.

III

At the first turning of the second stair

I turned and saw below

The same shape twisted on the banister

Under the vapour in the fetid air

Struggling with the devil of the stairs who wears

The deceitul face of hope and of despair.

At the second turning of the second stair

I left them twisting, turning below;

There were no more faces and the stair was dark,

Damp, jaggèd, like an old man's mouth drivelling, beyond

repair,

Or the toothed gullet of an agèd shark.

At the first turning of the third stair

Was a slotted window bellied like the figs's fruit

And beyond the hawthorn blossom and a pasture scene

The broadbacked figure drest in blue and green

Enchanted the maytime with an antique flute.

Blown hair is sweet, brown hair over the mouth blown,

Lilac and brown hair;

Distraction, music of the flute, stops and steps of the mind

over the third stair,

Fading, fading; strength beyond hope and despair

Climbing the third stair.

Lord, I am not worthy

Lord, I am not worthy

but speak the word only.

IV

Who walked between the violet and the violet

Whe walked between

The various ranks of varied green

Going in white and blue, in Mary's colour,

Talking of trivial things

In ignorance and knowledge of eternal dolour

Who moved among the others as they walked,

Who then made strong the fountains and made fresh the springs

Made cool the dry rock and made firm the sand

In blue of larkspur, blue of Mary's colour,

Sovegna vos

Here are the years that walk between, bearing

Away the fiddles and the flutes, restoring

One who moves in the time between sleep and waking, wearing

White light folded, sheathing about her, folded.

The new years walk, restoring

Through a bright cloud of tears, the years, restoring

With a new verse the ancient rhyme. Redeem

The time. Redeem

The unread vision in the higher dream

While jewelled unicorns draw by the gilded hearse.

The silent sister veiled in white and blue

Between the yews, behind the garden god,

Whose flute is breathless, bent her head and signed but spoke

no word

But the fountain sprang up and the bird sang down

Redeem the time, redeem the dream

The token of the word unheard, unspoken

Till the wind shake a thousand whispers from the yew

And after this our exile

V

If the lost word is lost, if the spent word is spent

If the unheard, unspoken

Word is unspoken, unheard;

Still is the unspoken word, the Word unheard,

The Word without a word, the Word within

The world and for the world;

And the light shone in darkness and

Against the Word the unstilled world still whirled

About the centre of the silent Word.

O my people, what have I done unto thee.

Where shall the word be found, where will the word

Resound? Not here, there is not enough silence

Not on the sea or on the islands, not

On the mainland, in the desert or the rain land,

For those who walk in darkness

Both in the day time and in the night time

The right time and the right place are not here

No place of grace for those who avoid the face

No time to rejoice for those who walk among noise and deny

the voice

Will the veiled sister pray for

Those who walk in darkness, who chose thee and oppose thee,

Those who are torn on the horn between season and season,

time and time, between

Hour and hour, word and word, power and power, those who wait

In darkness? Will the veiled sister pray

For children at the gate

Who will not go away and cannot pray:

Pray for those who chose and oppose

O my people, what have I done unto thee.

Will the veiled sister between the slender

Yew trees pray for those who offend her

And are terrified and cannot surrender

And affirm before the world and deny between the rocks

In the last desert before the last blue rocks

The desert in the garden the garden in the desert

Of drouth, spitting from the mouth the withered apple-seed.

O my people.

VI

Although I do not hope to turn again

Although I do not hope

Although I do not hope to turn

Wavering between the profit and the loss

In this brief transit where the dreams cross

The dreamcrossed twilight between birth and dying

(Bless me father) though I do not wish to wish these things

From the wide window towards the granite shore

The white sails still fly seaward, seaward flying

Unbroken wings

And the lost heart stiffens and rejoices

In the lost lilac and the lost sea voices

And the weak spirit quickens to rebel

For the bent golden-rod and the lost sea smell

Quickens to recover

The cry of quail and the whirling plover

And the blind eye creates

The empty forms between the ivory gates

And smell renews the salt savour of the sandy earth

This is the time of tension between dying and birth

The place of solitude where three dreams cross

Between blue rocks

But when the voices shaken from the yew-tree drift away

Let the other yew be shaken and reply.

