Up, Down, Appendices, Postscript.

Good Friday, Earth Day 2011, Queen's Park, Toronto:

Good Friday, Earth Day 2011, Queen's Park, Toronto:"Oh, that's good," I thought as I walked up the hill, "couple'a hundred at least."

And looking at the police keeping their distance ... I wondered if it would be maybe possible to talk with one of them?

And looking at the police keeping their distance ... I wondered if it would be maybe possible to talk with one of them?Mingling in the crowd (without my glasses on) I talked with a young woman and her horse, explaining what 350 means, and what a nexus is; and she then explained to me that they were not there on the nuclear question but were protesting the 1,000 hectare (that's 2,300 acres!) Mega-Quarry planned by The Highland Companies (aka 1712665 Ontario Inc. aka 3191574 Nova Scotia Company) for Horning's Mills north of Shelburne in Melancthon and Mulmur Townships - near Orangeville 60 miles north-west of Toronto, here's a map. More on this below.

So anyway ... I wandered over to the UofT Vote Mob where I did meet a policeman, all by himself, and we had a ten minute conversation. He didn't understand (or pretended not to understand) why I was upset over the behaviour of police at the G20. "Shit happens," was his view. What he wanted to know was who I was 'with'? and when I said I was alone he lost interest. At least he was civil. He made a good point on name tags: that maybe number tags would be better, to protect police from subsequent harassment. OK I guess.

So anyway ... I wandered over to the UofT Vote Mob where I did meet a policeman, all by himself, and we had a ten minute conversation. He didn't understand (or pretended not to understand) why I was upset over the behaviour of police at the G20. "Shit happens," was his view. What he wanted to know was who I was 'with'? and when I said I was alone he lost interest. At least he was civil. He made a good point on name tags: that maybe number tags would be better, to protect police from subsequent harassment. OK I guess. And finally I found the very small group of nuclear protesters. What can I possibly say?

And finally I found the very small group of nuclear protesters. What can I possibly say?Everyone I met there had a reason and was on some kind of mission; promoting something or themselves, politicians, news people, activists specifically aligned & affiliated (or assororiated as the case may be) with this or that group ... Is that the way it has to be? You probably don't understand why I say this - Good from far, but far from good.

At least this delightful young woman didn't mind if I took her picture - and gave me a smile worth the price of admission. I guess that was the high point of the day. My feet began to hurt and I came back to this place that is not a home and forced myself to sleep.

I wanted to go up to the People's Assembly on Saturday - but there was Mister Gout again, barring the door. Oh well.

Luke, chapter 3 verse 10ff:

And the people asked him, saying, What shall we do then? He answereth and saith unto them, He that hath two coats, let him impart to him that hath none; and he that hath meat, let him do likewise. Then came also publicans to be baptized, and said unto him, Master, what shall we do? And he said unto them, Exact no more than that which is appointed you. And the soldiers likewise demanded of him, saying, And what shall we do? And he said unto them, Do violence to no man, neither accuse any falsely; and be content with your wages.This is John the Baptist doing the answering here; John the son of an old man and a barren woman, Zacharias & Elisabeth ... still, this is what comes to my mind this Easter Sunday morning - What shall we do then?

It ended badly for John the Baptist, Mark, chapter 6 verse 16ff:

... and the king was exceeding sorry ...Herod that is ... but that's another story.

Pachamama ... if it was 'Paschamama' you could invent an Easter connection eh?

Pachamama ... if it was 'Paschamama' you could invent an Easter connection eh?

Our Oxum is pictured on Rio Guaíba (aka the part of Rio Jacuí between Triunfo and the delta) which runs through Porto Alegre in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, then into the Baia de Guaíba and Lagoa dos Patos which finally meets the Atlantic Ocean down at Rio Grande and São José do Norte - which is where I took that picture of Não sou de Ninguém. Small world! Here's a view of the whole area.

Our Oxum is pictured on Rio Guaíba (aka the part of Rio Jacuí between Triunfo and the delta) which runs through Porto Alegre in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, then into the Baia de Guaíba and Lagoa dos Patos which finally meets the Atlantic Ocean down at Rio Grande and São José do Norte - which is where I took that picture of Não sou de Ninguém. Small world! Here's a view of the whole area. This statue of Iemanjá is at Mar Grosso, a few miles east of where the Guaíba water meets the sea; not marked but straight towards the ocean from São José do Norte on this map. It was late January so the young lad is up there decorating for the upcoming Nossa Senhora dos Navegantes celebration on the day of Iemanjá, February 2.

This statue of Iemanjá is at Mar Grosso, a few miles east of where the Guaíba water meets the sea; not marked but straight towards the ocean from São José do Norte on this map. It was late January so the young lad is up there decorating for the upcoming Nossa Senhora dos Navegantes celebration on the day of Iemanjá, February 2.Damned Papists hijacked Iemanjá's day for their own purposes! They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery though eh?

Where do you live? In the spirit? Hardly possible these days, but ok then, does your spirit still take flight and soar sometimes? And there is so much co-opting and put-on pretence and flat-out distortion that goes on, especially around anything like Iemanjá ... it's almost better to keep it private.

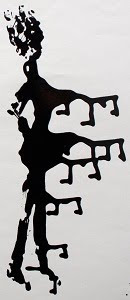

I'm not sure if she put the web of what looks like hooks and lines onto Pachamama intentionally, or if they are fortuitous drips (and I am afraid to ask); but her picture looks to me like Pachamama being dragged along, legs locked, in a web of manipulation to do some human bidding one way or another way.

So.

Credits: Meera Zavita Parmar - Pacha Mama, Naro Lokuruka at Push Creative Management, Zoom Br - Religiões Afro-Gaúchas.

Someone like Terry Jones or Wayne Sapp (the preachers who burned the Koran in Florida) might use the phrase 'daemonic parody' in an effort to incite you to join him (in his own personal hell); a social worker, or better, a manager of social workers, might be tempted to use it ... but wouldn't, quite; an NDP candidate (while wringing her hands) might use it referring to, say, Stephen Harper's government; I never heard Northrop Frye say it, so I don't really know what kind of baggage (if any) he attached to it; ...

I worship as well as I am able to, and if the gods and goddesses have all been painted over and repeatedly buggered ... well ... I worship what's left.

I mentioned Richard Peck a few weeks ago. At the time I sent a bunch of emails out with the question, "What is going on with Richard Peck deciding if Dziekanski's killers will be charged?" to various columnists & politicians.

I mentioned Richard Peck a few weeks ago. At the time I sent a bunch of emails out with the question, "What is going on with Richard Peck deciding if Dziekanski's killers will be charged?" to various columnists & politicians.Lo and behold! I got two answers: one from Neal Hall at the Vancouver Sun; and one from Vicky Huntington the independent MLA for the BC riding of Delta South - she defeated Wally Oppal, the BC Attorney General who decided not to charge the RCMP killers the first time round, by just a very few votes in 2009.

Of all the politicians in Canada, this woman (I believe) is not complacent. I just looked it up - she won by 2 votes! and on official recount it came to 32. No, she's not complacent. I would bet on it.

