Up, Down, Appendices, Postscript.

No really good things came my way this week. Oh well; so it goes eh?

No really good things came my way this week. Oh well; so it goes eh?There were a few modest things, not quite 'good' but close maybe (sorry to prevaricate) ...

Steed Lord & wha'cha gonna do when the sky turns red and again here here here and here, and of course, a line of fashion & accessories to go along with it ... (thanks to Miss Jodie).

your time has come

a storm is coming

our storm

come on

I walk up in the club

I walk up in the clubI'm searchin' for my drugs

these days are way too long

I need to get some kind'a love

my eyes are locked on you

can you tell me the truth

I need to feel you touchin' me

its travelin' inside my mind

wha'cha gonna do when the sky turns red

wha'cha gonna do when the sky turns red

waiting for the sun that never sets

will you come'a closer take my hand

the day is drawing near

the moon is almost clear

why can't I face my fears

I want the wild lady to appear

I gotta go, let's go, wha'cha gonna do

wha'cha gonna do when the sky turns red

take my hand

A-and this from the CBC's Fifth Estate (on their exceedingly lame website): You Should Have Stayed At Home; including the Toronto G20 laid out time-wise and with an interview by Gillian Findlay with the Chief of Po-leece, Bill Blair (if you can bear the ads at double volume) ... or better, download it and bypass the over-loud advertisements and the lame CBC infrastructure entirely.

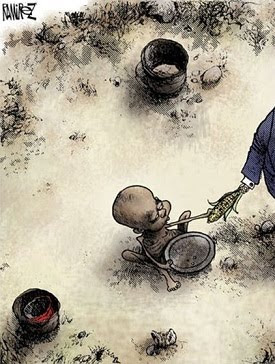

A-and this from the CBC's Fifth Estate (on their exceedingly lame website): You Should Have Stayed At Home; including the Toronto G20 laid out time-wise and with an interview by Gillian Findlay with the Chief of Po-leece, Bill Blair (if you can bear the ads at double volume) ... or better, download it and bypass the over-loud advertisements and the lame CBC infrastructure entirely.And this: Economic Hitmen (thanks to Greenspiration for 'You Should Have Stayed At Home' & 'Economic Hitmen').

Considering our Bill Blair there, between Svala Björgvinsdóttir & Gillian Findlay ... instead of 'a thorn between two roses' you could say a damp (mealy mouthed) squib between two blondes, but I'm not sure that any of them is a true blonde.

The Globe, citing a survey cooked up by realtors, says "House prices see annual gains of 6.8% over past 10 years," while in the Star it's "Housing prices to drop 25%, forecaster predicts." That's good-ish news I guess. The BBC reports "UK GDP figure revised down further," and "... the economy is still flattish at minus 0.1%." These are a few hopeful signs, but the people writing this bumph don't really have any idea.

... as for me ...

I got nothin’ to say, 'specially about, whatever it was ...

I got nothin’ to say, 'specially about, whatever it was ...Be well.

Postscript:

I have been following events in the middle east of course, but this Doonesbury ... well, after I looked at the Sunday funnies I decided to select the best of what I have seen and post it. I don't use TV but I think Garry Trudeau's representation is about right. And not only for TV either, the Internet is about the same, everyone screaming, "LOOK AT ME!"

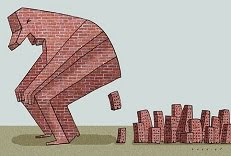

I have been following events in the middle east of course, but this Doonesbury ... well, after I looked at the Sunday funnies I decided to select the best of what I have seen and post it. I don't use TV but I think Garry Trudeau's representation is about right. And not only for TV either, the Internet is about the same, everyone screaming, "LOOK AT ME!"I am an elitist snob, so mob rule doesn't much appeal to me; nor the notion of government by polls or unending referendums. But the elites, like God during the Holocaust, have turned their backs on us and are pursuing only their own (and their immediate families') well being. They have turned wealth into illth & filth.

The first reports seemed to be all about portraying 'social media' as some kind of ... what? But the social media don't appeal to me either. So as I fossicked about the Internet dung heap I was looking for other reasons.

