I started all this nonsense in September 2005 when I found myself in a well-paying job with a computer and nothing to do all day, if there had been anything to do it would have required access to the Internet so ... there I was, perfectly poised, a Brasilian colleague mentioned blogging, another, a few cubicles away had a blog going ... and it was done like dinner! Bob's 1965 editorial on wasted words notwithstanding

and as the years have gone by I have spent more and more time at it, an addict maybe? I don't think it is addiction really, just nothing else to do ... that and watching a tree:

so ... this is what I see when I look out of my window ...

I have actually been watching this particular tree (shades of Antoine de Saint Exupéry and Le Petit Prince / The Little Prince tending baobab trees & roses, & befriending foxes with his apprivoiser :-) since January when I moved in here, at first it seemed that there were two trees side-by-side, a sort of Priamus & Thisbe with the space between them elegantly arched, whorled - but on investigation it turned out to be one tree with two trunks separating about 25 feet up

inertia being what it is I didn't move on the idea until June, the camera is an Olympus Stylus 1010 which is obviously too complicated for me since I cannot even get the auto-focus to work, if you are offered one - just say 'no', I have posted it previously twice, on June 5th & June 21st,

there was a dramatic storm in August and I thought of trying to capture the tossing twisting branches in a video, but the camera and I were not up to it, nor have I found out what species it is, I have not gone and collected a leaf or two from the sidewalk next to it ... some kind of maple I imagine but I don't even know if that is reasonable

a-and the antecedents grow more-and-more oblique, the illustration for Rudyard Kipling's The Cat Who Walked By Himself, and two phrases from two verses of Bob Dylan's Dirge ...

Este é o desenho do Gato que Andava Sozinho, a andar com a sua selvagem solidão pelos Bosques Humidos e Selvagens e a dar com a sua cauda selvagem. Não há mais nada no desenho, excepto alguns cogumelos venenosos. Tinham de crescer all, porque os bosques eram tão humidos. A coisa papuda no ramo mais baixo nao é um passaro. É musgo que cresceu ali, porque os Bosques Selvagens eram tão húmidos.

Este é o desenho do Gato que Andava Sozinho, a andar com a sua selvagem solidão pelos Bosques Humidos e Selvagens e a dar com a sua cauda selvagem. Não há mais nada no desenho, excepto alguns cogumelos venenosos. Tinham de crescer all, porque os bosques eram tão humidos. A coisa papuda no ramo mais baixo nao é um passaro. É musgo que cresceu ali, porque os Bosques Selvagens eram tão húmidos.Por baixo do desenho verdadeiro está um desenho da Caverna acolhedora para que o Homem e a Mulher foram depois de vir o Bebé. Era a sua Caverna de Verao, e plantaram trigo em frente dela. O Homem está a andar no Cavalo para encontrar a Vaca para a trazer de volta à Caverna para ser mungida. Tem a mão levantada para chamar o Cão, que nadou para o outro lado do rio, à procura de coelhos.

Heard your songs of freedom and man forever stripped,

Acting out his folly while his back is being whipped.

Like a slave in orbit, he's beaten 'til he's tame,

All for a moment's glory and it's a dirty, rotten shame.

So sing your praise of progress and of the doom machine,

The naked truth is still taboo whenever it can be seen.

Lady Luck, who shines on me, will tell you where I'm at,

I hate myself for lovin' you, but I should get over that.

hope springs eternal ... just exactly two weeks ago, on Friday October 23, we had Barack Obama Challenging Americans to Lead the Global Economy in Clean Energy, and pointing at the 'cynical deniers', and today Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd excoriating them in a speech to the Lowy Institute for International Policy in Sydney,

I grew up on Walt Disney, we got our first TV set sometime in the early 50s and his program was almost never missed, and more than ten years later I was still watching it, he died in 1966, about the time that Disney World opened in Florida, I guess I was too old for it by then and I never understood DisneyLand's attraction, and I remember that the show continuing after his death was a question for me too, naive innocent child that I was ... I didn't know then that he had been one of Senator Joseph McCarthy's star boys, and it was much later on that I finally had a clue from Simon & Garfunkel:

I grew up on Walt Disney, we got our first TV set sometime in the early 50s and his program was almost never missed, and more than ten years later I was still watching it, he died in 1966, about the time that Disney World opened in Florida, I guess I was too old for it by then and I never understood DisneyLand's attraction, and I remember that the show continuing after his death was a question for me too, naive innocent child that I was ... I didn't know then that he had been one of Senator Joseph McCarthy's star boys, and it was much later on that I finally had a clue from Simon & Garfunkel:Kodachrome, give us those nice bright colours

Give us the greens of summers

Make you think all the world's a sunny day, oh yeah

I got a Nikon camera, I love to take a photographs

Oh mama don't take my Kodachrome away.

by the time I was reading stories to my children anything that showed up with the Disney logo was soon tossed in the bin, no ideology involved just didn't like it, and there were other stories that we did like: The Butterfly That Stamped & Everyone Knows What a Dragon Looks Like & The Snow Queen f'rinstance, to mention but a few

by the time I was reading stories to my children anything that showed up with the Disney logo was soon tossed in the bin, no ideology involved just didn't like it, and there were other stories that we did like: The Butterfly That Stamped & Everyone Knows What a Dragon Looks Like & The Snow Queen f'rinstance, to mention but a fewif I had to take Disney's (essentially daemonic) image and turn it inside out, transform it into something fit to splice into a fecund myth - well, it would be this image of Gaudi's Sagrada Familia in the dawn with a Greenpeace banner flying from it :-)

round again to Frye's, "that these imbecile words are euphemisms for manic-depressive highs and lows, and that anyone who struggles for sanity avoids both," a-and maybe threading the Walt Disney needle was just shit-house luck (if this is sanity that is :-)

Abang Othow, also connected with Australia, has co-written a book, The long road to safety: Abang Othow's story with Elizabeth Corfe & Timothy Ide, aimed at youngsters, comparable to Kagiso Lesego Molope's The Mending Season, mentioned below, in that regard maybe - if I could ever get a copy of either one maybe I could see more clearly!

part of it is available at Google Books, and with a few more pictures:

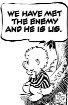

Charles Schulz disliked the Pig-Pen character apparently.

Charles Schulz disliked the Pig-Pen character apparently.

For Major Major, it meant the end of the game. His face flushed with discomfort, and he was rooted to the spot in disbelief as the rain clouds gathered above him again.

For Major Major, it meant the end of the game. His face flushed with discomfort, and he was rooted to the spot in disbelief as the rain clouds gathered above him again.Joseph Heller, Catch-22.

one of Major Major's shortcomings was undoubtedly that he told the truth when asked, as Bob says, "the naked truth is still taboo wherever it can be seen," and I guess some people have learned and some like myself are still learning just how this works itself out on the ground, there is a connection with 'stream of consciousness' in literature as it was presented to us in the 60s via James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and later for a few there was Finnegan's Wake, but I never considered until just now that the words as they arrived on the page were anything but spontaneous, a necessary disconnect that we were not told about :-)

and mixed together with imprecise notions of Blake's 'Christian forbearance' ... maybe that was how it became such a toxic psychological stew ...

and too, there is the element of time, lag-time, inertia, social change takes generations to accomplish and that is a good thing probably since it comprises events which happen in the dark uncharted zones, where reason holds no sway and chaos reigns ...