And Neal has now printed this: Mountie involved in fatal Dziekanski incident begins preliminary hearing today, Vanccouver Sun, April 18 2011.

So there is hope.

I mentioned before about having to go back and have another look at Ngũgĩ wa Thiongʼo because of this pesky Alzheimer's, so I am:

Wizard of the crow, 2006,And I decided I had better know a bit more about Mau Mau, so I got this: Mau Mau : an African crucible by Robert B. Edgerton, 1989, which I have been reading first.

Something torn and new : an African renaissance, 2009, and,

Dreams in a time of war : a childhood memoir, 2010.

Edgerton's remarkable assertion that circumcised women are capable of normal sexual relations (whatever 'normal' may turn out to be) and orgasms has two footnotes (see below): one from Jomo Kenyatta (apparently here, Facing Mount Kenya though it was not published in 1965 as indicated in the footnote), and one from hearsay 'assurances'.

I mentioned Kenyatta's defence of it before; now I will go back and re-read and possibly post the chapter. And I think there is a chapter in Dreams in a time of war which bears on it; maybe I will include that as well.

I admit - I obviously do not know what it is like to be a circumcised woman. My toenails go convex just thinking about it. But I do know enough anatomy - the clitoris is equivalent to the end of the penis (not the foreskin, the penis) - to seriously wonder ... This doesn't make tribal rituals inherently bad or evil either, but could we not at least start with facts rather than ideology and wishful thinking?

There was a blog entry and some videos on this subject at the Guardian this week.

More on this later maybe.

OK, here's a question.

Al Jazeera reports in Japan: Lives under pressure on April 12: "... a crowd of 12,000 gathered in Tokyo on Sunday to protest the country's nuclear policy, but that state TV did not cover the rally because they don't want to draw attention to the discord," with a video that leaves no doubt about the size of it.

Here's another report from Press TV (in Iran) Japanese protest Tokyo nuclear policy on April 10, the day of the demonstration: "About 15,000 Japanese people took to streets in different parts of Tokyo on Sunday, chanting 'No to nuclear bombs! No more Fukushima!'"

Here's another Al Jazeera report Japan nuclear debate on safety and energy and video from April 3 which suggests a clue.

It is easy to say, oh yeah, Al Jazeera and Press TV are shills; but the fact is that there have been numerous protests in Japan over nuclear energy since the earthquake and my question is this: Why is there not a single word about it ANYWHERE in the North American press?

That's it. No music. A little verse maybe: "One Ring to rule them all. One Ring to find them. One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them," that's what I say - Bah Humbug! No Easter hymn in here gawdammit!

Be well.

Postscript:

The politicians and their masters like big capital projects - nuclear power plants are perfect. The politicians and their masters don't like small distributed projects (like wind and solar) because they don't get a big enough cut.

As my friend Rolf used to say (in a fake German accent, though Rolf really was German), "Cooperation iss goot ... but control iss bettah!"

Why the politicians and their masters are not gung ho for large scale geo-thermal & solar-thermal is beyond me. Maybe they just haven't figgured it out yet? Maybe there's a problem with the vig. Dunno.

Oh, and if you happen to wonder about what will happen to the heroes and heroines who come forward for whatever reason to clean up the mess, say, 25 years down the road, check this out: Thousands protest benefits cuts for Chernobyl cleanup workers. You can Google around and find out that this pension is a princely $200 per month (month!).

Oh, and if you happen to wonder about what will happen to the heroes and heroines who come forward for whatever reason to clean up the mess, say, 25 years down the road, check this out: Thousands protest benefits cuts for Chernobyl cleanup workers. You can Google around and find out that this pension is a princely $200 per month (month!). And here's a video with prefix advert or without (but probably still with the adverts that 'No Evil' shoves in there).

And here's a video with prefix advert or without (but probably still with the adverts that 'No Evil' shoves in there).The 1.6 or 1.8 (call it 2) ... the TWO BILLION $ they will spend to refit the Chernobyl sarcophagus is in the bag though - well, if this ain't a parody, at least its daemonic.

Turns out it's 3,400 hectares (8,500 acres) and growing - everytime I see a number it is bigger. Here's a report in the Star, and here's a better map, and here's the guy himself, John Lowndes (who apparently doesn't like to be photographed) and his sidekick Michael Daniher. The American connection, The Baupost Group, keeps a website (which is totally locked and secured).

Turns out it's 3,400 hectares (8,500 acres) and growing - everytime I see a number it is bigger. Here's a report in the Star, and here's a better map, and here's the guy himself, John Lowndes (who apparently doesn't like to be photographed) and his sidekick Michael Daniher. The American connection, The Baupost Group, keeps a website (which is totally locked and secured).So then I went fossicking around Baupost, wondering what Seth Klarman might look like ... and found this: Seth Klarman Buys Land Worth $120 Billion for $80 Million!

That's what I call a BARGOON!

It seems that Baupost started out as an investment vehicle for "four families", see here, four very rich families one assumes ... according to Wikipedia Seth Klarman who runs it, does the things that investment wizards do: complex derivatives, put options ... these terms have a vaguely rotten smell since 2008 but who can say? all very legal no doubt ... and he's a philantropist, he gives some of it away, Cornell got 5 million. He and his wife have a foundation, The Seth A. and Beth S. Klarman Foundation, with a website, which, like The Baupost Group site noted above, says very little ... whatever.

It seems that Baupost started out as an investment vehicle for "four families", see here, four very rich families one assumes ... according to Wikipedia Seth Klarman who runs it, does the things that investment wizards do: complex derivatives, put options ... these terms have a vaguely rotten smell since 2008 but who can say? all very legal no doubt ... and he's a philantropist, he gives some of it away, Cornell got 5 million. He and his wife have a foundation, The Seth A. and Beth S. Klarman Foundation, with a website, which, like The Baupost Group site noted above, says very little ... whatever.So, for 80 million he gets to mess with three separate watersheds, AND support Canadian politicians when they decide to build roads at election time (it's the jobs y'unnerstan) AND make lots of cement AND take a big bite out of Ontario's hinterland (and that includes the people who live there too eh) AND make truckfulls of money. Hell, John Lowndes is merely a convenient tool for this fellow, a Canadian instrument.

Appendices:

1. Mountie involved in fatal Dziekanski incident begins preliminary hearing today, Neal Hall, April 18 2011.

2. Mau Mau - An African Crucible, Robert Edgerton, 1989, excerpt p. 40-41.

3. Mau Mau - An African Crucible, Robert Edgerton, 1989, excerpt p. 236-49.

4. Thousands protest benefits cuts for Chernobyl cleanup workers, April 17 2011.

5. U.S.-backed company proposes mega-quarry north of Orangeville, John Goddard, April 24 2011.

6. Seth Klarman Buys Land Worth $120 Billion for $80 Million!, Jacob Wolinsky, April 24 2011.

Mountie involved in fatal Dziekanski incident begins preliminary hearing today, Neal Hall, April 18 2011.

METRO VANCOUVER - An officer involved in the 2007 death of Robert Dziekanski at Vancouver's airport begins his preliminary hearing today in Surrey provincial court.