Gwynne Dyer has a cool head and his two pieces (presented out of time-sequence but in the order I found them) laid it out pretty clearly I thought:

Why now?, February 20, and,

Good sense of the Arabs, February 14.

I don't know a thing about Fouad Ajami beyond what is in this article: How the Arabs Turned Shame Into Liberty; and they have yet to turn anything into any 'liberty' I would recognize; but he sketches the history, and reveals himself maybe more than he intended, so I include him too.

I am especially leery of mobs which include religion and religious rites. I will spare you pictures of people holding up their shoes. Throwing one at W was a beautiful thing to behold, but I wonder how self-conscious a crowd is when they all hold their shoes up together for what looks like a photo op, sorry.

I am especially leery of mobs which include religion and religious rites. I will spare you pictures of people holding up their shoes. Throwing one at W was a beautiful thing to behold, but I wonder how self-conscious a crowd is when they all hold their shoes up together for what looks like a photo op, sorry.

My friend Crowbird used to go around cleaning things up, sometimes just to pass the time.

My friend Crowbird used to go around cleaning things up, sometimes just to pass the time.There are never as many to clean up as there were to make the mess. It is not entirely clear what is going on, but it looks like some people at least got right to work. That's the stuff.

Appendices:

1. Why now?, Gwynne Dyer, February 20 2011.

2. Good sense of the Arabs, Gwynne Dyer, February 14 2011.

3. How the Arabs Turned Shame Into Liberty, Fouad Ajami, February 26 2011.

Why now?, Gwynne Dyer, February 20 2011.

Why now? Why revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt this year, rather than last year, or 10 years ago, or never? The protestors now taking to the street daily in Jordan, Yemen, Bahrain, Libya and Algeria are obviously inspired by the success of those revolutions, but what got the process started? What changed in the Middle East?

Yes, of course the Arab world is largely ruled by autocratic regimes that suppress all opposition and dissent, sometimes with great cruelty. Yes, of course many of those regimes are corrupt, and some of them are effectively in the service of foreigners. Of course most Arabs are poor and getting poorer. But that has all been true for decades. It never led to upheavals before.

Maybe the frustration and resentment that have been building up for so long just needed a spark. Maybe the self-immolation of a single young man set Tunisia alight, and from there the flames spread quickly to half a dozen other Arab countries. But you can`t find anybody who really believes that this could just as easily have happened five years ago, or 10, or 20.

Yet there is no reason to suppose that the level of popular anger has gone up substantially in the past two or five or 10 years. It`s high all the time, but in normal times most people are very cautious about expressing it openly. You can get hurt that way.

Now they are expressing their anger very loudly indeed, and long-established Arab regimes are starting to panic. The fall of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, by far the largest Arab country, makes it possible that many other autocratic regimes in the Arab world could fall like dominoes. The rapid collapse of the communist regimes in Europe in 1989 is a frightening precedent for them. But, once again, why is this happening now?

`Social media` is one widely touted explanation, and the al-Jazeera network`s wall-to-wall coverage of the events in Tunisia and Egypt is another. Both are plausible parts of the explanation, for the availability of means of communication that are beyond the reach of state censorship clearly makes mass mobilisation much easier. If people are ready to come out on the street and protest, the media makes it easier for them to organise. But this really does not explain why they are ready to come out at last.

The one thing that is really different in the Middle East, just in the last year or two, is the self-evident fact that the United States is starting to withdraw from the region. From Lebanon in 1958 to Iraq in 2003, the US was willing to intervene militarily to defend Arab regimes it liked and overthrow those that it did not like. That`s over now.

This great change is partly driven by the thinly-disguised American defeat in Iraq. The last US troops are leaving that country this year, and after that grim experience US public opinion will not countenance another major American military intervention in the region. The safety net for Arab regimes allied to the United States is being removed, and their people know it.

There is also a major strategic reassessment going on in Washington, and it will almost certainly end by downgrading the importance of the Middle East in US policy. The Arab masses do not know that, but the regimes certainly do, and it undermines their confidence.