Sid Ryan and his cronies in The United Church of k-k-Canada teamed up a while ago on their embargo of Israel, imperfect comparisons with South Africa's apartheid no doubt contributing to their nonsense, I have posted here on the subject before but I can't be bothered just now summarizing ... and anyway the issue is so complex and complicated, threads like the Goldstone Report from the so called United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) which just lead everywhere, but in my simple brain the discovery of the Francop fiasco (or should it be 'imbroglio'?), a German boat registered in Antigua and carrying arms from Iran to Syria, destined for Hezbollah/Hizbollah in Lebanon, well, in my simple brain this simplifies the thing somewhat ... will the UCC nitwits eventually rationalize the Francop into their warped ideological fabric? stupid question ...

Sid Ryan and his cronies in The United Church of k-k-Canada teamed up a while ago on their embargo of Israel, imperfect comparisons with South Africa's apartheid no doubt contributing to their nonsense, I have posted here on the subject before but I can't be bothered just now summarizing ... and anyway the issue is so complex and complicated, threads like the Goldstone Report from the so called United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) which just lead everywhere, but in my simple brain the discovery of the Francop fiasco (or should it be 'imbroglio'?), a German boat registered in Antigua and carrying arms from Iran to Syria, destined for Hezbollah/Hizbollah in Lebanon, well, in my simple brain this simplifies the thing somewhat ... will the UCC nitwits eventually rationalize the Francop into their warped ideological fabric? stupid question ...but there is a personal angle here too - looking for some society I went along to a meeting of Maude Barlow's Council of Canadians a few months ago, knowing beforehand that she is tight with Sid Ryan but hoping against hope that it was not that tight maybe, and discovered a Brit who went terrier-rabid at any disrespect to 'our friend Sid' ... oh my ... and again, looking for someplace to worship, met a gent from Bathurst United, which turns out to be the nexus or plexus or whatever you want to call it of the UCC adherents to the gospel according to Sid Ryan ... so yeah, I do identify to a degree with Joe Btfsplk & Pig-Pen & Major Major Major Major

and I guess this blogging nonsense at least helps to pass the time ...

I notice that Greenpeace have discovered 'who is to blame' - it is the United States natch, so they dress up a statue of Christopher Columbus in Barcelona, staple twenty pounds of headlines to its chest and carry on ... I was talking to my daughter on the phone the other day and mentioned that I was more-or-less supporting Greenpeace since they seemed to be just about the only ones doing anything, she groaned ...

I notice that Greenpeace have discovered 'who is to blame' - it is the United States natch, so they dress up a statue of Christopher Columbus in Barcelona, staple twenty pounds of headlines to its chest and carry on ... I was talking to my daughter on the phone the other day and mentioned that I was more-or-less supporting Greenpeace since they seemed to be just about the only ones doing anything, she groaned ... I groan too, when I hear their local chief-ette, Kim Fry (?) speaking at Queen's Park on the 24th of October and she goes on bragging about getting arrested, counting the number of arrests, itemizing & detailing the arrests, cutting notches like some TV gunslinger ... not that getting arrested is a bad thing, or even undesirable, just that it is not the point is it? not the be-all and end-all, not the objective of the action eh? and now this 'the US is to blame' bullshit ... what ever happened to Pogo consciousness? or maybe this is all just a play on words? is that it?

I groan too, when I hear their local chief-ette, Kim Fry (?) speaking at Queen's Park on the 24th of October and she goes on bragging about getting arrested, counting the number of arrests, itemizing & detailing the arrests, cutting notches like some TV gunslinger ... not that getting arrested is a bad thing, or even undesirable, just that it is not the point is it? not the be-all and end-all, not the objective of the action eh? and now this 'the US is to blame' bullshit ... what ever happened to Pogo consciousness? or maybe this is all just a play on words? is that it?or "be a nice fellow?" as I descend into a kind of continual groaning Tourette's (which they say is inherited) comprising mostly "Fucking Bitch! Cunt! Fucking Shit! Useless! You are Useless! Good for Fucking Nothing!" which is maybe not that healthy ... or maybe it is? this from someone who really does not understand even the differences between bathos: in rhetoric, a ludicrous descent from the elevated to the commonplace in writing or speech, anticlimax, and pathos: that quality in speech, writing, music, or artistic representation (or transferred sense in events, circumstances, persons, etc.) which excites a feeling of pity or sadness, the power of stirring tender or melancholy emotion, and pathetic fallacy: the attribution of human response or emotion to inanimate nature,

"put him in a prison cell, but one time he could-a been the champion of the world."

thinking of Major Major Major Major, amd now, getting along, Milo the Mayor where the dominant quality is selfishness, makes me angry ... keeping in mind that I have read this Catch-22 a number of times before and I know how it ends, which ending never satisfied me

anger? aha! and up pops Paul Krugman, saying Paranoia Strikes Deep, quoting Buffalo Springfield, and referring to Richard Hofstadter on The Paranoid Style in American Politics from waaaaay back in 1964

anger, it was a virtue to us in the 60s, there was a film The Last Angry Man, net tells me it was in 1959 ... don't remember seeing it but it was a presence somehow ... (first movie I ever saw was Phantom from Space in 1953 which frightened me so badly that I made my father take me out of the theatre, he was chuffed, I think it was a long time before I saw another ... maybe it was the late 50s then when we finally got our TV (?))

so ... it has taken a long time for me to even begin to understand why anger is one of the seven deadly sins ... anger & paranoia are linked ... this is sketchy ... also Frye's comment on Pynchon's creative use of paranoia ... very sketchy indeed ...

walked past the tree this morning, some kind of alder (?), 'deltoid' leaves ... there is another name which is on the tip of my tongue ...

Appendices:

1. Prime Minister Address to the Lowy Institute, Kevin Rudd, 6 Nov. 2009.

1a. Kevin Rudd on Slow TV.

2-1. Catch-22, nine. MAJOR MAJOR MAJOR MAJOR.

2-2. Catch-22, twenty-two. MILO THE MAYOR.

3. Israelis 'seize Iran arms ship', BBC, 4 Nov. 2009.

4-1. Paranoia Strikes Deep, Paul Krugman, Nov. 9 2009.

4-2. The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Richard Hofstadter, 1964.

***************************************************************************

Prime Minister Address to the Lowy Institute, Kevin Rudd, 6 Nov. 2009.

I acknowledge the First Australians on whose land we meet, and whose cultures we celebrate as among the oldest continuing cultures in human history.

Thank you Michael and thanks to all the supporters of the Lowy Institute for joining us today.

As you know, I attended the Major Economies Forum in L'Aquila in July; I was recently at the G20 Leaders meeting in Pittsburgh; and next week I will travel to the APEC Leaders meeting in Singapore.

At each of these meetings, and in constant bilateral conversations being conducted by national leaders around the world, the common thematic is: What does our nation, what does our region and what does the world do to respond to climate change, the greatest long term threat to us all?

As APEC leaders gather in Singapore next week, this is a critical question.

The Asia Pacific region will play the key role in leading the world into economic recovery. Similarly, our region must play a central role if we are to forge a global consensus on tackling climate change.

This afternoon I want to set out the views that I will be reflecting to other world leaders in the days and weeks ahead, in bilateral conversations and in forums such as APEC, leading up to the Copenhagen summit.

Australia and the world today stand at critical junctures in our national and global strategies to tackle climate change.

It is around 20 days until the Senate votes on the Australian Government's Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme.

20 days until the most important vote on our national strategy to tackle climate change.

20 days away from the vote on the Government's cap and trade emissions trading system which both sides of politics have recognised as the lowest cost way to tackle climate change.

And we are just 31 days away from the Copenhagen Conference of Parties - an historic moment to forge a global deal to put a global price on carbon.

Today we are approaching the crossroads. Both these policies are reaching crunch time.

When you strip away all the political rhetoric, all the political excuses, there are two stark choices - action or inaction. The resolve of the Australian Government is clear - we choose action, and we do so because Australia's fundamental economic and environmental interests lie in action.

Action now. Not action delayed.