Cpl. Benjamin (Monty) Robinson, 41, is accused of obstruction of justice after being involved in a 2008 accident in Delta that killed motorcyclist Orion Hutchinson, 21.

The preliminary inquiry is being held to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to order Robinson to stand trial. It is set for four days, ending Thursday.

Hutchinson was killed the night of Oct. 25, 2008, when his motorcycle was struck by a Jeep driven by Robinson, who was off duty at the time.

Robinson said he was coming from a party earlier in the day, where he had had two beers. After the accident, he claimed he walked to his nearby home and had a couple shots of vodka, then returned to the scene of the accident.

He was then arrested and gave two breathalyser samples at 11:56 p.m. and 12:16 a.m. He blew .12 and .10, over the legal limit of .08. Delta police had recommended a charge of impaired driving but the Crown decided there was insufficient evidence. Robinson was charged with obstruction of justice. A coroner's investigation found that the accident victim also had been drinking alcohol, was over the legal limit and was travelling between 66 and 96 km/h. The investigation estimated that Robinson was not speeding.

Robinson was the senior officer on duty when Dziekanksi, 40, died at Vancouver's airport after he was repeatedly shot with an electronic stun gun on Oct. 14, 2007.

Thomas Braidwood, the retired judge who headed a public inquiry into tragedy, found the four officers mishandled the situation by approaching Dziekanski as though they were dealing with a pub brawl instead of a distraught and exhausted visitor, who had spent more than 10 hours in the airport after arriving from Poland.

The Polish man had come to Canada to live with his mother. He spoke no English and was unable to find his mother at the airport. Seconds after he was confronted by Robinson and three other Mounties, one of the officers repeatedly shocked Dziekanski with a Taser, even after he fell to the floor writhing in pain.

Dziekanski died after police handcuffed his hands behind his back. The Braidwood inquiry decided last June that the four officers displayed "shameful conduct" and were not justified using the Taser. The incident prompted an international outcry after a citizen's cell phone video of the officers' actions was posted on the Internet. The Crown decided there was insufficient evidence to warrant any charges being laid against Robinson and his fellow officers: Constables Kwesi Millington, Bill Bentley and Gerry Rundel.

Two weeks after Braidwood released his bluntly worded report, however, B.C.'s attorney general announced a special prosecutor was being appointed to have a second look at charges against the four Mounties.

The special prosecutor, Richard Peck, decided last June 29 that there was sufficient reason to re-consider whether the four officers should be charged. Peck still hasn't delivered his final decision, 10 months later.

Mau Mau - An African Crucible, Robert Edgerton, 1989, excerpt p. 40-41.

Another deep rift in Kikuyu society was created by missionaries from the African Inland Mission (AIM) who first opened their doors to converts in Kikuyuland in 1903. Initially, many Kikuyu sought out the missionaries in search of Western education or personal advantage; later they hoped that the missionaries would protect them against the tyranny of the chiefs. Soon a division emerged between the Christian converts and other Kikuyu, often including members of their own families, who continued to maintain traditional religious beliefs and practices.

An even more serious rift took place in 1929, when AIM and its African converts attempted to prohibit the traditional Kikuyu practice of circumcising girls prior to marriage. For reasons that remain obscure, the church did not object to the Kikuyu practice of circumcising teen-aged boys, but it regarded the circumcision of adolescent girls as barbaric. The Kikuyu, like many other African societies, made female circumcision a prerequisite for marriage and for full participation in the traditional world of women. From time to time, groups of girls were circumcised in a traditional ceremony which included the surgical removal of the tip of each girl's clitoris and some portions of her labia minora. The operation, which was performed without anesthetic by old women whose knives would never be mistaken for surgeons' scalpels, was terribly painful, yet most girls bore it bravely and few suffered serious infection or injury as a result.21 Circumcised women did not lose their ability to enjoy sexual relations, nor was their child-bearing capacity diminished.22 Nevertheless, the practice offended Christian sensibilities.

Many Kikuyu members of the AIM, left the church in protest against its anti-circumcision policy; they were known as aregi, while those who supported the policy were known as kirore. The two groups hurled insults at one another and there was violence. The aregi formed a new Christian church with its own schools, which later became known as Kikuyu Independent Schools, while the kirore remained within the AIM. Antagonism between the two groups grew worse over the I ensuing years and when the Mau Mau rebellion broke out, the aregi largely joined its ranks, while the kirore remained loyal to the British: government and fought against the Mau Mau.

Notes:

21 Kenyatta (1965).

22. Kikuyu men and women, like those of several other East African societies that practice female circumcision, assured me in 1961-62 that circumcised women continue to be orgasmic.

Bibliography:

Kenyatta, J. Facing Mt. Kenya: The Tribal Life of the Gikuyu. 2d ed. Introduction by B. Malinowski. New York: Vintage, 1962.

---------. Suffering Without Bitterness: The Founding of the Kenya Nation. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1968.

Facing Mount Kenya; the traditional life of the Gikuyu, Jomo Kenyatta, 1938.

Mau Mau - An African Crucible, Robert Edgerton, 1989, excerpt p. 236-49.

"Their Fierce Self-Interest"

Mau Mau in Perspective

The rebellion of the Land and Freedom Army did not achieve its goals. When the fighting ended in 1956, white settlers still owned their farms in the highlands, and white Colonial administrators still ruled Kenya. The leaders of Mau Mau had hoped that their rebellion would become an irresistible force for freedom spreading throughout Kenya. Not only did it not unite the African peoples of Kenya, it even failed to unite the Kikuyu. Instead, it led Kenya's largest tribe into a bitter and bloody civil war. By 1956, most of Kenya's Africans had repudiated Mau Mau. The rebellion was over, its goals unmet, it legacy uncertain.

Nevertheless, even though the leaders of Mau Mau did not realize it, their rebellion inadvertently brought about one vitally important change in Kenya. Before the rebellion, Kenya's white settlers were determined to achieve a form of self-rule that would assure their continuing control. Once the Mau Mau rebels forced the settlers to call for British military support, the political dominion of whites in Kenya was over. It was obvious to everyone except the least intelligent and most intransigent settlers that Kenya's future would be decided by Britain. The British Government poured enormous resources into Kenya to defeat Mau Mau, but by 1954 the cost of intervention had become such a heavy burden that if the rebellion had not ended when it did, Britain would have had difficulty continuing its military commitment in Kenya much longer. In fact, by 1956 British economic and military power had declined so much that Britain had to accept the humiliation of an American-imposed retreat from its invasion of the Suez Canal Zone. At the same time, Britain's African Colonies had become serious economic liabilities, and as European and American pressure to decolonize intensified, they became a political embarrassment as well. It was obvious that Britain could no longer afford the cost of holding Kenya by military might.

Yet only a few whites in Kenya seem to have understood that the end of colonialism in Africa was approaching, and only a few began to work toward the goal of economic reform buttressed by some form of a multi-racial government. If the white settlers had seized this opportunity to enhance economic and social justice, they might yet have assured a place for themselves as full partners in Kenya's future. But most would have nothing to do with reforms or African participation in government. They insisted on their economic privileges, their political power, and their racial superiority. In the fullness of their victory over Mau Mau, they overestimated their strength, and they badly misread the course of world events. "Their fierce self-interest," as Churchill had noted 50 years earlier, would bring about their final ruin.