Blessèd sister, holy mother, spirit of the fountain, spirit

of the garden,

Suffer us not to mock ourselves with falsehood

Teach us to care and not to care

Teach us to sit still

Even among these rocks,

Our peace in His will

And even among these rocks

Sister, mother

And spirit of the river, spirit of the sea,

Suffer me not to be separated

And let my cry come unto Thee.

***************************************************************************

The numbers say it all: Canada is a climate-change miscreant, Jeffrey Simpson, June 3 2010.

The annual report required by all signatories to the original Kyoto Protocol is depressing

When the Harper government has something it wants everybody to know, it sends the Prime Minister to make an “announcement,” gathers a gaggle of ministers to nod their heads at the words of their sage boss, issues press releases and, if necessary, buys newspaper and television advertising to trumpet itself.

When, however, the news is bad, well, standard procedure is either not to release the information at all, or to post it on a website without telling anyone, hoping the news will pass unnoticed.

Such was the case this week when quietly, of course, Environment Canada posted on its website the embarrassing news about the government’s expensive and largely futile measures to combat greenhouse gas emissions.

Try as it might, the government could not put lipstick on a pig. The numbers were there, stark and depressing, in an annual report required by all signatories to the original Kyoto Protocol. The bottom line: The world is right to consider Canada a climate-change miscreant.

On Canadian soil, two world leaders have recently urged Canada to do more. Mexican President Felipe Calderon and United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon both made that pitch, implicitly criticizing Canada’s bad record. Their critiques are rooted in recent history, stretching back to the Liberal governments of Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin. The critiques remain valid today, which is why Canada has no credibility whatsoever internationally on the climate-change file.

According to the government’s own numbers, actual emissions will grow in absolute terms in every year from 2009 to 2012. All the government’s many and expensive policies will have done is to slow the increase, and then only slightly – by 10 million tonnes in 2012, against countrywide emissions of more than 700 million tonnes. At this rate, Canada will not achieve even the Harper government’s modest reduction target: a 17-per-cent drop in absolute reductions by 2020 based on 2005 emissions, a softer target than the 20-per-cent drop the government had previously promised.

The numbers show how useless and expensive are some of the government’s policies. For example, Ottawa is going to throw $1.5-billion into biofuels, largely ethanol, over the next nine years without a significant decline in emissions, because, as is obvious, the biofuels program is an agricultural subsidy program rather than a serious measure against emissions.

Or how about the absurdity of the transit tax credit, announced in an election campaign as a climate-change-fighting program? That all-politics-all-the-time program is estimated to reduce emissions by just over a risible 3,000 tonnes. And then comes the big Clean Energy Fund and Clean Air and Climate Change Trust Fund, together worth $2.5-billion, which the government admits “are not expected to result in quantifiable reductions by 2012.”

Maybe these funds will produce some reductions later, but then that would be entirely in keeping with the Harper government’s leisurely approach to climate change, an approach best summed up in the document’s statement that the government focuses on “long-term results.” As students of governments know, when they say everything is focused on “long-term results,” it usually means the government in question is not serious.

Yes, climate change is a long-term challenge, but the longer the inaction, the worse the challenge becomes. The further Canada falls behind other countries whose governments are more committed to replacing fossil fuels. When the government boasts that Canada is becoming a “global leader in the development of clean technologies and clean energy alternatives,” the assertion is belied by facts, such as Canada’s relatively small share of stimulus monies spent on such technologies.

Canada’s record is so poor due (among other reasons) to the unwillingness to put a price on carbon emissions (except in B.C. through a carbon tax, and Alberta through a middling emissions-intensity tax). Having ruled out a carbon tax, the Harper government has tied Canada to the U.S. policy, including the creation of a cap-and-trade system.

Cap-and-trade is almost certainly dead in the U.S. Congress. By essentially forgoing any willingness to act as a sovereign country, and putting Canadian policy instead into the uncertain hands of American legislators who are unable to agree on just about anything, Canada’s overall emissions record is likely to be an international embarrassment, further witness to which is contained in this week’s figures.

***************************************************************************

Emissions reductions 10 times less than government’s projections: report, Gloria Galloway, June 3 2010.