As one of the hottest and driest continents on earth, Australia's environment and economy will be among the hardest and fastest hit by climate change if we do not act now. The scientific evidence from the CSIRO and other expert bodies have outlined the implications for Australia, in the absence of national and global action on climate change:

* Temperatures in Australia rising by around five degrees by the end of the century.The Government took a plan to tackle climate change to the last election, to tackle the risks climate change poses to our planet, and especially to the health, lifestyle and livelihoods of our children.

* By 2070, up to 40 per cent more drought months are projected in eastern Australia and up to 80 per cent more in south-western Australia.

* A fall in irrigated agricultural production in the Murray Darling Basin of over 90 per cent by 2100.

* Storm surges and rising sea levels - putting at risk over 700,000 homes and businesses around our coastlines, with insurance companies warning that preliminary estimates of the value of property in Australia exposed to the risk of land being inundated or eroded by rising sea levels range from $50 billion to $150 billion.

* Our Gross National Product dropping by nearly two and a half per cent through the course of this century from the devastation climate change would wreak on our infrastructure alone.

That plan included two fundamental parts:

* First, a domestic plan of action to reduce Australia's carbon pollution, including:This was the platform we took to the Australian people at the election. This is the program of action we have been prosecuting over the past two years. Yet the cornerstone of this program of action, the CPRS, still lies stymied in the Senate.o Expanding the Renewable Energy Target to 20 per cent by 2020 (and subsequently directly investing over $2 billion in renewable energy, including investment in large scale solar generating capacity that will be three times larger than the world's current largest project).* The second part of our strategy is participation in global action to tackle climate change, including:

o A national energy efficiency strategy to reduce the energy that we can consume, and undertaking the largest investment in energy efficiency ever seen in this country.

o A Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme that will increase the cost of carbon over time and facilitate a transition to a low carbon pollution economy.o ratifying the Kyoto Protocol;

o participating in global technology transfers - including Australian leadership in a global coalition to develop carbon capture and storage through the Australia-initiated Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute; and

o strong engagement towards a new post-Kyoto global agreement.

Australia has certainly not been alone in our endeavours to tackle global climate change. At the same time, around the world we have seen nations of every political stripe take concrete action to work towards legislation in this critical area - actions which have been slowly building towards coordinated international action to tackle climate change. And most nations have been engaged in the multilateral process - through the Bali Roadmap two years ago, through the 14th Conference of the Parties in Poznan, Poland last year, and the intensifying global negotiations leading up to the 15th Conference of Parties in Copenhagen this year.

Today, the culmination of this domestic and global action is in sight. Much progress has been made, but, the truth is that there is still a long way to go. In fact, the hardest part of our journey is ahead of us over the next 31 days.

This is a profoundly important time for our nation, for our world and for our planet.

In Australia, we must pass our Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme - to deliver certainty for business at home and to play our part abroad in any global agreement to bring greenhouse gases down.

President Obama in the United States is also working hard so that he can take strong commitments to Copenhagen. And let us never forget that in the US, as in Australia, under both our respective previous governments, zero action was taken on bringing in cap and trade schemes meaning that the governments that replaced them began with a zero start.

Other countries are striving to build domestic political momentum in their own countries to take strong commitments into the global deal.

The challenge we face, and others around the world face, is to build momentum and overcome domestic political constraints.

The truth is this is hard, because the climate change skeptics, the climate change deniers, the opponents of climate change action are active in every country.

They are a minority. They are powerful. And invariably they are driven by vested interests.

Powerful enough to so far block domestic legislation in Australia, powerful enough to so far slow down the passage of legislation through the US Congress. And ultimately - by limiting the ambition of national climate change commitments - they are powerful enough to threaten a deal on global climate change both in Copenhagen and beyond.

The opponents of action on climate change fall into one of three categories:

* First, the climate science deniers.Together, these groups, alive in every major country including Australia, constitute a powerful global force for inaction, and they are particularly entrenched in a range of conservative parties around the world.

* Second, those that pay lip service to the science and the need to act on climate change but oppose every practicable mechanism being proposed to bring about that action.

* Third, those in each country that believe their country should wait for others to act first.

As we approach Copenhagen, these three groups of climate skeptics are quite literally holding the world to ransom, provoking fear campaigns in every country they can, blocking or delaying domestic legislation in every country they can, with the objective of slowing and if possible destroying the momentum towards a global deal on climate change.

As we approach the Copenhagen conference these groups of climate change deniers face a moment of truth, and the truth is this: we will need to work much harder to reach an agreement in Copenhagen because these advocates of inaction are holding back domestic commitments, and are in turn holding back global commitments on climate change.

It is time to be totally blunt about the agenda of the climate change skeptics in all their colours - some more sophisticated than others.

It is to destroy the CPRS at home, and it is to destroy agreed global action on climate change abroad, and our children's fate - and our grandchildren's fate - will lie entirely with them.

It's time to remove any polite veneer from this debate. The stakes are that high.

The first category of those opposed to action is the vocal group of conservatives who do not accept the scientific consensus. This group believes the science is inconclusive and does not provide an evidentiary basis for anthropogenic climate change.

In Australia, before the 2007 election, this group was thought to be relatively small. There appeared - for a time - to be bipartisan consensus on the need for action on climate change. In recent times, this bipartisan support has frayed.

As one Liberal Member of Parliament said to Phil Coorey of the Sydney Morning Herald last year: "[at the last election we supported an ETS because] we were staring at an electoral abyss. We had to pretend we cared." (SMH, 28 JULY 2008)

More recently that pretence has been increasingly cast aside. Would-be Liberal leader Tony Abbott said in July this year that "the science ... is contentious to say the least". (27 July 2009)

Liberal Senator Cory Bernardi said: "I remain unconvinced about the need for an ETS given that carbon dioxide is vital for life on earth".

Liberal Senator Alan Eggleston said: "Levels of carbon dioxide have risen in the world, but whether or not this is the sole cause or just a contributor to climate change is, I think, unanswered." (11 AUGUST 2009)

Liberal Senate leader Nick Minchin said this year: "CO2 is not by any stretch of the imagination a pollutant... This whole extraordinary scheme is based on the as yet unproven assertion that anthropogenic emissions of CO2 are the main driver of global warming." (11 AUGUST 2009)

Alternative Liberal leader Joe Hockey - who knows better - has been drawn into the same sort of doublespeak, remarking on the Today Show in August: "Look, climate change is real Karl, you know whether it is made by human beings or not that is open to dispute." (12 AUGUST 2009)

Even the leader of the Opposition, once Minister for the Environment, Malcolm Turnbull, has flirted with this doublespeak, telling Alan Jones on 2GB: "I think most people have at least some doubts about the science." (19 JUNE 2009)

The tentacles of the climate change skeptics reach deep into the ranks of the Liberal Party, and once you add the National Party it's plan the skeptics and the deniers are a major force.

Climate sceptics are also a powerful political lobby in the United States.

Republican National Committee Chairman Michael Steel said on 6 March 2009: "We are cooling. We are not warming. The warming you see out there, the supposed warming, and I am using my finger quotation marks here, is part of the cooling process."

House Minority Leader John Boehner said on April 19 2009: "The idea that carbon dioxide is a carcinogen that is harmful to our environment is almost comical. Every time we exhale, we exhale carbon dioxide."

Republican Congressman John Shimkus said on 25 March 2009: "If we decrease the use of carbon dioxide, are we not taking away plant food from the atmosphere?"

The legion of climate change skeptics are active across the world, and they happily play with our children's future.

The clock is ticking for the planet, but the climate change skeptics simply do not care. The vested interests at work are simply too great.

It's been more than 30 years since the first World Climate Conference called on governments to guard against potential climate hazards.