The settlers' ruthless pursuit of their interests during the rebellion not only embittered the supporters of Mau Mau, it helped to radicalize educated young Africans as well. The white Kenyans' implacable refusal to share Kenya's future with the country's African population turned even many loyalist Africans against them just as it weakened their support in Britain. Only a few years after the fighting had ended, world developments having little to do with Kenya itself would persuade Harold Macmillan to grant independence to Britain's East African territories. But one critical event did involve Kenya, and it was a direct result of the settlers' excessive use of force against the Mau Mau. That event was the massacre at Hola. For many in Britain, Hola symbolized white Kenya's lawlessness. But for Macmillan and Macleod, Hola was more than a symbol; it was a bloody reminder that white minority government could only continue in Kenya by the use of deadly force. The unlimited use of force by the white settlers and the colonial administration had given them victory over the Mau Mau rebellion, but in the end it lost them Kenya. They had only themselves to blame.

In fairness, the white settlers cannot be held responsible for everything that led to Mau Mau. The gulf between prosperous land-owning Kikuyu and their poor, landless tenants existed before the whites arrived, and the settlers were not responsible for the disease and famine that had depopulated the highlands before they arrived. Nonetheless, the Government of Kenya had appropriated vast tracts of African land and urged whites to settle on it. When the settlers demanded more power and extended privileges, the colonial administration chose to accommodate them instead of protecting the interests of Kenya's Africans. Even when administrative officials attempted to assist Africans with various medical, livestock, and agricultural programs, their paternalistic arrogance in forcing these measures upon reluctant and uncomprehending tribal people alienated the very people they intended to help. So did government favoritism of chiefs and other wealthy supporters of the administration. What is more, colonial administrators allowed African grievances to reach a flashpoint by ignoring the needs of the rapidly growing numbers of urban poor, and by refusing to permit emerging African leaders to play a meaningful part in Kenya's political life.

Whatever the failings of the colonial administration, accountability for the genesis of Mau Mau nonetheless falls primarily on the settlers. Although the white community in Kenya had varied interests that, to take one example, sometimes brought cattle ranchers into conflict with farmers, in general they were united in exploiting African labor for the lowest possible wages, and united too in denying Africans the opportunity to compete with them as farmers or stockmen. They also shared the belief that Africans were inferior, childlike beings who should be denied social equality, not to mention self-government. As a result of the settlers' racism and their demands for profit, they consistently ignored the welfare of Africans who grew poorer and more aggrieved whether they lived in reserves, labored on European lands, or gathered in the towns and cities searching for work. When African protest movements arose, the settlers demanded that the government smash them. The settlers professed to understand Africans and insisted that they were bringing the benefits of British civilization to them, but these claims were sanctimonious. What they understood was their own narrow self-interest; what they gave to Kenya's African populations was continuing social inferiority and economic exploition. Most significant of all in accounting for the origin of Mau Mau, the white community made it absolutely clear to Kenya's Africans that future would bring no fundamental change.

The attitudes and practices of Kenya's whites were neither pathogical nor an aberration brought about by conditions unique to Kenya, as some have argued. They had deep roots in British culture and history. For one thing, British society was founded on the belief that some men were much more equal than others. The well-known bit of doggerel, "God bless the squire and his relations, and keep us in our proper stations," may have been partly derisive, but class distinctions were not merely remembrances of the nineteenth century for Kenya's whites — indeed, these distinctions gave legitimacy to white rule in Kenya. Even though the Labour Party had some success in challenging the authority of Britain's ruling class, few Britons in the 1950s disputed the idea that white people were superior to Africans. They were not unique. That black people were inferior to those of other races was taken for granted in much of Europe, Latin America, China, and Japan, as well as in the United States, which professed the equality of all yet maintained a color bar similar to the one in Kenya. It hardly needs saying that this belief is still widely-shared in many parts of the world.

White Kenyans' antipathy for Kenya's Africans was not only based on ideas of racial superiority, it was also a product of fear. Kenya's whites feared black Africans as much as white Americans in the antebellum South feared their slaves when they began to grow in number. Even though whites outnumbered blacks in the South, these Americans established a virtual police state for self-protection. In Kenya, 40,000 whites were surrounded by perhaps 6 million Africans whom white Kenyans believed were only a few years removed from bestial savagery. In such circumstances, it is not surprising that the white settlers failed to transcend their own racism as well as that of much of the developed world by working for a multi-racial society in Kenya. Yet the fact remains that the degrading racial policies they institutionalized went well beyond measures necessary for self-protection.

There can be no doubt that the settlers' racist attitudes and practices contributed to the outbreak of Mau Mau, but so did the settlers' uncompromising determination to rule Africans. Like many other Europeans who colonized Africa, Kenya's white settlers were convinced that it was not their superior weapons but their "superior civilization" that gave them an indisputable right to rule. Bolstered by their deep-seated belief in the principle that a small elite class could rightfully dominate a majority, white Kenyans from modest middle-class backgrounds eagerly joined settlers from Britain's "ruling class" in governing Kenya's Africans. Supported by the ruling-class ideology of the colonial administrators, white dominion became so deeply ingrained in the culture of Kenya's whites that even the kindest and most thoughtful of them were held in its thrall. White Kenyans understood that they could survive only as long as their economic symbiosis with Africans continued, but they chose to ensure that continuity, not by compromise or even understanding, but simply by the use of force. There were few voices of protest. Theirs was a society that left little room for dissent, and when the violence of Mau Mau struck, there was virtually no dissent at all. White Kenya was a society of masters — of "bwanas" and "memsahibs" — and, like masters throughout history who were threatened by rebellion, they closed ranks and responded ferociously.

When Mau Mau intimidation, arson, and violence first began, the settlers urged Draconian measures. When violence continued despite the government's declaration of a State of Emergency, the settlers took the destruction of the Mau Mau menace — and also took the law — into their own hands. Not all white men and women demanded the deaths of the "Kyukes," not all white Kenyans shot suspicious Kikuyu first and asked questions later, and not all whites in the Kenya Regiment or the Kenya Police Reserve tortured or murdered Mau Mau suspects. But many white Kenyans did all of these things, and those few who privately deplored what their friends and neighbors did rarely spoke out against them. Even the most liberal became entrapped in the convulsion of rage and revenge that engulfed the white community. The vicious reaction that swept through white Kenya grew in intensity as one example of brutality by whites was followed by another. White mothers whose children were cared for by Kikuyu women called for the execution of the inhabitants of entire Kikuyu "villages." Men who as children had played with young Kikuyu, and who later employed Kikuyu as servants and laborers, now thought of them as animals to be hunted, or vermin to be exterminated, while otherwise quite respectable white settlers became torturers and murderers.