Critics say results show Harper government failing to reduce Canada’s greenhouse gas pollution

Environment Canada overestimated by 10 times the amount of emissions reductions that result from government measures when it reported last year on its efforts to meet this country’s obligations under the Kyoto protocol.

What is more, although Ottawa started handing over the first installments of a five-year $1.5-billion Clean Air and Climate Change Trust fund to the provinces in 2008, the federal government cannot monitor them or verify whether they are being spent for the intended purpose.

Those findings are in the fourth instalment of an annual report on the Kyoto Protocol that Environment Canada completed last month.

“When you compare this year’s plan and last year’s plan, you see, as recently as last year, the government was exaggerating tenfold the emissions reductions that would be achieved by its policies in 2010,” Matthew Bramley, the director of climate change for the Pembina Institute, said in an interview on Thursday.

“It really is an admission on the part of the federal government that it is neither implementing nor currently planning to implement any policies to substantially reduce Canada’s greenhouse gas pollution.”

The report called the Climate Change Plan for the Purposes of the Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act is a requirement of a Liberal private-member’s bill that was passed despite Conservative objections in 2007.

Unlike other environment publications, the new report is not readily available on the federal department’s website. Instead, anyone looking for it must click on a link, then click on a second link, enter an e-mail address and wait for it to be forwarded.

The 2009 report projected that government measures would reduce carbon emissions in 2010 by 52 megatonnes. But the 2010 report projects this year’s decrease to be just five megatonnes.

The government also admits for the first time in the 2010 report that the federal Environment Commissioner was right when he said last year that Ottawa may never know whether the large sums of money being handed to the provinces to fight climate change are being spent for that purpose.

And this year’s report says that the $1-billion over five years that the government promised last year to spend as part of its Green Infrastructure Fund is “not expected to result in quantifiable reductions [in emissions] by 2012.”

When Environment Minister Jim Prentice was asked for his opinion about the new report, his spokesman, Frederic Baril, said in an e-mail: “While there is still work to be done, improvements in our emissions levels strengthen this government's commitment to continue tackling climate change and reduce Canada's greenhouse gas.”

In its 2007 Turning the Corner plan for greenhouse-gas reduction, the government promised to set targets for big industry by this year. That has not happened, and Mr. Prentice has said Canada will instead release its regulations on carbon emissions on a timetable that matches that of the United States.

Linda Duncan, the environment critic for the NDP, said the new report shows that “not only are they backsliding on the minimal commitments in Turning the Corner, they have now scaled back by a factor of 10 from what they said they’d do last year.”

***************************************************************************

The Shadow over Israel, Margaret Atwood, June 2 2010.

Until Palestine has its own 'legitimized' state within its internationally recognized borders, the Shadow will remain.

The Moment

The moment when, after many years

of hard work and a long voyage,

you stand in the centre of your room,

house, half-acre, square mile, island, country,

knowing at last how you got there,

and say, I own this,

is the same moment the trees unloose

their soft arms from around you,

the birds take back their language,

the cliffs fissure and collapse,

the air moves back from you like a wave

and you can’t breathe.

No, they whisper. You own nothing.

You were a visitor, time after time

Climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming.

We never belonged to you.

You never found us.

It was always the other way round.

Recently I was in Israel. The Israelis I met could not have been more welcoming. I saw many impressive accomplishments and creative projects, and talked with many different people. The sun was shining, the waves waving, the flowers were in bloom. Tourists jogged along the beach at Tel Aviv as if everything was normal.

But… there was the Shadow. Why was everything trembling a little, like a mirage? Was it like that moment before a tsunami when the birds fly to the treetops and the animals head for the hills because they can feel it coming?

“Every morning I wake up in fear,” someone told me. “That’s just self-pity, to excuse what’s happening,” said someone else. Of course, fear and self-pity can both be real. But by “what’s happening,” they meant the Shadow.

I’d been told ahead of time that Israelis would try to cover up the Shadow, but instead they talked about it non-stop. Two minutes into any conversation, the Shadow would appear. It’s not called the Shadow, it’s called “the situation.” It haunts everything.