It's been 20 years since the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was formed and produced its first report.

17 years ago, in 1992, the international community acknowledged the importance of tackling climate change at the Rio Earth Summit and created the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

And the most recent IPCC scientific conclusion in 2007 was that "warming of the climate system is unequivocal" and the "increase in global average temperatures since the mid 20th century is very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations."

This is the conclusion of 4,000 scientists appointed by governments from virtually every country in the world, and the term "very likely" is defined in the scientific conclusion of this report as being 90 per cent probable.

Attempts by politicians in this country and others to present what is an overwhelming global scientific consensus as little more than an unfolding debate, with two sides evenly represented in a legitimate scientific argument, are nothing short of intellectually dishonest. They are a political attempt to subvert what is now a longstanding scientific consensus, an attempt to twist the agreed science in the direction of a predetermined political agenda to kill climate change action.

It reminds me of the efforts of the smoking lobby decades ago as they tried for years to politically subvert by so-called scientific means that there was any link between smoking and lung cancer.

Put more simply: these climate change sceptics around the world would be laughable if they were not so politically powerful - particularly in the ranks of conservative parties.

The second group of do-nothing climate change skeptics are those who purport to accept the scientific consensus, but in the next breath are unwilling to support any of the practicable plans of action that would actually do something about climate change. This group plays lip service to the climate change science but when push comes to shove refuse to support climate change action. In Australia, these naysayers have successfully blocked the development of an emissions trading scheme for more than a decade.

After 12 years of inaction under the previous government, this government has worked to build a national consensus around our Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme. We took the concept to the people at the 2007 election, and since then we have methodically, clearly and comprehensively worked towards passage of our scheme.

The Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme Green Paper was released on 16 June 2008.

The Garnaut Climate Change Review was released on 30 September 2008.

The Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme White Paper was released on 15 December 2008.

The Draft Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme legislation was released in March.

There have been numerous Senate Inquiries.

There have also been numerous industry consultations.

As of May 2009, the Government had built wide support for action on climate through a carbon pollution reduction scheme.

There was broad business, environmental and community support from:

* The Business Council of AustraliaToday, after so many reports, reviews, consultations, not to mention the small matter of an election - the overwhelming need for Australia to tackle the great challenge of our generation is being frustrated by the do-nothing climate change skeptics.

* The Australian Industry group

* The Climate Institute

* The Australian Conservation Foundation

* The World Wildlife Fund

* The Australian Council of Social Services representing lower income Australians.

As recently as last year, the Leader of the Opposition was emphatic in his support for an emissions trading scheme. He said it was the "central mechanism" in the fight against climate change.

Speaking at the National Press Club in May last year, he stated: "The Emissions Trading Scheme is the central mechanism to decarbonise our economy." (21 May 2008)

A few days later, he said: "The biggest element in the fight against climate change has to be the emissions-trading scheme." (HANSARD - 26 MAY 2008)

But still today, after so many reports and consultations, the Liberal Party, the National Party and other opponents of action raise objections to the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme.

Their objections fall into three categories:

* Some argue that the cost is too high in terms of its impact on our economy.Let us take each of these in turn.

* Others argue that the cost is too high in terms of its impact on households.

* And others object to the system of global emissions trading because they believe it will unjustifiably transfer money and power from rich countries to poor countries.

First is the cost to our economy and jobs.

This has been a constant theme of the Liberal and National Parties' attacks on the CPRS. Mr Turnbull said the CPRS "is guaranteed to slow our economic recovery, cost us jobs."

And the de facto leader of the National Party, Barnaby Joyce, refers to the emissions trading scheme as the "employment termination scheme" - whereas I thought any self-respecting National Party leader would be out there standing up for farmers facing 40 to 80 per cent more drought in the future, rather than betraying them.

The facts about the impact of unmitigated climate change on the one hand and the CPRS on the other tell a very different story, but that eternal motto of the Liberal and National Parties is never let the facts stand in the road of a good fear campaign - whether it's debt, border security or climate change.

Here are the facts.

Treasury modelling done in 2008 demonstrates Australia can continue to achieve strong trend economic growth while making significant cuts in emissions through the CPRS. Treasury modelling also demonstrates that all major employment sectors grow over the years to 2020 - substantially increasing employment from today's levels. Treasury modelling also projects that clean industries will create sustainable jobs of the future - in fact by 2050 the renewable electricity sector will be 30 times larger than it is today.

Another element of the Liberal and National fear campaign about the design of the CPRS is that it will impose unmanageable cost on households.

Again, Senator Joyce - fearmonger in chief on climate change, he who therefore betrays the real interests of Australian farmers - puts the position of the Liberal and National parties as follows: "If you live in a cave with a candle you would probably be OK, but if your house is wired up for power then every electrical appliance will be attached to a power generator which in all likelihood will pay a tax and that tax will be passed on to you, the consumer." (Joyce - 27 JULY 2009)

Again, the facts on the true household costs and impacts of the CPRS tell a different story. Treasury modelling again demonstrates that the price impact of the CPRS is modest. The CPRS is expected to raise household prices by 0.4 per cent in 2011-12 and 0.8 per cent in 2012-13, and the government has provided household compensation to help assist with these modest cost rises.

Pensioners, seniors, carers and people with disability and low-income households will receive additional support to fully meet the expected overall increase in the cost of living flowing from the scheme. Middle-income households will also receive additional support to help meet the expected overall increase in the cost of living flowing from the scheme.

A third argument from those who quibble with the design of the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme is that the international design aspects of the scheme are flawed.

Lord Christopher Monckton - a former adviser to Margaret Thatcher - was quoted this week in the Australian press by Janet Albrechtsen. Lord Monckton describes the potential Copenhagen agreement as a plan to set up a transnational "government" on a scale the world has never before seen. Enter the "world government" conspiracy theorists.

Lord Monckton also publicly warned Americans that "in the next few weeks, unless you stop it, your president will sign your freedom, your democracy and your prosperity away forever."

Janet Albrechtsen, in her understated neo-conservative way, refers to the potential Copenhagen agreement as a UN "power grab". This gaggle of world government conspiracy theorists are so far out there on the far right, that they rub up next to the global anarchists of the far left.

Those who argue that any multilateral action is by definition evil.

Those who argue that climate change does not represent a global market failure.

Those who argue that somehow the market will magically solve the problem.

And that uncoordinated national actions will fix the problem.

Without answering the basic logical question of how can we deal with an existential challenge for the whole planet which lies beyond the capacity of any individual national action to address.

The climate change deniers now form the comfortable bedfellows of the global conspiracy theorists - in total bald-faced denial of global scientific, economic and environmental reality. These arguments - thinly veiled attempts to create a new climate change global conspiracy theory - are now being used in Australia.

Like the arguments from climate change deniers, these arguments have zero basis in evidence.

Where is their equivalent evidence basis to Treasury modelling published by the Government of the industry and employment impacts of climate change?

Where is their equivalent evidence basis to Treasury modelling published by the Government on the cost impacts for households from the CPRS - and on the adequacy of the compensation arrangements put in place by the Government in our White Paper?

The answer once again is there is none.

Where is the evidence basis offered by the new league of world government conspiracy theorists that climate change can be effectively dealt with by market means or by uncoordinated national means?

Answer - there is none.

The truth is that the do-nothing climate change skeptics offer no alternative official body of evidence from any credible government in the world.

Absolutely none. The truth is they offer zero evidence.

Instead they offer maximum fear, the universal conservative stock in trade.

And by doing so, these do-nothing climate change skeptics are prepared to destroy our children's future.

The third group of climate deniers are those who pretend to accept the science but then urge delay because they don't want their country to be the first to act.

In Australia there was once a political consensus resisting this parochial view.