The severity of the white reaction was heightened by the earliest Mau Mau killings. The first white victims, women as well as men, were chopped and slashed to death with pangas and swords. Their mutilated bodies were terrible to see or even hear about. When six-year-old Michael Ruck was killed by a flurry of panga blows, most settlers were convinced that the Mau Mau rebels were inhuman savages. Their rage was also intensified by a profound fear that African savagery, if not repressed, would engulf them all. The settlers were convinced that Africans were "primitives" whose "savage" impulses had been unleashed by the Mau Mau oaths. At best, they said, Africans were not fully human, and the Mau Mau rebels were clearly not the best of Africans. The feelings of a 31-year-old settler who had been born in Kenya were widely shared: "I was raised with Africans, you know. Kyukes mostly. I thought I knew what they were like but when the Mau Mau terrorism began I realized I didn't know them at all. They weren't like us. They weren't even like animals — animals are understandable. They're natural. The Mau Mau were ... what's the word? Perverted, I guess. It was the oath, you see. Once they took it, life didn't mean anything to them. If we couldn't drive the (Mau Mau) poison out of them by getting them to confess, all we could do was kill them." Settlers like this one killed Mau Mau suspects in an attempt to save all that was dear to them, and to destroy all that they did not understand. Most of them killed because they believed they had no other choice.

The settlers loved Kenya's beauty, its excitement, its comfortable and privileged way of life. As they saw it, Africans had done nothing to "develop" Kenya, and as a result they deserved their roles as servants and laborers for white men and women who had brought "civilization" to them. The Mau Mau rebellion was not only a direct threat to the lives of these white Kenyans, it was an affront to their sense of the natural order of things. If the challenge to white supremacy had come from a respected "fighting" people like the Somali or Massai, these settlers would still have insisted that the rebellion be crushed. But an uprising by "warriors" might at least have been understandable. Warlike peoples were expected to fight, and while they would have had to be killed, it would have been with some regret. The Kikuyu-led Mau Mau were thought of as cowards with no military tradition who had long been the subservient employees of whites. Many settlers thought of them as little more than slaves, and for people like these to repudiate white civilization and challenge white rule was galling.

For many settlers, Mau Mau was a modem-day equivalent of a slave uprising, and like white slave masters throughout history, they exacted terrible vengeance. White Kenyans had always feared the disastrous potential of a violent uprising by some or all of Kenya's millions of Africans, but they usually masked their underlying fear with exaggerated assurances that Africans were loyal, docile, and — most comforting of all — cowardly. They reassured themselves that their African servants and farm workers, would not — could not — have the temerity to harm white people. When this carefully crafted illusion of trust and security was shattered, the settlers felt betrayed and violated. As slave holders had done for centuries, they fought back for their pride, power, and privilege, as well as for their lives. And like the slave owners of history, their reaction was more violent than the actions of the Mau Mau rebels, and far more cruel. It must be remembered that, whenever African slaves rebelled in the New World, they were not only killed in large numbers, they were tortured and mutilated to demonstrate futility of insurrection.

C.L.R. James, who taught Kenyatta about political history in London, wrote that "The cruelties of property and privilege are always more ferocious than the revenges of poverty and oppression." Kenya's experience confirmed James' formulation. The whites were not content simply to kill the rebels, they insisted on teaching them an unforgettable lesson. The white Kenyans killed in the passion of the moment, as did the rebels, but unlike the Mau Mau, the whites routinely killed in cold blood, and they methodically tortured helpless captives. Many settlers believed that in order to teach Africans that whites would always be supreme, many more than 11,000 Kikuyu should have been killed. Three years before the Mau Mau rebellion erupted, tribal people on the island nation of Madagascar off Africa's east coast rose against French rule. While the world press paid virtually no attention, the French Army, aided by enraged French colonists, put down the rebellion with the same brutality that they would soon display in Algeria. When the French torture-chambers closed and thd killing stopped, somewhere between 50,000 and 120,000 Malagasy were dead. When news of the French slaughter reached Kenya, many settlers approved.

The settlers often attempted to justify their brutality by referring tat the rebels as "niggers," "baboons," "vermin," and the like. White ruthlessness certainly was inflamed by racist bigotry, but their cruelty had as much to do with "property and privilege" as racism. Although human savagery has often been motivated by racial hatred, many of history's most ghastly atrocities have had nothing to do with race, Racial hatred played a part in the white reaction to Mau Mau just as it did in the actions of many Mau Mau rebels, but the rebellion was fundamentally about power, not race, as the killing between the Kikuyu loyalists and the rebels demonstrated.

Whites were determined never to relinquish power, and many white men and women who considered themselves to be decent, fair-minded, and law-abiding used any means, however indecent, unfair,' and unlawful, to defeat the Mau Mau, without thinking any less of themselves. They knew that the acts they carried out or condoned were unlawful, and they conspired with one another to conceal what they did, but few admitted that their actions were morally wrong, and when they were accused of wrongdoing they were quick to justify themselves. It is tempting to think of the cruelty of their reaction to Mau Mau as a temporary outburst of hysteria, but, after the rebellion came to an end in 1956, few white Kenyans voiced any remorse. Even after the killings at Hola in 1959, very few expressed regret about what had happened there or elsewhere during the Emergency. Instead, they continued to insist that the Mau Mau had been a scourge so terrible that anything that had been done to destroy it was morally justified.

Even after 1956, when the Mau Mau rebellion had suffered military defeat and it was clear that Britain would require that some form of multi-racial government be established in Kenya, most settlers still showed little sympathy or concern for the interests of Africans, including those who worked on their own farms. They continued to neglect Africans' needs, degrade them by the same words and deeds that had so offended them before the rebellion began, and opposed attempts to improve race relations. When a liberal settler offered his highlands farm to the government as an inter-racial boarding school, his offer was rejected by the Minister of Education on the grounds that "no community" in Kenya would accept the idea. He meant, of course, no white community. Frustrated by this kind of intransigence, Governor Baring wrote to the Colonial Office about the settlers, saying that "There is a block of die-hards who cannot and will not be reconciled. Their fear and hatred of the African cannot be removed by any reasonable argument."

Baring neglected to say that there were those in the colonial administration who also feared and hated Africans. These men had behaved brutally and had covered up the brutality of others in government. Other high-ranking officials believed that they were serving the interests of Britain or Kenya by ordering or condoning actions that were both callous and unlawful. Governor Baring himself was deeply implicated. Although Baring took both his Roman Catholicism and his personal honor very seriously, he was nevertheless directly involved in rigging the trial of Kenyatta and five other defendants, and he helped to cover up the murderous brutality of the screening teams. His policy of enforced labor was punitive and cruel, and, as a result of his support for so-called villagization, many Kikuyu, particularly elderly persons and children, died of disease and malnutrition. By intervening to dismiss murder charges against Home Guardsmen in an attempt to bolster the morale of the loyalists, he made it abundantly clear that defeating the Mau Mau was more important than either principle or law. Yet in one of colonialism's many contradictions, Baring also worked devotedly to bring economic reform and multi-racial government to Kenya. Like other colonial officials in other lands, he had done his duty by crushing the rebellion, but now that the fighting had ended his duty called for him to lead Kenya toward lasting peace and prosperity.