The Shadow is not the Palestinians. The Shadow is Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, linked with Israeli’s own fears. The worse the Palestinians are treated in the name of those fears, the bigger the Shadow grows, and then the fears grow with them; and the justifications for the treatment multiply.

The attempts to shut down criticism are ominous, as is the language being used. Once you start calling other people by vermin names such as “vipers,” you imply their extermination. To name just one example, such labels were applied wholesale to the Tutsis months before the Rwanda massacre began. Studies have shown that ordinary people can be led to commit horrors if told they’ll be acting in self-defense, for “victory,” or to benefit mankind.

I’d never been to Israel before, except in the airport. Like a lot of people on the sidelines – not Jewish, not Israeli, not Palestinian, not Muslim – I hadn’t followed the “the situation” closely, though, also like most, I’d deplored the violence and wished for a happy ending for all.

Again like most, I’d avoided conversations on this subject because they swiftly became screaming matches. (Why was that? Faced with two undesirable choices, the brain – we’re told -- chooses one as less evil, pronounces it good, and demonizes the other.)

I did have some distant background. As “Egypt” at a Model U.N. in 1956, my high school’s delegation had presented the Palestinian case. Why was it fair that the Palestinians, innocent bystanders during the Holocaust, had lost their homes? To which the Model Israel replied, “You don’t want Israel to exist.” A mere decade after the Camps and the six million obliterated, such a statement was a talk-stopper.

Then I’d been hired to start a Nature program at a liberal Jewish summer camp. The people were smart, funny, inventive, idealistic. We went in a lot for World Peace and the Brotherhood of Man. I couldn’t fit this together with the Model U.N. Palestinian experience. Did these two realities nullify each other? Surely not, and surely the humane Jewish Brotherhood-of-Manners numerous in both the summer camp and in Israel itself would soon sort this conflict out in a fair way.

But they didn’t. And they haven’t. And it’s no longer 1956. The conversation has changed dramatically. I was recently attacked for accepting a cultural prize that such others as Atom Egoyan, Al Gore, Tom Stoppard, Goenawan Mohamad, and Yo-Yo Ma had previously received. This prize was decided upon, not by an instrument of Israeli state power as some would have it, but by a moderate committee within an independent foundation. This group was pitching real democracy, open dialogue, a two-state solution, and reconciliation. Nevertheless, I’ve now heard every possible negative thing about Israel – in effect, I’ve had an abrupt and searing immersion course in present-day politics. The whole experience was like learning about cooking by being thrown into the soup pot.

The most virulent language was truly anti-Semitic (as opposed to the label often used to deflect criticism). There were hot debates among activists about whether boycotting Israel would “work,” or not; about a one-state or else a two-state solution; about whether a boycott should exclude culture, as it is a bridge, or was that hypocritical dreaming? Was the term “apartheid” appropriate, or just a distraction? What about “de-legitimizing” the State of Israel? Over the decades, the debate had acquired a vocabulary and a set of rituals that those who hadn’t hung around universities – as I had not -- would simply not grasp.

Some kindly souls, maddened by frustration and injustice, began by screaming at me; but then, deciding I suppose that I was like a toddler who’d wandered into traffic, became very helpful. Others dismissed my citing of International PEN and its cultural-boycott-precluding efforts to free imprisoned writers as irrelevant twaddle. (An opinion cheered by every repressive government, extremist religion, and hard-line political group on the planet, which is why so many fiction writers are banned, jailed, exiled, and shot.)

None of this changes the core nature of the reality, which is that the concept of Israel as a humane and democratic state is in serious trouble. Once a country starts refusing entry to the likes of Noam Chomsky, shutting down the rights of its citizens to use words like “Nakba,” and labelling as “anti-Israel” anyone who tries to tell them what they need to know, a police-state clampdown looms. Will it be a betrayal of age-old humane Jewish traditions and the rule of just law, or a turn towards reconciliation and a truly open society?

Time is running out. Opinion in Israel may be hardening, but in the United States things are moving in the opposite direction. Campus activity is increasing; many young Jewish Americans don’t want Israel speaking for them. America, snarled in two chaotic wars and facing increasing international anger over Palestine, may well be starting to see Israel not as an asset but as a liability.