The traditional motives for American strategic involvement in the Middle East were oil and Israel. American oil supplies had to be protected, and the Cold War was a zero-sum game in which any regime that the US did not control was seen to be at risk of falling into the hands of the Soviet Union. And quite apart from sentimental considerations, Israel had to be protected because it was an important military asset.

But the Cold War is long over, and so is the zero-sum game in the Middle East.

Good sense of the Arabs, Gwynne Dyer, February 14 2011.

They wouldn't do it for al-Qaida, but they finally did it for themselves. The young Egyptian protesters who overthrew the Mubarak regime on Saturday have accomplished what two generations of violent Islamist revolutionaries could not. And they did not just do it nonviolently; they succeeded because they were nonviolent.

They also succeeded because they had reasonable goals that could attract mass support: democracy, economic growth, social justice. This was in marked contrast to the goals of the Islamist radicals, which were so unrealistic that they never managed to get the support of the Arab masses.

Even to talk about "the masses" sounds anachronistic these days, but when we are talking about revolution it is still a relevant category. Revolutions, whether Islamist or democratic, win if they can gain mass support, and fail if they cannot. The Islamists have got a great deal of attention in the past two decades, and especially since 9/11, but as revolutionaries they are spectacular failures.

The problem was their analysis of what was wrong in the Arab world. Like most extremist versions of religion, Islamism is a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Its diagnosis essentially says that the poverty, oppression and humiliation that Arabs experience are due to the fact that they are not obeying God's rules, especially about dress and behavior, and so God has turned His face from them.

The cure for all these ills, therefore, is precise and universal observance of all God's rules and injunctions, as interpreted in their peculiarly narrow and intolerant version of Islam. Men must grow their beards, for example, but they must not trim them. If only they get these and a thousand other details right, the Arabs will be rich, respected and victorious, for then God will be willing to help them.

The Islamists never talked about the Arabs, of course. They spoke only of "the Muslims," for their ideology rejected all distinctions of history, language and nationality: the ultimate objective was a unified "Caliphate" that erased all borders between Muslim countries. In practice, however, most of them were Arabs, although Arabs are only a quarter of the world's Muslims.

Osama bin Laden is a Saudi Arabian. His deputy, Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, is an Egyptian. The great majority of the founders of al-Qaida were Arabs. That makes sense, for it is the Arab world that has seen the greatest fall from former prosperity, lives under the worst dictatorships, and has suffered the greatest humiliations at the hands of the West and Israel.

From Turkey to Indonesia, most non-Arab Muslim countries enjoy reasonable economic growth, and some are full-blooded democracies. Their governments work on behalf of their own countries, not for Western interests, and they do not have to contend with an Israeli problem. If there was ever going to be mass support for the Islamist revolution, it was going to be in the Arab world.

Revolutionary movements often resort to terrorism: it's a cheap way of drawing attention to your ideas, and it may even lead to an uprising if the target regime responds by becoming even more oppressive. The first generation of Islamists thought they would trigger an uprising in Saudi Arabia when they seized control of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979, and in Egypt when they assassinated President Anwar Sadat in 1981.

There were no mass uprisings in support of the Islamists either then or later, however, and the reason is that Arabs aren't fools. Many of them intensely disliked the regimes they lived under, but it took only one look at the Islamist fanatics, with their straggly beards and counter-rotating eyeballs, to know that they would not be an improvement.

A second generation of Islamists, spearheaded by al-Qaida, pushed the strategy of making things worse to its logical conclusion. If driving Arab regimes into greater repression could not trigger pro-Islamist revolutions, maybe the masses could be radicalized by tricking the Americans into invading Muslim countries. That was the strategy behind the 9/11 attacks ― but still the masses would not come out in the streets.

When they finally did come out in the past couple of months, first in Tunisia, then in Egypt, and already in other Arab countries as well, it was not in support of the Islamist project at all. What the protesters were demanding was democracy and an end to corruption. Some of them may want a bigger presence for Islam in public life, and others may not, but very few of them want revolutionary Islamism.