Baring was not the only high official who sacrificed principles to defeat Mau Mau. Other members of the government cynically supported policies that were unlawful and indecent, then lied to cover their tracks. What is more, there were men in the Colonial Office in London who knew that the Government of Kenya was condoning criminal violence in its fight against the Mau Mau. Two successive Colonial Secretaries expressed concern over the excessive violence of Kenya's settlers, and even demanded that Baring explain allegations of brutality; but both Oliver Lyttleton and Alan Lennox-Boyd defended the actions of Kenya's colonial administration in Parliament and they did not demand impartial investigations of alleged misconduct. They may not have liked what was happening in Kenya, but they chose not to have it exposed.

It would be unfair not to acknowledge that there were white men and women in Kenya who displayed admirable qualities throughout the rebellion. Some colonial officials never wavered in protecting rights of Africans, even though they had to oppose their superiors, police, and the settlers to do so. Until Baring had him replaced, Attorney-General John H. Whyatt unfailingly insisted that all security forces act within the law, and some judges upheld the law despite pressures and threats. There were officers in prisons and detention camps who were fair and compassionate, and some settlers opposed the indiscriminate use of brutality against Mau Mau suspects; a few even took the risk of doing so openly. There were also men in the Kenya Police and Kenya Regiment who openly deplored the brutality of their fellow Kenyans, and showed truly remarkable courage devotion as they repeatedly led small patrols into the forests. Some of these men were killed, and others were killed in return, but they did so in open combat, took prisoners when they could, and refused to allow the use of torture.

A great many settlers, women as well as men, showed great courage and fortitude in defending their homes and families. They fought for the country they loved and they fought bravely. But the fact remains that many whites in Kenya did commit atrocious acts and many others approved. What is more, they believed that what they did was not only necessary but right. Many who have fought in other brutal wars later developed self-doubts and feelings of guilt, and some repudiated their actions. If white Kenyans felt any guilt, it did not compel them to make public disavowals of what they did. Like the Americans who settled the West, these white settlers were tough, self-reliant people, and like those same Americans, they were ruthless in pursuit of their interests. In earlier times, such ruthlessness might have insured their continued survival and dominance, but the wind of political change that swept through Africa as the 1950s came to a close was far too strong.

The pressures that drove so many whites to lawlessness also imposed terrible stresses on the Kikuyu, and to a lesser extent on other Africans, especially the Embu and Meru. The ordeal of the Mau Mau was not confined to the forest-based combat units or the detention camps; it was felt throughout the cities, towns, and reserves. Except for chiefs, well-educated people, and devout Christians, for whom there was no choice, almost every individual Kikuyu had to decide whether to join the emerging rebellion by taking the Mau Mau oath, or remain loyal to the government. It was not an easy choice. In the beginning, there was an exhilarating emotional appeal to the rebellion, but there was fear too: fear of the government, fear of the whites' power, and fear of the unknown. Soon there was even greater fear of the oath-administrators who began to force people to swear allegiance to Mau Mau. Many who refused, or who later gave evidence to the police, were killed. Friends, families, and clans were soon divided as the commitments of rebels and loyalists hardened and led to more and more killing.

Once a State of Emergency was declared, life became even more perilous. In addition to the danger from armed rebels or the loyalist Home Guards, all Kikuyu were now suspect in the eyes of armed white settlers, police, and soldiers. A man could be shot on sight, a woman raped, a house burned, all without apparent reason or warning. If a man or woman were picked up as a suspect, the danger was so terrible that many prisoners were too frightened to speak. Some would be released, but many would be tortured, some killed, and others sent to prisons or detention camps. Everyone, even those who remained uncommitted to either side, lived in perpetual fear of sounds in the night. No one, not even children, could be sure that they would not be attacked by rebels, Home Guards, the Kenya Police, or armed white settlers because someone regarded them as an enemy, or mistook them for one. For these Africans, the fear of sudden death became an inescapable part of daily life.

The threat of sudden violence was only one of the ever-present horrors of life. Many worried about loved ones in the forests or in detention camps. While they waited for news of their sons or fathers or sisters, they were forced to build roads, dig ditches, construct new villages, and endure the spread of hunger and disease. Some loyalists suffered almost as much as Mau Mau sympathizers. Many were killed or wounded, saw their houses burned, their crops destroyed, and their livestock stolen.

The Kikuyu suffered most during Mau Mau, but they were not the only people in Kenya who were tormented by the rebellion. Kenyans in some remote parts of the country were little affected by Mau Mau, but other people like the Maasai, Luhya, Luo, and Kamba were torn by divided loyalties. Still others, such as the Kipsigis and Nandi, chose to cast their lot primarily with the government. These peoples, along with the Kamba, provided most of the men who served in the expanded Kenya Police and as detention camp guards. Animosities between peoples who supported the government during the Emergency and those who did not endured for many years after Independence, as they did in families and clans. In some respects, Kenya's Indian community was the least divided. Many Indians were sympathetic to the idea of African independence, but they knew that the leaders of Mau Mau, like many other Kenyans, were so hostile to them that their only choice was to support the government. Their greatest concern was whether their loyalty to a government that treated them as second-class citizens would be appreciated. It was not, and their place in the life of Kenya is still uncertain.

For most Kenyans, including those who actually benefitted through new employment or government aid, Mau Mau was a period of uncertainty and anxiety. For those most intimately involved with the conflict, the rebellion brought years of suffering. How the millions of people who were affected by the rebellion reacted to its pressures was as varied as the people themselves, but those Africans who had the closest connection to the ordeal reacted just as the whites did — with extremes of cruelty and courage. Many loyalists were corrupt, cruel, and cowardly, but so were some people who supported the Mau Mau, and some loyalists were as brave and steadfast to their cause as any of the rebels. It is impossible to do more than speculate about the motives of the vast numbers of people who were caught up in the horror of Mau Mau, but one thing seems obvious. Kenya's Africans were every bit as concerned about furthering their interests as the settlers were; but unlike the settlers, who knew where their interests lay, the interests of the majority of Africans could shift as rapidly as the fortunes of war. For most of them, principles like freedom and social justice were often secondary to economic survival, and to survive they continually had to assess the relative strengths of the Mau Mau rebels and the security forces. Many calculatingly changed loyalties more than once as they watched the balance of power oscillate. Many whites accused Africans of being opportunistic, and they were right. Most Africans knew full well that their lives depended on their ability to avoid being caught in the crossfire. They experienced the truth of the African proverb that when elephants fight, it is the grass that gets trampled.

Those who held power in colonial Kenya — the whites, the Indians, and the African elite — were the natural enemies of Mau Mau. Some wealthy and powerful Kikuyu, like the Koinange family, supported the rebellion, as did a few wealthy Indians, but they were exceptions. Mau Mau was primarily a rebellion by the poor and powerless. Unless most of the educated, wealthy, Christian government loyalists joined Mau Mau — something equivalent to Tsar Nicholas and the Russian nobility joining the Communist revolution — conflict between the poor and powerful was inevitable. As it happened, the earliest victims of Mau Mau violence were wealthy Kikuyu chiefs and headmen who opposed the movement.