The Shergold Report commissioned by John Howard and written by the head of the Prime Minister's department recommended that Australia should not wait for the rest of the world to act: "... waiting until a truly global response emerges before imposing an emissions cap will place costs on Australia by increasing business uncertainty and delaying or losing investment." (Report of the Prime Ministerial Task Group on Emissions Trading, June 2007, p.6)

The current Leader of the Opposition also stated that a domestic ETS would help in international negotiations too: "... our first hand experience in implementing ... an emissions trading system would be of considerable assistance in our international discussions and negotiation aimed at achieving an effective global agreement." (Turnbull - SMH Opinion Piece - 9 July 2008)

Then the Leader of the Opposition stated he no longer supported domestic action before Copenhagen: "I would not find, I would not support finalising the design this year. Even the best designed scheme in theory needs to have the input of the knowledge of what happens at Copenhagen and what the Americans will do." (AM - 16 MARCH 2009)

Seven times the Liberals and Nationals have promised to make a decision on their policy on climate change - and seven times they have delayed.

1. In December 2007 they said wait for Garnaut.It is an endless cycle of delay - and I am sure that with December almost upon us, the eighth excuse cannot be far away - which will be to wait until the next year or the year after until all the rest of the world has acted at which time Australia will act.

2. In September 2008 they said wait for Treasury modelling.

3. In September 2008 they said wait for the White Paper.

4. In December 2008 they said wait until the Pearce Report.

5. In April 2009 they said wait for the Senate Inquiry.

6. In May 2009 they said wait for the Productivity Commission - forgetting that the Productivity Commission already made a submission on emissions trading to the Howard Government's Shergold Report.

7. Now the Liberals and National have said wait for Copenhagen and for President Obama's scheme.

What absolute political cowardice. What an absolute failure of leadership. What an absolute failure of logic. The inescapable logic of this approach is that if every nation makes the decision not to act until others have done so, then no nation will ever act.

The immediate and inevitable consequence of this logic - if echoed in other countries - is that there will be no global deal as each nation says to its domestic constituencies that they cannot act because others have not acted.

The result is a negotiating stalemate. A permanent standoff.

And this of course is the consistent ambition of all three groups of do-nothing climate change deniers.

As we approach Copenhagen, it becomes clearer that the domestic political pressure produced by the climate change skeptics now has profound global consequences by reducing the momentum towards an ambitious global deal. The argument that we must not act until others do is an argument that has been used by political cowards since time immemorial - both of the left and the right.

To take just one example, it has been used as an argument to retain protectionism, stifling economic growth and global competition, and preventing the spread of global prosperity.

As many have noted, it is the international political version of the prisoner's dilemma. If we allow our actions to be dictated by what we falsely conclude to be in our narrow self-interest, then we harm not just others but ourselves as well because climate change inaction harms us as well.

Climate change deniers are small in number, but they are too dangerous to be ignored. They are well resourced and well represented by political conservatives in many, many countries.

And the danger they pose is this - by collapsing political momentum towards national and global action on climate change, they collapse global political will to act at all. They are the stick that gets stuck in the wheel, that despite its size may yet bring the train to a complete stop.

And that is what they want, because they are driven by a narrowly defined self interest of the present and are utterly contemptuous towards our children's interest in the future.

This brigade of do-nothing climate change skeptics are dangerous because if they succeed, then it is all of us who will suffer. Our children. And our grandchildren. If we fail, then it will be a failure that will echo through future generations.

The consequences for Australia of failing to act domestically and internationally on climate change are severe. We know from formal global and national economic modelling that the costs of inaction are greater than the costs of acting. Treasury modelling from October 2008 shows that economies that defer action on climate change face long-term costs around 15 per cent higher than those that take action now.

The sooner we act, the better placed our companies will be to benefit from new emerging global markets, and to benefit from the economic gains from improved efficiency. Moving to a low pollution economy will require significant investment in renewable energy, carbon capture and storage, energy efficiency and other low emissions technologies.

We need to start giving the signal to investors that they need to factor the price of carbon into their decisions to make the investments we need. Importantly, business needs certainty to make these investments.

As Greig Gailey, former President of the Business Council of Australia said: "Only business can make the many investments needed to transition Australia to a low carbon economy. To do this business needs certainty."

Without passage of the CPRS there will be no certainty for business. That is why business groups like the Business Council of Australia and the Australian Industry Group want to see the major parties come together and vote on the CPRS this year.

Heather Ridout, Chief Executive of the Australian Industry Group said: "... many of our members are telling us that they are holding off making investments until there is a greater degree of clarity around domestic climate change legislation." (ADECCO Group Australia Breakfast - 15 October 2009)

Russell Caplan, Chairman of Shell Australia, said: "... we believe a far greater risk is that Australia misses the opportunity to put a policy framework in place to deal with this issue. This would create a climate of continuing uncertainty for industry and potentially delay the massive investments required." (BRW - 6 August 2009)

These are the implications for Australia. These are the political challenges we now face both at home and abroad. But my unequivocal message to the nation today is that this nation Australia will not be deterred. Our course is clear. That is why this government will press forward with our plan to tackle climate change domestically and globally. Domestically we will press forward with the passage of the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme. It will be voted on in the House in the week beginning Monday November 16. It will be introduced into the Senate immediately after the vote in the House. It will then be voted on in the Senate in the week beginning 23 November.

We welcome the Opposition's recent cooperation and I'm pleased to hear from Minister Wong that negotiations are proceeding in good faith. I'd like to personally commend the Member for Groome for his genuine efforts to engage with the Government in good faith to reach a reasonable outcome with the Government that will finally deliver action on Climate Change.

We are of course concerned by the comments of the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate that "even if the government accepts all our amendments, we may well still vote against the bill." (NICK MINCHIN- 2UE- 30 OCTOBER 2009)

The do-nothing climate change skeptics are still alive and well in the Coalition. After 12 years of inaction, and after two years of preparation, the nation demands a genuine timetable and good faith negotiations to give business the certainty they need with climate change.

The Australian Government is also committed to intensively engaging to support an ambitious agreement in Copenhagen.

At Copenhagen we need an ambitious agreement on mitigation, adaptation, finance and technology.

As UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon said yesterday, the formal UN negotiations are moving slowly.

The UN Secretary-General has said we must maximise the agreement we can reach in Copenhagen. They can resolve some issues, but not others.

Now is time for strenuous efforts by all leaders and ministers.

Denmark's Prime Minister Rasmussen is engaging a growing number of leaders - in the Copenhagen Commitment Circle - to accelerate engagement by leaders.

Australia is committed to playing a leadership role and has joined Mexico and the UN Secretary-General in the initial group of 'friends of the Chair' to help build consensus and draw out concrete commitments from across the world.

In July this year at the G8 meetings in L'Aquila, Australia helped form a 2 degree Celsius 450 ppm ambition for global action on climate change, and it was at this meeting that Australia launched the Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute, a concrete initiative to make CCS technology a reality.

Australia is currently chair of the Pacific Island Forum which this year delivered the Pacific Leaders' Climate Change Call to Action demanding urgent action on a real threat to the viability of some Pacific communities.

In September, Australia at the request of the UN Secretary-General co-chaired a roundtable at the UN Special Session on Climate Change - with a view to driving a sense of political urgency with other leaders, and representing the views of the Pacific.

Australia has launched the Forest Carbon Partnerships with Indonesia and Papua New Guinea - an initiative providing policy and technical support to protect the great forests in our neighbourhood.

And Australia has established a $150 million Climate Change Adaptation Fund - supporting vulnerable nations dealing with the real impact of climate change, with a strong focus on the Pacific.

For years - and then, with increasing intensity, in recent months - do-nothing climate change skeptics have been mounting a systematic campaign against action on climate change.