It is a testimony to the good sense of the Arabs, and a rebuke to the ignorant rabble of Western pundits and "analysts" who insisted that Arabs could not do democracy at all, or could only be given it at the point of Western guns.

It is equally a rebuke to bin Laden and his Islamist companions, hidden in their various caves. They were never going to sweep to power across the Arab world, let alone the broader Muslim world, and only the most impressionable and excitable observers ever thought they would.

How the Arabs Turned Shame Into Liberty, Fouad Ajami, February 26 2011.

Perhaps this Arab Revolution of 2011 had a scent for the geography of grief and cruelty. It erupted in Tunisia, made its way eastward to Egypt, Yemen and Bahrain, then doubled back to Libya. In Tunisia and Egypt political freedom seems to have prevailed, with relative ease, amid popular joy. Back in Libya, the counterrevolution made its stand, and a despot bereft of mercy declared war against his own people.

In the calendar of Muammar el-Qaddafi’s republic of fear and terror, Sept. 1 marks the coming to power, in 1969, of the officers and conspirators who upended a feeble but tolerant monarchy. Another date, Feb. 17, will proclaim the birth of a new Libyan republic, a date when a hitherto frightened society shed its quiescence and sought to topple the tyranny of four decades. There is no middle ground here, no splitting of the difference. It is a fight to the finish in a tormented country. It is a reckoning as well, the purest yet, with the pathologies of the culture of tyranny that has nearly destroyed the world of the Arabs.

The crowd hadn’t been blameless, it has to be conceded. Over the decades, Arabs took the dictators’ bait, chanted their names and believed their promises. They averted their gazes from the great crimes. Out of malice or bigotry, that old “Arab street” — farewell to it, once and for all — had nothing to say about the terror inflicted on Shiites and Kurds in Iraq, for Saddam Hussein was beloved by the crowds, a pan-Arab hero, an enforcer of Sunni interests.

Nor did many Arabs take notice in 1978 when Imam Musa al-Sadr, the leader of the Shiites of Lebanon, disappeared while on a visit to Libya. In the lore of the Arabs, hospitality due a guest is a cardinal virtue of the culture, but the crime has gone unpunished. Colonel Qaddafi had money to throw around, and the scribes sang his praise.

Colonel Qaddafi had presented himself as the inheritor of the legendary Egyptian strongman Gamal Abdel Nasser. He had written, it was claimed, the three-volume Green Book, which by his lights held a solution for all the problems of governance, and servile Arab intellectuals indulged him, pretending that the collection of nonsensical dictums could be given serious reading.

***

To understand the present, we consider the past. The tumult in Arab politics began in the 1950s and the 1960s, when rulers rose and fell with regularity. They were struck down by assassins or defied by political forces that had their own sources of strength and belief. Monarchs were overthrown with relative ease as new men, from more humble social classes, rose to power through the military and through radical political parties.

By the 1980s, give or take a few years, in Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Libya, Algeria and Yemen, a new political creature had taken hold: repressive “national security states” with awesome means of control and terror. The new men were pitiless, they re-ordered the political world, they killed with abandon; a world of cruelty had settled upon the Arabs.

Average men and women made their accommodation with things, retreating into the privacy of their homes. In the public space, there was now the cult of the rulers, the unbounded power of Saddam Hussein and Muammar el-Qaddafi and Hafez al-Assad in Syria and Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia. The traditional restraints on power had been swept away, and no new social contract between ruler and ruled had emerged.

Fear was now the glue of politics, and in the more prosperous states (the ones with oil income) the ruler’s purse did its share in the consolidation of state terror. A huge Arab prison had been constructed, and a once-proud people had been reduced to submission. The prisoners hated their wardens and feared the guards, and on the surface of things, the autocracies were there to stay.

Yet, as they aged, the coup-makers and political plotters of yesteryear sprouted rapacious dynasties; they became “country owners,” as a distinguished liberal Egyptian scholar and diplomat once put it to me. These were Oriental courts without protocol and charm, the wives and the children of the rulers devouring all that could be had by way of riches and vanity.