The conduct of the men and women who fought for Mau Mau included acts of conspicuous courage and military skill, senseless savagery and cowardice, and self-serving exploitation of others. These extraordinary differences reflect a similar diversity in the commitment of individuals to the causes of "land and freedom." Some who took the oath made no more than a pretense of supporting Mau Mau, because they believed that the rebels might win and because it was dangerous to oppose them. They also hoped for rewards if and when the rebels won. It is likely that the majority of those who actually fought for Mau Mau did so because their friends, relatives, or spouses did, and their commitment was more to these people than to the cause itself. Many marginally-committed Mau Mau gave up when it became clear that the rebellion could not succeed, and although some of the rebels who fought to the end did so because they knew that capture would mean death, many who were captured were profoundly committed to the goals of Mau Mau, and were therefore able to resist "rehabilitation" despite extreme duress.

Whatever one may choose to conclude about the tactics and strategies of Mau Mau's leaders, the actual fighting was done by ordinary men and women. Some of these rebels fought with undeniable brutality. They mutilated animals, raped African women, killed innocent children and pregnant mothers, strangled old women, gouged the eyes out of living victims, and burned people alive. What is more, some of their oathing ceremonies were so ghastly that many participants were appalled. None of these facts should be glossed over. But many other rebels, almost certainly the majority, did not participate in the more extreme oath ceremonies, nor did they kill women and children or commit other brutal acts against their enemies.

It must be kept in mind that most of the rebels had little if any knowledge of European ideas about the kinds of violence that should be permissible in warfare. In traditional Kikuyu battles, older women, men, and boys were always killed; only young women and girls were spared to be taken away as captives. With this conception of combat as their cultural heritage, it is remarkable that the majority of Mau Mau rebels showed as much restraint as they did. On the whole, they followed the rules of combat as their leaders defined them. With the military odds so hopelessly against them, many fought bravely by any standard, and when they were tortured in prisons and detention camps, their steadfast resistance was truly heroic.

All of Kenya's peoples who were touched by Mau Mau showed courage, all made sacrifices and all suffered. Yet no faction, neither the rebels, nor the loyalists, nor the whites, should be glorified. They all behaved in ways that are as horrifying now as they were then, and they all fought for their own interests. The whites and the African loyalists fought to retain their privilege and power under British colonialism. The rebels of Mau Mau fought to improve their own lives, but their rebellion was also intended to end colonial rule and to benefit Africans throughout Kenya. If political freedom, economic opportunity, and social justice are laudable goals, then the rebels were laudable in ways that those who fought to defend the colonial regime were not.

Ironically, most of the men and women who actively supported the movement gained nothing from it, while even before the Emergency ended, the Kikuyu loyalists and other tribes that opposed Mau Mau improved their land-holdings and many acquired new acreage. It is true that the lands of the white settlers were eventually sold to Africans, but only a handful of Mau Mau veterans had the money to afford this new property. In fact, most of those who had owned land before the rebellion began had their land and livestock confiscated, never to be returned. With a very few exceptions, former Mau Mau rebels were also not able to find jobs in government or in business. Loyalists retained the government jobs they held before the rebellion began, and when new positions became available, they were filled by the educated children of loyalists, not by uneducated rebels. Indians still dominated retail business, and former Mau Mau were not even allowed to serve in the army or police. Instead, virtually all of the Africans in the K.A.R. and the Kenya Police were retained by Kenyatta's government. These were the same men who had killed and tortured Mau Mau suspects. A rebellion by poor Africans forced Britain to withdraw from Kenya, but the land they had hoped to share and the government they had hoped to lead was taken over by wealthy and educated Africans who had either not fought at all, or had fought against the rebellion. There was no revolution in Kenya as a result of Mau Mau, only the replacement of elite white rulers by another elite, this time black.

In Kenya today, Mau Mau is a fading memory, little taught in schools, seldom discussed by intellectuals, uncelebrated by monuments, holidays, or songs. Yet no one can be certain what Mau Mau's legacy may eventually prove to be. It may continue to recede into Kenya's past as a regrettable prelude to the nation's independence. But remembrances of the rebellion are very much alive for some Kenyans, and like many other historical events, Mau Mau may take on greater symbolic significance as time passes. That may already be happening: In 1987, a group of Kenyan exiles assembled in London on the thirtieth anniversary of Dedan Kimathi's execution to announce the formation of a movement dedicated to the overthrow of Kenya's Government. Calling themselves "Ukenya" — Movement for Unity and Democracy in Kenya — the leaders of the movement evoked the memory of Kimathi's strength in demanding that the Kenya Government end political detention, equalize wealth, restore democracy and, once again, return the "lost" lands to the people. In August 1988, Jomo Kenyatta's nephew, Andrew Kibathi Muigai, was sent to jail for six years for belonging to Ukenya's underground organization in Kenya.

Thousands protest benefits cuts for Chernobyl cleanup workers, April 17 2011.

KIEV, UKRAINE—About 2,000 veterans of the Chernobyl cleanup operation have rallied in Ukraine’s capital to protest cuts in benefits and pensions.

Sunday’s protest in Kyiv comes just days ahead of the 25th anniversary of the explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, as international attention is once again focused on the disaster that sent clouds of radiation over much of Europe.

Protesters expressed their anger at the government over drastically reduced pensions and the rising cost of health care, with more cutbacks to come.

President Viktor Yanukovych’s government says it simply does not have the money to meet promises made to the tens of thousands of workers who were sent in to clean up the radioactive site after the nuclear explosion on April 26, 1986.

U.S.-backed company proposes mega-quarry north of Orangeville, John Goddard, April 24 2011.

An American-backed company that assembled farmland north of Orangeville to grow potatoes has applied to develop one of Canada’s biggest rock quarries.

But neighbouring farmers are warning of environmental and community consequences if it’s allowed to proceed.

The Highland Companies, backed by Boston-based hedge fund Baupost Group, proposes to dig what it calls a “mega-quarry” from a top-quality limestone deposit just north of Shelburne in Melancthon Township.

The quarry lands are to stretch five kilometres across and plunge 200 feet down, farther than the Horseshoe Falls at Niagara. A “mega-quarry” is defined as having a rock reserve of at least 150 million tonnes. The Highland reserve has 1 billion tonnes, part of a 6-billion-tonne deposit.

People protesting the quarry held a rally at Queen’s Park on Friday and began a five-day walk 100 kilometres north to the quarry site. The deadline for written objections to the project is their arrival day, Tuesday.

“The (company) application runs more than 3,100 pages, and took five years and 20 consulting firms to create,” says area cattle rancher and horse trainer Carl Cosack, a rally participant. “The public was given 45 days to respond.”

The Highland Cos. first showed itself in Melancthon Township in 2006, in the form of John Lowndes and the name Headwater Farms.

Lowndes started buying properties at $8,000 an acre in a region that has long been poorly serviced and economically depressed. The price included “a significant premium over market value,” company spokesman Michael Daniher says.