Their aim is not to convince every person on earth of the follies of acting on climate change. Their aim is to erode just enough of the political will that action becomes impossible.

By slowing the actions of each individual country, they aim to slowly drag global negotiations on climate change to a standstill. By hampering decisive action at a national level, they aim to make it impossible at an international level.

If Copenhagen does not deliver the outcome we so urgently need, no individual climate change skeptic will be responsible, but each of them will have played their part.

The corrosive effect of climate skeptics eroding the political will to act may be the disintegration of any possibility of meaningful action on climate change.

In this debate the climate change skeptics have erected an intellectual house of cards based on one simple premise: that the cost of not acting is nothing.

When you boil down their arguments, their world government conspiracy theories and their back of the envelope calculations - that in its starkest simplicity and entirety is what is left: that the cost of not acting is nothing.

That is the simplest premise upon which the scepticism of Malcolm, Barnaby, Andrew, Alan, Janet and even Lord Monckton is based. They cling to that single premise like a polar bear clings to a melting iceberg.

Without that premise, their scepticism is sunk. Malcolm, Barnaby, Andrew, Janet and the Thatcherite Lord Monckton are betting the house on that simple premise that the cost of not acting is nothing.

For people who claim to hold the conservative torch, their scepticism is in fact radical in its riskiness and recklessness. By deliberately undermining and eroding the capacity to achieve both domestic and international action on climate change the skeptics are attempting to force the world to take the single most reckless bet in our long history.

They are betting our future, the future of our children and our grandchildren, and they are doing so based on their own personal intuitions, their personal prejudices and their deeply ingrained political prejudices.

And they are doing so in the total absence of any genuine body of evidence.

Climate change skeptics in all their guises and disguises are not conservatives. They are radicals.

They are reckless gamblers who are betting all our futures on their arrogant assumption that their intuitions should triumph over the evidence.

The logic of these skeptics belongs in a casino, not a science lab, and not in the ranks of any responsible government.

Malcolm, Barnaby, Andrew, Janet, even Lord Monckton shouldn't even bother with the pretence of science and just admit the currency of their prescription for inaction has all the legitimacy of a roulette wheel.

Basically, let's just sit back, do nothing and see what happens.

The alternative - our alternative - is to base policy on the evidence. No responsible government confronted with the evidence delivered by the 4,000 scientists associated with the international panel could then in conscience choose not to act. In any public company, it would represent a gross contempt of the most basic fiduciary duty.

Malcolm and Barnaby might like to bet the future of Australia on the off chance of winning an election, but this Government will not.

A fairly well-known bloke once said that when gambling:

You've got to know when to hold 'em, know when to fold 'em.My message to the climate change skeptics, to the big betters and the big risk takers is this:

Know when to walk away, know when to run.

You are betting our children's future and the future of our grandchildren. You are betting our jobs, our houses, our farms, our reefs, our economy and our future on an intuition - on a gut feeling; on a political prejudice you have about science. That is too big a risk, too radical a departure from the basic conservative principles of public policy. Malcolm, Barnaby, Andrew, Janet - stop gambling with our future. You've got to know when to fold 'em - and for the skeptics, that time has come.

The Government I lead will act.

***************************************************************************

Catch-22, Joseph Heller, 1955-1961.

: nine. MAJOR MAJOR MAJOR MAJOR

Major Major Major Major had had a difficult time from the start.

Like Minniver Cheevy, he had been born too late—exactly thirty-six hours too late for the physical well-being of his mother, a gentle, ailing woman who, after a full day and a half's agony in the rigors of childbirth, was depleted of all resolve to pursue further the argument over the new child's name. In the hospital corridor, her husband moved ahead with the unsmiling determination of someone who knew what he was about. Major Major's father was a towering, gaunt man in heavy shoes and a black woolen suit. He filled out the birth certificate without faltering, betraying no emotion at all as he handed the completed form to the floor nurse. The nurse took it from him without comment and padded out of sight. He watched her go, wondering what she had on underneath.

Back in the ward, he found his wife lying vanquished beneath the blankets like a desiccated old vegetable, wrinkled, dry and white, her enfeebled tissues absolutely still. Her bed was at the very end of the ward, near a cracked window thickened with grime. Rain splashed from a moiling sky and the day was dreary and cold. In other parts of the hospital chalky people with aged, blue lips were dying on time. The man stood erect beside the bed and gazed down at the woman a long time.

"I have named the boy Caleb," he announced to her finally in a soft voice. "In accordance with your wishes." The woman made no answer, and slowly the man smiled. He had planned it all perfectly, for his wife was asleep and would never know that he had lied to her as she lay on her sickbed in the poor ward of the county hospital.

From this meager beginning had sprung the ineffectual squadron commander who was now spending the better part of each working day in Pianosa forging Washington Irving's name to official documents. Major Major forged diligently with his left hand to elude identification, insulated against intrusion by his own undesired authority and camouflaged in his false mustache and dark glasses as an additional safeguard against detection by anyone chancing to peer in through the dowdy celluloid window from which some thief had carved out a slice. In between these two low points of his birth and his success lay thirty-one dismal years of loneliness and frustration.

Major Major had been born too late and too mediocre. Some men are born mediocre, some men achieve mediocrity, and some men have mediocrity thrust upon them. With Major Major it had been all three. Even among men lacking all distinction he inevitably stood out as a man lacking more distinction than all the rest, and people who met him were always impressed by how unimpressive he was.

Major Major had three strikes on him from the beginning—his mother, his father and Henry Fonda, to whom he bore a sickly resemblance almost from the moment of his birth. Long before he even suspected who Henry Fonda was, he found himself the subject of unflattering comparisons everywhere he went. Total strangers saw fit to deprecate him, with the result that he was stricken early with a guilty fear of people and an obsequious impulse to apologize to society for the fact that he was not Henry Fonda. It was not an easy task for him to go through life looking something like Henry Fonda, but he never once thought of quitting, having inherited his perseverance from his father, a lanky man with a good sense of humor.

Major Major's father was a sober God-fearing man whose idea of a good joke was to lie about his age. He was a long-limbed farmer, a God-fearing, freedom-loving, law-abiding rugged individualist who held that federal aid to anyone but farmers was creeping socialism. He advocated thrift and hard work and disapproved of loose women who turned him down. His specialty was alfalfa, and he made a good thing out of not growing any. The government paid him well for every bushel of alfalfa he did not grow. The more alfalfa he did not grow, the more money the government gave him, and he spent every penny he didn't earn on new land to increase the amount of alfalfa he did not produce. Major Major's father worked without rest at not growing alfalfa. On long winter evenings he remained indoors and did not mend harness, and he sprang out of bed at the crack of noon every day just to make certain that the chores would not be done. He invested in land wisely and soon was not growing more alfalfa than any other man in the county. Neighbors sought him out for advice on all subjects, for he had made much money and was therefore wise. "As ye sow, so shall ye reap," he counseled one and all, and everyone said, "Amen."

Major Major's father was an outspoken champion of economy in government, provided it did not interfere with the sacred duty of government to pay farmers as much as they could get for all the alfalfa they produced that no one else wanted or for not producing any alfalfa at all. He was a proud and independent man who was opposed to unemployment insurance and never hesitated to whine, whimper, wheedle, and extort for as much as he could get from whomever he could. He was a devout man whose pulpit was everywhere.

"The Lord gave us good farmers two strong hands so that we could take as much as we could grab with both of them," he preached with ardor on the courthouse steps or in front of the A&P as he waited for the bad-tempered gum-chewing young cashier he was after to step outside and give him a nasty look. "If the Lord didn't want us to take as much as we could get," he preached, "He wouldn't have given us two good hands to take it with." And the others murmured, "Amen."