Shame — a great, disciplining force in Arab life of old — quit Arab lands. In Tunisia, a hairdresser-turned-despot’s wife, Leila Ben Ali, now pronounced on all public matters; in Egypt the despot’s son, Gamal Mubarak, brazenly staked a claim to power over 80 million people; in Syria, Hafez al-Assad had pulled off a stunning feat, turning a once-rebellious republic into a monarchy in all but name and bequeathing it to one of his sons.

***

These rulers hadn’t descended from the sky. They had emerged out of the Arab world’s sins of omission and commission. Today’s rebellions are animated, above all, by a desire to be cleansed of the stain and the guilt of having given in to the despots for so long. Elias Canetti gave this phenomenon its timeless treatment in his 1960 book “Crowds and Power.” A crowd comes together, he reminded us, to expiate its guilt, to be done, in the presence of others, with old sins and failures.

There is no marker, no dividing line, that establishes with a precision when and why the Arab people grew weary of the dictators. To the extent that such tremendous ruptures can be pinned down, this rebellion was an inevitable response to the stagnation of the Arab economies. The so-called youth bulge made for a combustible background; a new generation with knowledge of the world beyond came into its own.

Then, too, the legends of Arab nationalism that had sustained two generations had expired. Younger men and women had wearied of the old obsession with Palestine. The revolution was waiting to happen, and one deed of despair in Tunisia, a street vendor who out of frustration set himself on fire, pushed the old order over the brink.

And so, in those big, public spaces in Tunis, Cairo and Manama, Bahrain, in the Libyan cities of Benghazi and Tobruk, millions of Arabs came together to bid farewell to an age of quiescence. They were done with the politics of fear and silence.

Every day and every gathering, broadcast to the world, offered its own memorable image. In Cairo, a girl of 6 or 7 rode her skateboard waving the flag of her country. In Tobruk, a young boy, atop the shoulders of a man most likely his father, held a placard and a message for Colonel Qaddafi: “Irhall, irhall, ya saffah.” (“Be gone, be gone, O butcher.”)

In this tumult, I was struck by the chasm between the incoherence of the rulers and the poise of the many who wanted the outside world to bear witness. A Libyan of early middle age, a professional and a diabetic, was proud to speak on camera, to show his face, in a discussion with CNN’s Anderson Cooper. He was a new man, he said, free of fear for the first time, and he beheld the future with confidence. The precision in his diction was a stark contrast to Colonel Qadaffi’s rambling TV address on Tuesday that blamed the “Arab media” for his ills and called on Libyans to “prepare to defend petrol.”

In the tyrant’s shadow, unknown to him and to the killers and cronies around him, a moral clarity had come to ordinary men and women. They were not worried that a secular tyranny would be replaced by a theocracy; the specter of an “Islamic emirate” invoked by the dictator did not paralyze or terrify them.

***

There is no overstating the importance of the fact that these Arab revolutions are the works of the Arabs themselves. No foreign gunboats were coming to the rescue, the cause of their emancipation would stand or fall on its own. Intuitively, these protesters understood that the rulers had been sly, that they had convinced the Western democracies that it was either the tyrants’ writ or the prospect of mayhem and chaos.

So now, emancipated from the prison, they will make their own world and commit their own errors. The closest historical analogy is the revolutions of 1848, the Springtime of the People in Europe. That revolution erupted in France, then hit the Italian states and German principalities, and eventually reached the remote outposts of the Austrian empire. Some 50 local and national uprisings, all in the name of liberty.

Massimo d’Azeglio, a Piedmontese aristocrat who was energized by the spirit of those times, wrote what for me are the most arresting words about liberty’s promise and its perils: “The gift of liberty is like that of a horse, handsome, strong and high-spirited. In some it arouses a wish to ride; in many others, on the contrary, it increases the urge to walk.” For decades, Arabs walked and cowered in fear. Now they seem eager to take freedom’s ride. Wisely, they are paying no heed to those who wish to speak to them of liberty’s risks.

Fouad Ajami, a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, is the author of “The Foreigner’s Gift: The Americans, the Arabs and the Iraqis in Iraq.”

Down