Eventually, Lowndes assembled more than 3,400 hectares (8,500 acres), including the area’s two largest potato operations — Downey Potato Farms and Wilson Farms — turning Highland into Ontario’s biggest potato grower, packer and distributor. It produces 45.5 million kilograms (100 million pounds) a year.

Lowndes, an Orangeville civil engineer and entrepreneur now living in nearby Alton, continues as sole company director.

In assembling its lands, the company bulldozed 30 farmhouses, many dating to the 1800s, along with trees, bush lots, and modern storage and processing facilities, says rancher Cosack, who is also vice-chair of the citizens’ group North Dufferin Agricultural and Community Task Force (NDACT).

“Rural communities are fairly small,” Cosack says of the destruction of the area’s rural character. “When you start taking out houses where people used to live, people who go to church and go to the hockey arena and who volunteer places — that just got under the skin of a lot of people.”

When Highland started drilling for what it said were irrigation wells, Cosack says, people got suspicious and began to organize. Although Highland didn’t have to, Daniher says, it held a public meeting in 2009 laying out the proposal for a quarry occupying 940 hectares.

“Aggregates are one of the foundations of our modern society,” a company report says of materials used for everything from highway construction to skyscraper windows.

The quarry would be ideally situated, the report says, close to markets but outside the environmentally designated Greenbelt and Niagara Escarpment. The quarry would serve Ontario’s needs for decades, it says, with 90 per cent of the aggregate going to construction in the Greater Golden Horseshoe, and 10 per cent to Barrie.

Opponents, which include Citizens’ Alliance for a Sustainable Environment (CAUSE), question whether the markets will stay local.

Three years ago, Highlands agreed to buy a rail line between Orangeville and Mississauga, and it’s negotiating purchase of a rail right-of-way to the Great Lakes port of Owen Sound, spokesman Daniher confirms. Just as potatoes form one of Highland’s business interests, so do railways, he says. No foreign markets and no expansion of the proposed quarry are planned, he says.

Opponents raise truck traffic and water management as other areas of top concern.

Because the water table in Melancthon Township is high, Highland would have to pump 600 million litres of water a day from the quarry, equivalent to the volume used by 2.7 million Ontarians. Having to store the water for three days to reduce sediment means having to handle 1.8 billion litres of water per day, both sides agree. The technology exists to manage such volumes, the company says.

As for truck traffic, Highland’s application proposes to finance road improvements if its requirements exceed 150 40-tonne trucks per hour, 24 hours a day, every day except statutory holidays.

Opponents also express concerns about groundwater degradation and other environmental damage.

“If I had a two-acre lot and wanted to build a house (in Melancthon Township),” Cosack says, “I would need an environmental assessment.”

Under Ontario law, an environmental assessment is not required for a mega-quarry.

Seth Klarman Buys Land Worth $120 Billion for $80 Million!, Jacob Wolinsky, April 24 2011.

The title is not a typo!

I found some interesting things going on in Baupost from of all places an environmental group. When you look at Baupost’s 13-Fs you will notice that despite the company having $20 billion under management only about 5% is in domestic stock. Most of the questions where what is Klarman doing with the other $20 billion?

Half of the $20 billion is cash, so that leaves $9 billion that no one knows for sure where it is going. Klarman (my source tells me) owns a lot of foreign stocks and some Real Estate.

Klarman has been buying some expensive potato farms in Ontario, paying $8,000 an acre. It is clearly not a play on Potatoes (Only 1 year worth of demand left in the local reserves), but rather what can be done with the ground.

Here is the history according to http://www.inthehills.ca/back/melancthon/:

Baupost Group, a $14 billion, Boston-based hedge fund, headed by investment guru Seth Klarman. In partnership with Baupost, Lowndes founded Highland in 2006 to develop resources in Melancthon Township. Late that year, after extensive research, Lowndes approached a number of landowners, offering them $8,000 an acre, 30 per cent or so above market value. Lowndes hoped, he says modestly, to get 1,500 acres to run a profitable potato operation.

Lowndes purchased his first 25 acres in Melancthon in November 2006. Within six months he owned 4,400 acres; within a year, 6,500. Today, The Highland Companies owns 7,500 acres in Melancthon and additional lands in Mulmur Township and Norfolk County – 9,500 acres in all.

Now some more recent news from [www.avcanada.ca]:

The Highland Companies in Canada, owned by the Baupost Group Hedge Fund in Boston, have recently filed an application to dig what will be the largest open pit aggregates quarry in Canada right on top of the Niagara Escarpment! Just north of Shelburne, and south of Blue Mountain, Ontario they plan to mine an area that is almost 10 square kilometers to a depth 200 feet below the water table. This land is prime agricultural “Class A” soil situated at the highest point in southern Ontario. Three major watersheds have their headwaters here – the Saugeen, the Nottawasaga and the Grand Rivers – supplying fresh water to well over 1 million Ontario residents.

If successful the operation will run 24/7. Millions of tons of limestone will be extracted and sold for highway gravel or as lime for cement.

To date the companies have assembled 7000 acres (28 sq. km.) under the pretext of running the largest potato farm in Ontario.

According to HighLands website, the land contains over 6 billion tons of the highest qualities in reserve. Various types of institutions need the material, and demand in Ontario alone is close to 200 million tonnes a year, so Baupost would not have to do much shipping. The website states that the land is also valuable because it is right near a road (Road 124), there are minor environmental issues involved, it is surrounded by agriculture and wind farm, and there is no specialty planning zones.

However, environmental groups have claimed that the site of the proposed second largest quarry in North America is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

Costs are estimated to be $140 million a year. The cost of the land purchased is close to $80 million. Klarman is paying a hefty price, and besides the recent announcement about the opening of the quarry (which was only filed on March 7th 211) not much else has been said by Highlands. Klarman likely wants this land due to the supply/demand imbalance for aggregates (limestone). Lime price depends on a variety of factors that makes it tough to get an exact number here. However, assuming an average of $20 per tonne (this is probably low), Klarman paid $80 million for $120billion worth of resources! It will take decades to extract but assuming Baupost gets approval it is hard to see them not making a fortune off of this.

Highlands has filed an application with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources to obtain a license to excavate this prime agricultural land into the 2nd largest open mine pit in all of North America, to start quarrying on some of the land they own containing 1 billion tonnes of the lime.

There will be the yearly costs, and there are a lot of environmental groups fighting this. I do not see any mention of royalty costs; only that Baupost will pay $1.2m in taxes a year to the township.

However, this looks like a steal based on the fact that the resources are worth over 1,000 times the purchase price of the land. The court will decide very soon whether the quarry can be built (According to the Highland Companies website, April 26th is “the last day for public objections). Even if Klaman is not allowed to build, it is an absurd risk reward ratio in the equation.

There is no way for the retail investor to coattail this idea even if they want to. However, it will be interesting to see how this plays out, and how much money Klarman will make from it.

I have reached out to the leader of the main environmental group fighting this (http://www.ndact.com) for comment. I have also contacted Baupost, and Highland to hear if they are willing to comment on the issue.

I am hoping both sides will be willing to answer questions on the record.

Down

i love this blog!!!!

ReplyDelete