Major Major's father had a Calvinist's faith in predestination and could perceive distinctly how everyone's misfortunes but his own were expressions of God's will. He smoked cigarettes and drank whiskey, and he thrived on good wit and stimulating intellectual conversation, particularly his own when he was lying about his age or telling that good one about God and his wife's difficulties in delivering Major Major. The good one about God and his wife's difficulties had to do with the fact that it had taken God only six days to produce the whole world, whereas his wife had spent a full day and a half in labor just to produce Major Major. A lesser man might have wavered that day in the hospital corridor, a weaker man might have compromised on such excellent substitutes as Drum Major, Minor Major, Sergeant Major, or C. Sharp Major, but Major Major's father had waited fourteen years for just such an opportunity, and he was not a person to waste it. Major Major's father had a good joke about opportunity. " Opportunity only knocks once in this world," he would say. Major Major's father repeated this good joke at every opportunity.

Being born with a sickly resemblance to Henry Fonda was the first of along series of practical jokes of which destiny was to make Major Major the unhappy victim throughout his joyless life. Being born Major Major Major was the second. The fact that he had been born Major Major Major was a secret known only to his father. Not until Major Major was enrolling in kindergarten was the discovery of his real name made, and then the effects were disastrous. The news killed his mother, who just lost her will to live and wasted away and died, which was just fine with his father, who had decided to marry the bad-tempered girl at the A&P if he had to and who had not been optimistic about his chances of getting his wife off the land without paying her some money or flogging her.

On Major Major himself the consequences were only slightly less severe. It was a harsh and stunning realization that was forced upon him at so tender an age, the realization that he was not, as he had always been led to believe, Caleb Major, but instead was some total stranger named Major Major Major about whom he knew absolutely nothing and about whom nobody else had ever heard before. What playmates he had withdrew from him and never returned, disposed, as they were, to distrust all strangers, especially one who had already deceived them by pretending to be someone they had known for years. Nobody would have anything to do with him. He began to drop things and to trip. He had a shy and hopeful manner in each new contact, and he was always disappointed. Because he needed a friend so desperately, he never found one. He grew awkwardly into a tall, strange, dreamy boy with fragile eyes and a very delicate mouth whose tentative, groping smile collapsed instantly into hurt disorder at every fresh rebuff.

He was polite to his elders, who disliked him. Whatever his elders told him to do, he did. They told him to look before he leaped, and he always looked before he leaped. They told him never to put off until the next day what he could do the day before, and he never did. He was told to honor his father and his mother, and he honored his father and his mother. He was told that he should not kill, and he did not kill, until he got into the Army. Then he was told to kill, and he killed. He turned the other cheek on every occasion and always did unto others exactly as he would have had others do unto him. When he gave to charity, his left hand never knew what his right hand was doing. He never once took the name of the Lord his God in vain, committed adultery or coveted his neighbor's ass. In fact, he loved his neighbor and never even bore false witness against him. Major Major's elders disliked him because he was such a flagrant nonconformist.

Since he had nothing better to do well in, he did well in school. At the state university he took his studies so seriously that he was suspected by the homosexuals of being a Communist and suspected by the Communists of being a homosexual. He majored in English history, which was a mistake.

"English history!" roared the silver-maned senior Senator from his state indignantly. "What's the matter with American history? American history is as good as any history in the world!"

Major Major switched immediately to American literature, but not before the F.B.I. had opened a file on him. There were six people and a Scotch terrier inhabiting the remote farmhouse Major Major called home, and five of them and the Scotch terrier turned out to be agents for the F.B.I. Soon they had enough derogatory information on Major Major to do whatever they wanted to with him. The only thing they could find to do with him, however, was take him into the Army as a private and make him a major four days later so that Congressmen with nothing else on their minds could go trotting back and forth through the streets of Washington, D.C., chanting, "Who promoted Major Major? Who promoted Major Major?"

Actually, Major Major had been promoted by an I.B.M. machine with a sense of humor almost as keen as his father's. When war broke out, he was still docile and compliant. They told him to enlist, and he enlisted. They told him to apply for aviation cadet training, and he applied for aviation cadet training, and the very next night found himself standing barefoot in icy mud at three o'clock in the morning before a tough and belligerent sergeant from the Southwest who told them he could beat hell out of any man in his outfit and was ready to prove it. The recruits in his squadron had all been shaken roughly awake only minutes before by the sergeant's corporals and told to assemble in front of the administration tent. It was still raining on Major Major. They fell into ranks in the civilian clothes they had brought into the Army with them three days before. Those who had lingered to put shoes and socks on were sent back to their cold, wet, dark tents to remove them, and they were all barefoot in the mud as the sergeant ran his stony eyes over their faces and told them he could beat hell out of any man in his outfit. No one was inclined to dispute him.

Major Major's unexpected promotion to major the next day plunged the belligerent sergeant into a bottomless gloom, for he was no longer able to boast that he could beat hell out of any man in his outfit. He brooded for hours in his tent like Saul, receiving no visitors, while his elite guard of corporals stood discouraged watch outside. At three o'clock in the morning he found his solution, and Major Major and the other recruits were again shaken roughly awake and ordered to assemble barefoot in the drizzly glare at the administration tent, where the sergeant was already waiting, his fists clenched on his hips cockily, so eager to speak that he could hardly wait for them to arrive.

"Me and Major Major," he boasted, in the same tough, clipped tones of the night before, "can beat hell out of any man in my outfit."

The officers on the base took action on the Major Major problem later that same day. How could they cope with a major like Major Major? To demean him personally would be to demean all other officers of equal or lesser rank. To treat him with courtesy, on the other hand, was unthinkable. Fortunately, Major Major had applied for aviation cadet training. Orders transferring him away were sent to the mimeograph room late in the afternoon, and at three o'clock in the morning Major Major was again shaken roughly awake, bidden Godspeed by the sergeant and placed aboard a plane heading west.

Lieutenant Scheisskopf turned white as a sheet when Major Major reported to him in California with bare feet and mudcaked toes. Major Major had taken it for granted that he was being shaken roughly awake again to stand barefoot in the mud and had left his shoes and socks in the tent. The civilian clothing in which he reported for duty to Lieutenant Scheisskopf was rumpled and dirty. Lieutenant Scheisskopf, who had not yet made his reputation as a parader, shuddered violently at the picture Major Major would make marching barefoot in his squadron that coming Sunday.

"Go to the hospital quickly," he mumbled, when he had recovered sufficiently to speak, "and tell them you're sick. Stay there until your allowance for uniforms catches up with you and you have some money to buy some clothes. And some shoes. Buy some shoes."

"Yes, sir."

"I don't think you have to call me 'sir,' sir," Lieutenant Scheisskopf pointed out. "You outrank me."

"Yes, sir. I may outrank you, sir, but you're still my commanding officer."

"Yes, sir, that's right," Lieutenant Scheisskopf agreed. "You may outrank me, sir, but I'm still your commanding officer. So you better do what I tell you, sir, or you'll get into trouble. Go to the hospital and tell them you're sick, sir. Stay there until your uniform allowance catches up with you and you have some money to buy some uniforms."

"Yes, sir."

"And some shoes, sir. Buy some shoes the first chance you get, sir."

"Yes, sir. I will, sir."

"Thank you, sir."