Then there are people like me. Having been preoccupied of late with mass extinctions and environmental disasters, and thus having strayed into the Middle-eastern neighbourhood with a mind as open as it could be without being totally vacant, I’ve come out altered. Child-killing in Gaza? Killing aid-bringers on ships in international waters? Civilians malnourished thanks to the blockade? Forbidding writing paper? Forbidding pizza? How petty and vindictive! Is pizza is a tool of terrorists? Would most Canadians agree? And am I a tool of terrorists for saying this? I think not.

There are many groups in which Israelis and Palestinians work together on issues of common interest, and these show what a positive future might hold; but until the structural problem is fixed and Palestine has its own “legitimized” state within its internationally recognized borders, the Shadow will remain.

“We know what we have to do, to fix it,” said many Israelis. “We need to get beyond Us and Them, to We,” said a Palestinian. This is the hopeful path. For Israelis and Palestinians both, the region itself is what’s now being threatened, as the globe heats up and water vanishes. Two traumas create neither erasure nor invalidation: both are real. And a catastrophe for one would also be a catastrophe for the other.

***************************************************************************

Gaza flotilla drives Israel into a sea of stupidity, Gideon Levy, May 30 2010.

Of course the peace flotilla will not bring peace, and it won't even manage to reach the Gaza shore. The action plan has included dragging the ships to Ashdod port, but it has again dragged us to the shores of stupidity and wrongdoing

The Israeli propaganda machine has reached new highs its hopeless frenzy. It has distributed menus from Gaza restaurants, along with false information. It embarrassed itself by entering a futile public relations battle, which it might have been better off never starting. They want to maintain the ineffective, illegal and unethical siege on Gaza and not let the "peace flotilla" dock off the Gaza coast? There is nothing to explain, certainly not to a world that will never buy the web of explanations, lies and tactics.

Only in Israel do people still accept these tainted goods. Reminiscent of a pre-battle ritual from ancient times, the chorus cheered without asking questions. White uniformed soldiers got ready in our name. Spokesmen delivered their deceptive explanations in our name. The grotesque scene is at our expense. And virtually none of us have disturbed the performance.

The chorus has been singing songs of falsehood and lies. We are all in the chorus saying there is no humanitarian crisis in Gaza. We are all part of the chorus claiming the occupation of Gaza has ended, and that the flotilla is a violent attack on Israeli sovereignty - the cement is for building bunkers and the convoy is being funded by the Turkish Muslim Brotherhood. The Israeli siege of Gaza will topple Hamas and free Gilad Shalit. Foreign Ministry spokesman Yossi Levy, one of the most ridiculous of the propagandists, outdid himself when he unblinkingly proclaimed that the aid convoy headed toward Gaza was a violation of international law. Right. Exactly.

It's not the siege that is illegal, but rather the flotilla. It wasn't enough to distribute menus from Gaza restaurants through the Prime Minister's Office, (including the highly recommended beef Stroganoff and cream of spinach soup ) and flaunt the quantities of fuel that the Israeli army spokesman says Israel is shipping in. The propaganda operation has tried to sell us and the world the idea that the occupation of Gaza is over, but in any case, Israel has legal authority to bar humanitarian aid. All one pack of lies.

Only one voice spoiled the illusory celebration a little: an Amnesty International report on the situation in Gaza. Four out of five Gaza residents need humanitarian assistance. Hundreds are waiting to the point of embarrassment to be allowed out for medical treatment, and 28 already have died. This is despite all the Israeli army spokesman's briefings on the absence of a siege and the presence of assistance, but who cares?

And the preparations for the operation are also reminiscent of a particularly amusing farce: the feverish debate among the septet of ministers; the deployment of the Masada unit, the prison service's commando unit that specializes in penetrating prison cells; naval commando fighters with backup from the special police anti-terror unit and the army's Oketz canine unit; a special detention facility set up at the Ashdod port; and the electronic shield that was supposed to block broadcast of the ship's capture and the detention of those on board.

And all of this in the face of what? A few hundred international activists, mostly people of conscience whose reputation Israeli propaganda has sought to besmirch. They are really mostly people who care, which is their right and obligation, even if the siege doesn't concern us at all. Yes, this flotilla is indeed a political provocation, and what is protest action if not political provocation?