Life in cadet school for Major Major was no different than life had been for him all along. Whoever he was with always wanted him to be with someone else. His instructors gave him preferred treatment at every stage in order to push him along quickly and be rid of him. In almost no time he had his pilot's wings and found himself overseas, where things began suddenly to improve. All his life, Major Major had longed for but one thing, to be absorbed, and in Pianosa, for a while, he finally was. Rank meant little to the men on combat duty, and relations between officers and enlisted men were relaxed and informal. Men whose names he didn't even know said "Hi" and invited him to go swimming or play basketball. His ripest hours were spent in the day-long basketball games no one gave a damn about winning. Score was never kept, and the number of players might vary from one to thirty-five. Major Major had never played basketball or any other game before, but his great, bobbing height and rapturous enthusiasm helped make up for his innate clumsiness and lack of experience. Major Major found true happiness there on the lopsided basketball court with the officers and enlisted men who were almost his friends. If there were no winners, there were no losers, and Major Major enjoyed every gamboling moment right up till the day Colonel Cathcart roared up in his jeep after Major Duluth was killed and made it impossible for him ever to enjoy playing basketball there again.

"You're the new squadron commander," Colonel Cathcart had shouted rudely across the railroad ditch to him. "But don't think it means anything, because it doesn't. All it means is that you're the new squadron commander."

Colonel Cathcart had nursed an implacable grudge against Major Major for a long time. A superfluous major on his rolls meant an untidy table of organization and gave ammunition to the men at Twenty-seventh Air Force Headquarters who Colonel Cathcart was positive were his enemies and rivals. Colonel Cathcart had been praying for just some stroke of good luck like Major Duluth's death. He had been plagued by one extra major; he now had an opening for one major. He appointed Major Major squadron commander and roared away in his jeep as abruptly as he had come.

For Major Major, it meant the end of the game. His face flushed with discomfort, and he was rooted to the spot in disbelief as the rain clouds gathered above him again. When he turned to his teammates, he encountered a reef of curious, reflective faces all gazing at him woodenly with morose and inscrutable animosity. He shivered with shame. When the game resumed, it was not good any longer. When he dribbled, no one tried to stop him; when he called for a pass, whoever had the ball passed it; and when he missed a basket, no one raced him for the rebound. The only voice was his own. The next day was the same, and the day after that he did not come back.

Almost on cue, everyone in the squadron stopped talking to him and started staring at him. He walked through life self-consciously with downcast eyes and burning cheeks, the object of contempt, envy, suspicion, resentment and malicious innuendo everywhere he went. People who had hardly noticed his resemblance to Henry Fonda before now never ceased discussing it, and there were even those who hinted sinisterly that Major Major had been elevated to squadron commander because he resembled Henry Fonda. Captain Black, who had aspired to the position himself, maintained that Major Major really was Henry Fonda but was too chickenshit to admit it.

Major Major floundered bewilderedly from one embarrassing catastrophe to another. Without consulting him, Sergeant Towser had his belongings moved into the roomy trailer Major Duluth had occupied alone, and when Major Major came rushing breathlessly into the orderly room to report the theft of his things, the young corporal there scared him half out of his wits by leaping to his feet and shouting "Attention!" the moment he appeared. Major Major snapped to attention with all the rest in the orderly room, wondering what important personage had entered behind him. Minutes passed in rigid silence, and the whole lot of them might have stood there at attention till doomsday if Major Danby had not dropped by from Group to congratulate Major Major twenty minutes later and put them all at ease.

Major Major fared even more lamentably at the mess hall, where Milo, his face fluttery with smiles, was waiting to usher him proudly to a small table he had set up in front and decorated with an embroidered tablecloth and a nosegay of posies in a pink cut-glass vase. Major Major hung back with horror, but he was not bold enough to resist with all the others watching. Even Havermeyer had lifted his head from his plate to gape at him with his heavy, pendulous jaw. Major Major submitted meekly to Milo 's tugging and cowered in disgrace at his private table throughout the whole meal. The food was ashes in his mouth, but he swallowed every mouthful rather than risk offending any of the men connected with its preparation. Alone with Milo later, Major Major felt protest stir for the first time and said he would prefer to continue eating with the other officers. Milo told him it wouldn't work.

"I don't see what there is to work," Major Major argued. "Nothing ever happened before." "You were never the squadron commander before."

"Major Duluth was the squadron commander and he always ate at the same table with the rest of the men."

"It was different with Major Duluth, Sir."

"In what way was it different with Major Duluth?"

"I wish you wouldn't ask me that, sir," said Milo.

"Is it because I look like Henry Fonda?" Major Major mustered the courage to demand.

"Some people say you are Henry Fonda," Milo answered.

"Well, I'm not Henry Fonda," Major Major exclaimed, in a voice quavering with exasperation. "And I don't look the least bit like him. And even if I do look like Henry Fonda, what difference does that make?"

"It doesn't make any difference. That's what I'm trying to tell you, sir. It's just not the same with you as it was with Major Duluth."

And it just wasn't the same, for when Major Major, at the next meal, stepped from the food counter to sit with the others at the regular tables, he was frozen in his tracks by the impenetrable wall of antagonism thrown up by their faces and stood petrified with his tray quivering in his hands until Milo glided forward wordlessly to rescue him, by leading him tamely to his private table. Major Major gave up after that and always ate at his table alone with his back to the others. He was certain they resented him because he seemed too good to eat with them now that he was squadron commander. There was never any conversation in the mess tent when Major Major was present. He was conscious that other officers tried to avoid eating at the same time, and everyone was greatly relieved when he stopped coming there altogether and began taking his meals in his trailer.

Major Major began forging Washington Irving's name to official documents the day after the first C.I.D. man showed up to interrogate him about somebody at the hospital who had been doing it and gave him the idea. He had been bored and dissatisfied in his new position. He had been made squadron commander but had no idea what he was supposed to do as squadron commander, unless all he was supposed to do was forge Washington Irving's name to official documents and listen to the isolated clinks and thumps of Major—de Coverley's horseshoes falling to the ground outside the window of his small office in the rear of the orderly-room tent. He was hounded incessantly by an impression of vital duties left unfulfilled and waited in vain for his responsibilities to overtake him. He seldom went out unless it was absolutely necessary, for he could not get used to being stared at. Occasionally, the monotony was broken by some officer or enlisted man Sergeant Towser referred to him on some matter that Major Major was unable to cope with and referred right back to Sergeant Towser for sensible disposition. Whatever he was supposed to get done as squadron commander apparently was getting done without any assistance from him. He grew moody and depressed. At times he thought seriously of going with all his sorrows to see the chaplain, but the chaplain seemed so overburdened with miseries of his own that Major Major shrank from adding to his troubles. Besides, he was not quite sure if chaplains were for squadron commanders.

He had never been quite sure about Major—de Coverley, either, who, when he was not away renting apartments or kidnaping foreign laborers, had nothing more pressing to do than pitch horseshoes. Major Major often paid strict attention to the horseshoes falling softly against the earth or riding down around the small steel pegs in the ground. He peeked out at Major—de Coverley for hours and marveled that someone so august had nothing more important to do. He was often tempted to join Major—de Coverley, but pitching horseshoes all day long seemed almost as dull as signing "Major Major Major" to official documents, and Major– de Coverley's countenance was so forbidding that Major Major was in awe of approaching him.

Major Major wondered about his relationship to Major—de Coverley and about Major—de Coverley's relationship to him. He knew that Major—de Coverley was his executive officer, but he did not know what that meant, and he could not decide whether in Major—de Coverley he was blessed with a lenient superior or cursed with a delinquent subordinate. He did not want to ask Sergeant Towser, of whom he was secretly afraid, and there was no one else he could ask, least of all Major—de Coverley. Few people ever dared approach Major—de Coverley about anything and the only officer foolish enough to pitch one of his horseshoes was stricken the very next day with the worst case of Pianosan crud that Gus or Wes or even Doc Daneeka had ever seen or even heard about. Everyone was positive the disease had been inflicted upon the poor officer in retribution by Major—de Coverley, although no one was sure how.